With ceasefire negotiations between Ukraine and Russia underway in Turkey, even as the fighting continues in the east, retired People’s World Editor Tim Wheeler shares his memories of visiting Kiev in 1974. At the time, the city was the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union.

I will never forget where I was on April 12, 1974. My late wife Joyce and I were stepping into a crowded elevator in an elegant hotel on Khreshatyk Street in Kiev, Ukrainian SSR. The elevator was packed with bright-eyed teenagers. One of them spoke to another in unmistakably American English.

“Oh, you’re from the United States,” Joyce exclaimed. “So are we.”

They all nodded and in unison replied that yes, they were.

One of them explained that they were Harvard undergraduate students. They had been on an extended field trip traveling all over the Soviet Union for the past month, practicing their Russian but still feeling isolated, starved for news from the United States.

“We’re delighted to run into you. What’s new back home?” inquired a sophomore from Wisconsin.

I racked my brain trying to think of something other than the latest grim news about the Watergate hearings. “Oh yes,” I replied. “Hank Aaron just broke Babe Ruth’s home run record.”

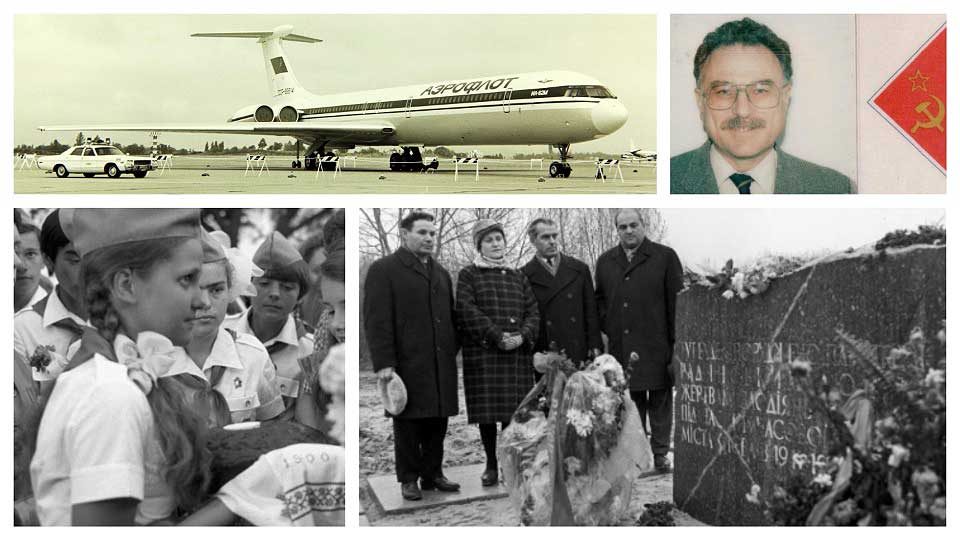

A cheer erupted from all of them, and this moment became fixed in my mind, never to be forgotten, and probably fixed in their memories as well. It eclipsed other memories of that trip hosted by the Soviet airline, Aeroflot, celebrating the inauguration of joint flights between Washington’s Dulles Airport and Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport by Pan American Airways and Aeroflot.

In honor of this victory for U.S.-Soviet détente, Aeroflot invited a large delegation of Nixon administration officials led by Transportation Secretary Claude Brinegar, whose main claim to fame was that he had been the CEO of Sun Oil Company.

Also in the delegation was astronaut Joe Kerwin, who had recently flown over the USSR aboard NASA’s Skylab and made graceful toasts to our Soviet hosts about admiring the Soviet Union and how we must have peace between our two countries. On the trip as well was a large delegation of Pan Am officials, including an African-American executive, Fred Royal.

The Soviet Embassy extended an invitation to the Daily World to send a reporter to cover the trip. I was assigned. But when I told Joyce that I was going to fly all-expenses paid on a whirlwind trip to Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev, she replied, “What about me?”

I called Alexander Evstafiev, First Secretary of the Soviet Embassy. In so many words, I said, “Sasha, Comrade, Joyce was delighted to hear that I am traveling to the Soviet Union. Her immediate response was: ‘What about me?’ Any chance she can go too?”

Evstafiev told me he would get back to me. That afternoon, he called. “Yes, Joyce is welcome to come, too.”

And now that my poor old brain is stirred by Hank Aaron’s prowess at the bat, what other memories do I have of the USSR? Probably the most touching was the hospitality of the Ukrainians in hosting us. When we stepped down from the Aeroflot plane at the Kiev airport, we were greeted by a line of Ukrainian women dressed in colorful peasant dresses holding out freshly baked bread and handfuls of salt to welcome us. A balalaika ensemble played Russian and Ukrainian folk songs to greet us.

Our interpreter asked us if there was any place in Kiev we wanted to see. Joyce replied, “Yes. Please take us to Babi Yar if that can be arranged.” Sure enough, that afternoon, our interpreter picked us up and took Joyce and me in a cab to the long depression in a wooded park-like place on the outskirts of Kiev.

The interpreter explained to us that Babi Yar was being turned into an anti-war memorial to tens of thousands of Jews murdered by the Nazi occupiers, their bodies dumped into a trench, buried unmarked. The great Soviet poet, Yevgeny Yevtushenko—himself of Ukrainian descent—had written a poem, “Babi Yar,” that went viral in the Soviet Union and around the world against this mass execution. Joyce laid flowers at Babi Yar.

The same day we met those American students on the elevator, we were taken to a “Youth Palace” in Taras Shevshenko Park on the high bluff overlooking the Dnieper River. Nearby was the monument to the tens of thousands of Red Army soldiers who died in the defense of Kiev during World War II.

As we walked past this war monument, a young couple was placing flowers on the monument. Our interpreter whispered to us that this young couple was planning to get married, that every couple in the Soviet Union honors the memory of the war dead by placing flowers on war memorials to honor those who died defending their nation from the Nazi invaders.

In the Youth Palace, we were again greeted with fresh bread and salt, held out to us by Young Pioneers, each with a red scarf around his or her neck. A little girl held out bread and salt to Joyce. I saw tears welling in Joyce’s eyes. That was doubtless a moment fixed in Joyce’s mind. She was a lifelong elementary school teacher and loved every little munchkin as if she or he were her own.

These memories of my time with Joyce visiting the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic more than a half-century ago feel bittersweet, given the years of brutal combat that have been visited on this country as of late.

We need to end this war! Too many Ukrainians have died, and too many Russians, too. So many children like that little girl holding out bread to Joyce and me have seen their futures sacrificed in the fires of war. No more.

As with all op-eds published by People’s World, the views reflected here are those of the author.