LOS ANGELES — Run! Do not walk, run! To UCLA’s Fowler Museum for a show that will shock you with brilliance and reward you with joy.

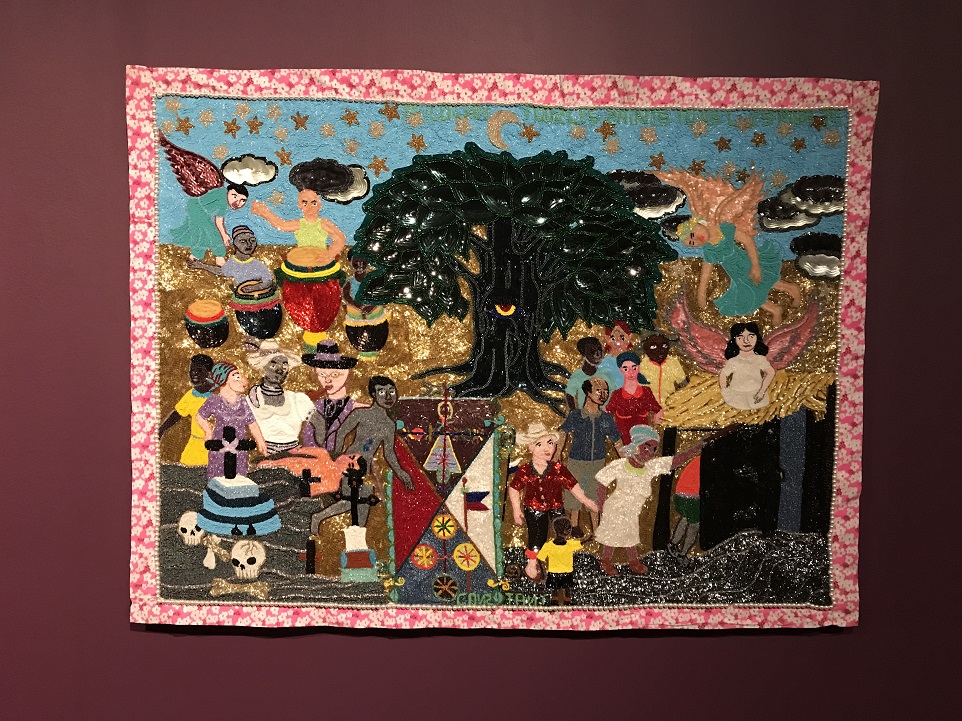

The Work of Radiance is a retrospective of the groundbreaking 30-year-long career of Myrlande Constant, an artist renowned for her monumental, hand-beaded textiles. The first U.S. museum exhibition devoted to the work of a Haitian female contemporary artist, the presentation and its accompanying publication trace the evolution of Constant’s artistic vision, innovative techniques, and impact on art-making in Haiti and the contemporary art world.

Born in 1968, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and still resident there, Constant is to beads and sequins what Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros were to walls. Many of her beads are made of seeds. Drawing intimately on her complex Haitian Creole cultural and spiritual heritage, with its many strains of Indigenous, African, European and North American influences, Constant has created an astounding body of work that rises from her own particularity to universal proportions.

Constant’s painstakingly beaded tapestries build on the drapo Vodou tradition and depict Haitians, Catholic saints, and Vodou spirits in both vast and intimate scenes of Haitian history and everyday life. Drapo simply means a flag “on cloth,” from the French drapeau for “flag,” related to the English word “drape.” Constant refers to her works as “flags,” and variations on the Haitian flag often appear in her work.

“We must remember our heroes,” says Constant, “because they work for us. We must not forget them. Their blood flows in our veins.”

The fully illustrated monograph, itself the first on a Black Haitian woman, features essays by curators, artists, and cultural figures. Even if Constant never has another exhibition, the scholarly catalogue serves notice of her existence so that it can no longer be said that there are no Haitian women artists deserving of worldwide renown. The curators proclaim that this show in and of itself represents a “revolutionary change in the art historical narrative.”

Myrlande Constant: The Work of Radiance is organized by the Fowler Museum at UCLA and curated by Katherine Smith, Fowler curatorial and research associate of Haitian arts, and Jerry Philogene, associate professor of American Studies at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pa., who have been familiar with Constant’s work for a couple of decades. Both spoke at the March 25 opening reception. Sadly, the artist herself could not attend the vernissage as she was unable to get a U.S. visa in time.

