The best kind of vampire films understand that there are worse things in society than blood-sucking monsters with fangs. The horror genre has often been a cinematic landscape exploring themes in our world that aren’t the most pleasant. When movies in this genre lean into this legacy with bold, imaginative storytelling, the result can often be compelling original stories that lure us in with terror and keep us captivated with the very human condition at the heart of it all.

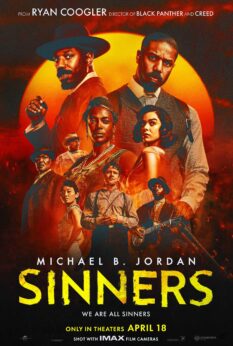

Ryan Coogler’s latest film, Sinners, achieves such a feat. Carrying on the legacy of impactful vampire classics before it, such as Nosferatu (1922), the film combines horror, history, blues music, and Black American folklore for a thrilling journey into darkness, of both the supernatural and everyday varieties.

Written, co-produced, and directed by Coogler, Sinners is set in the 1932 Mississippi Delta. It follows twin brothers Smoke and Stack (both played by Michael B. Jordan), who have returned to Clarksdale, Miss., after years spent working in the world of organized crime in Chicago. The brothers, World War I veterans, have a younger cousin, Sammie, who’s an aspiring Blues singer.

Written, co-produced, and directed by Coogler, Sinners is set in the 1932 Mississippi Delta. It follows twin brothers Smoke and Stack (both played by Michael B. Jordan), who have returned to Clarksdale, Miss., after years spent working in the world of organized crime in Chicago. The brothers, World War I veterans, have a younger cousin, Sammie, who’s an aspiring Blues singer.

Though they accumulated it under mysterious circumstances, the brothers put together enough cash to purchase a sawmill from a racist landowner. Their plan: Start a juke joint for the local Black community, but opening night at the club is when the terror begins. Leading an attack by a pack of bloodsuckers is an Irish vampire named Remmick, who’s set on turning the three against each other. He explicitly sets his sights on Sammie because of the power his music unleashes.

There’s no doubt that Sinners is an ambitious and original supernatural tale. Yet, what makes it most unique is that it is steeped in real history, interweaving the Black American experience of the early 1900s and the origins of song and dance throughout multiple cultures, specifically Black, Chinese, and Irish. The film encompasses numerous themes, even if it doesn’t delve deeply into all of them. The acknowledgment is there, though, tempting filmgoers to find out more on their own.

It’s important to understand the historical backdrop of Sinners, particularly because of the way it determines the wants, desires, and fears of our main characters.

Smoke and Stack are veterans at a time in history with a unique set of racial complexities. While it’s said there were many Black men who eagerly enlisted in the military when Uncle Sam issued the call during the First World War, many others faced an onslaught of discriminatory conscription practices. Predominantly white draft boards, for instance, targeted Black men for war at higher rates than whites. And while comprising just 10% of the entire United States population, Black people supplied 13% of inductees.

By 1932, the Great Depression was in full swing. While the economic collapse affected working people of all ethnicities, it was an extremely challenging period for Black Americans, as they faced high unemployment, discrimination, and increased racial violence all at the same time. Lynchings by the white supremacist domestic terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan were on the rise. Black people were often the first to be laid off from their jobs, suffering from an unemployment rate two to three times that of their white counterparts.

These challenges factored into what has come to be known as the Great Migration, the time period when large numbers of Black people migrated from the South to urban areas in the North and West seeking better economic opportunities.

Yet, despite what far too often sanitized mainstream history would have us believe, the North was not some racially enlightened region immune to inequality and discrimination. While racism may not have always been as overt as in the South, Black people faced discrimination there as well.

This is the world the twins and Sammie find themselves in. It’s clear that Stack and Smoke have turned to their less-than-lawful lives due to the cards society has dealt them. Jordan brings layers to both brothers in an interesting and compelling way that makes them distinctive and believable. There is talk of power and freedom in the film, but it’s clear there is an understanding by the brothers that playing by society’s rules for Black people won’t get them far in life. This grey area when it comes to morality is a prevalent theme in the movie—it’s called Sinners, after all.

The character of Sammie is where the role of Christianity in the Black community is explored. His father is a local preacher, unapproving of Sammie’s desire to play blues. His father wants him to follow in his footsteps and become a pastor, preaching the gospel. Sammie, played by newcomer Miles Caton, feels like he has another calling with his music, however, and looks to a future beyond sharecropping and small-town country life. As he follows his older cousins around for the day and night (before the blood starts to run), the young man is introduced to concepts that challenge his father’s teachings.

A particularly poignant moment occurs when Sammie is talking to pianist Delta Sim (played to comedic and dramatic perfection by Delroy Lindo), who asserts to Sammie that while Christianity was pushed on Black people when they came to America, blues music originates in Black people’s souls. It’s what they brought here with them that no one can take away. The power that music has on culture, in some cases being a form of resistance, is prevalent throughout the film as both heroes and villains alike express themselves through it.

Another aspect of Black spirituality is explored through the character of Annie (Wunmi Mosaku), who is a Hoodoo practitioner and Smoke’s girlfriend. Hoodoo is an African-American spiritual tradition that uses conjure and rootwork. Developed from various African diaspora religions, it focuses on listening to and interacting with the Black ancestors for guidance.

This was a much-welcomed addition to the story because this aspect of Black spirituality isn’t often highlighted in mainstream entertainment. When it comes to displays of African-American spirituality on screen, it often occurs within the rigid confines of Christianity or a caricaturized version of voodoo (for some reason, even though voodoo is primarily associated with Haiti).

And in highlighting Mosaku’s captivating performance, a special shoutout needs to be handed to the other women leads who all portray layered and passionate characters, not solely defined by whichever romantic partners they have, but by their own drives and desires. Hailee Steinfeld, Jayme Lawson, and Li Jun Li each hold their own on screen, exemplifying just how talented the entire ensemble is.

The music of the film feels like a character all its own, guiding the viewer through the rollercoaster of happenings as Sinners carries on. The original score, composed by Ludwig Göransson, accentuates every moment, being an essential part of the sensory immersion the film provides. The song and dances by the cast, meanwhile, bring a fresh element to the storytelling experience.

Interestingly enough, while this is a vampire movie, the actual vampire happenings don’t feel like the most prominent aspect of Sinners. Coogler has the audience spend plenty of time with the main cast of characters before any fangs descend. We get to know the trials and tribulations of the twins, Sammie, and other characters in their lives before the supernatural elements really take off. It’s not necessarily a slow burn but rather a proper building of a storytelling foundation to make the stakes higher when danger appears. Sinners has plenty of action, blood, and gore, but it is predominantly character-driven.

There have been comparisons between the movie and more recent vampire films, such as Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino’s From Dusk till Dawn (1996). While that movie is action-packed fun with a set of brothers and some vampires trying to get into a bar, the comparisons really should stop there. This critic would argue that Sinners has more in common with Nosferatu (1922) than the previously mentioned vampire romper.

That’s because just as Nosferatu explored themes like politics, plagues, xenophobia, and sexual repression that still strike a heavy chord in our current moment, Sinners tackles religion, spirituality, racism, and repression with just as much nuance and vigor.

The Irish vampire leader Remmick (with a standout performance by Jack O’Connell) also serves as the “other,” just as Count Orlok did. Bonus points to Sinners for connecting the very comparable struggle of the people of Ireland to those of Black Americans. The oppression of the Irish people carried out by the British Empire spanned centuries, involving political, economic, and social persecution that deeply impacted them, bringing about widespread poverty, famine, and emigration. It’s made clear in the film that Coogler’s choice of Remmick’s background is deliberate and just as important when it comes to his interactions with the other characters.

What is certain is that original storytelling like Coogler’s needs to be a more common occurrence in theater experiences. For Sinners to get a wide theatrical release by a major studio when it is not connected to a comic book or any other already established IP is no small feat in risk- (and diversity-) adverse Hollywood.

It is a must-see film that has plenty to say and which will have audiences talking about it long after the credits roll (and do be sure to sit through the credits as there is a bonus scene that manages to hold an emotional punch). It features a predominantly Black cast and a story that doesn’t shy away from history at a time when certain powers that be are dead-set on erasing it. It is an instant classic that will no doubt be dissected and analyzed for years to come, rightly so.