The exhibition was several years in the making, complicated by Covid, of course, the parlous conditions in Haiti at present, and the increased cost of shipping that the panelists attributed to the war in Ukraine.

Smith and Philogene spoke in some detail about the artist, who was assuredly an unknown quantity to most opening night visitors. They referred to Constant’s own assessment that her work is “painting with beads,” and there is much truth to this concept. From a distance, and in many cases even from up close, the mind’s eye often fails to discern the teeny, tiny individual beads that make up her canvases. Every bead on the panel required two stitches of labor.

In earlier life, Myrlande was living with her family in the Haitian countryside, but over time, along with many others, they relocated to the city for work. Her mother and she both took a job in a shop that made wedding dresses, which often featured beaded decoration. Myrlande took the technical knowledge from this unconventional training and propelled it into high art. She now supervises her Martissant Atelier, a workshop employing several young workers whom she has taught the process. They work on a framed cloth panel on which Constant has drawn her intricate design. And she is a strict teacher with a high work ethic and standard: If the work is not to her satisfaction, she thinks nothing of unraveling it all.

Given the range of themes appearing in Constant’s art, the scholars made an important point: that this body of work is not to be considered only as a limited Haitian national expression, but as art of the African diaspora.

Constant has visited the United States many times. She has family members living her, and she also comes to purchase art supplies that are unavailable in Haiti. She has often been asked if she wouldn’t be happier living and working in the U.S., especially now that the regime in her country is so violent and anarchic. But no, she prefers her own country, and somehow has found a way to thrive and continue making her art, with the protective spirits of her ancestors all around her. She can set her own schedule as she wishes and not have to answer to other people’s deadlines.

Artists working in non-traditional mediums can often be labeled “self-taught,” but the curators believe this demeans the work itself as “naïve” or “outsider” art. In Constant’s case, they say, she is not “self-taught”: Fashioning élite wedding dresses, she was “trained in the underbelly of capitalism.” Constant is now represented by a New York gallery.

With rich opportunities opening up for her at this stage of her career, Constant has to consider how she wants to live. If she makes any money from sales of her work, she turns that back into pay for more workers she’s able to hire for her atelier. (And incidentally, the idea of an atelier is an old system where hired workers of master artists—call them protégés or apprentices or students, if you will—were given the chores of painting clouds, skies, foliage or lacework while the master concentrated on the main subject, such as a portrait.)

And she can live with the poetic, epigrammatic parables with which she peppers her conversation. One Haitian proverb the curators cited, for example, can stand in for a whole speaking style, while also underlining the artist’s own modesty: “With patience,” Constant says, “you can be the nipple of an ant.”

“I have had a good career alongside my team of workers and supporters,” Constant says in an Artist’s Statement. “In my society, it is not easy for a woman to have a dream and realize it. Society has rules for men and women. Women are supposed to stay in the house, and take care of the household. But my husband, like many men in Haiti, has not worked in a long time. So, I play both roles. I support my household and they support me in my creativity. To realize my dream requires a lot of patience and time—and women don’t often get the time to be creative.”

The Work of Radiance is on view through July 16, 2023. The Fowler Museum is located on the UCLA campus, 308 Charles E. Young Dr. N, Los Angeles 90095. Visiting hours are Weds.-Sun., 12-5 pm. Admission is free.

In connection with the Constant exhibition, special programming has been scheduled. On Sat., April 8, from 6-9 pm, is Fowler Films: Celebration of Haitian Art. On Fri., May 12, from 9 am to 5 pm is A Symposium on the Art of Myrlande Constant. And on Sat., May 20, from 12-2 pm, is Creativity in the Courtyard: The Work of Radiance. To reserve for programs, visit fowler.ucla.edu/programs.

We hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, please support great working-class and pro-people journalism by donating to People’s World.

We are not neutral. Our mission is to be a voice for truth, democracy, the environment, and socialism. We believe in people before profits. So, we take sides. Yours!

We are part of the pro-democracy media contesting the vast right-wing media propaganda ecosystem brainwashing tens of millions and putting democracy at risk.

Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader supported. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all.

But we need your help. It takes money—a lot of it—to produce and cover unique stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today.