The 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as COP30, which took place from November 10–21, 2025, in Belém, Brazil, ended recently with no mention of the fossil fuels that have warmed up the atmosphere. The final deal also failed to include any further commitment to limit deforestation.

COP30 kicked off this year with the glaring absence of an official delegation from the United States. Donald Trump decided in January to abandon international cooperation on global warming, even though the United States is the largest historical emitter of greenhouse gases and continues to be one of the greatest emitters today.

Global South nations, notably in Latin America, acted as strong leaders in the Conference, with urgent calls for a fossil fuel phase-out coming from Brazil, Colombia, and members of the Alliance of Small Island States (Aosis), including Cuba, Vanuatu, and the Bahamas.

The two-week conference ended in almost total failure, with a large majority of nations unsatisfied with the final agreement. Despite major debates and public pressure, the mitigation work plan included no direct mention of the fossil fuels that drive climate change, and the global goal on adaptation remains incoherent.

Many nations represented at this year’s COP, including some of the world’s most vulnerable to climate change, had called for the deal to include a roadmap to explicitly phase out fossil fuels. But, any agreement on a phase-out plan was killed by the coalition of oil-producing states, including Saudi Arabia and Russia, as well as some growing economies like China and India.

Michael Jacobs, Senior Fellow at ODI Global, told Reuters that “after the gavel has come down, so when the decision has been made, lots and lots of countries getting up to say that they are deeply dissatisfied with it. Indeed, some are saying that it is illegitimate… So there’s a lot of anger at the outcome.”

A more positive outcome of COP30 was the agreement to triple the funds destined for adaptation finance by 2035. These are funds promised to help the most vulnerable nations, often poorer and less developed nations, adapt to climate threats. However, the finance plan will take an extra five years from previous agreements to go into full effect and includes vague language that has raised concerns. Adaptation funds are an important lever of climate justice, acknowledging that the nations most affected by climate change are often those least responsible for causing it.

As Colombian Environmental Minister Irene Vélez Torres told reporters, “Clearly, the oil-producing countries are only trying to focus on adaptation. But adaptation is an empty bag if mitigation doesn’t come next to adaptation. Adaptation alone and the finances for adaptation are not sufficient if we do not deal with the problem. The root cause of this problem is fossil fuels.”

Fossil Fuel Lobby runs the show

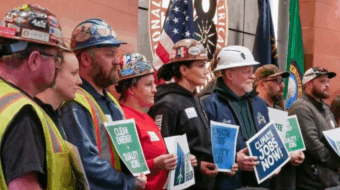

Environmental justice advocates and Indigenous activists lambasted the conference over the large presence of fossil fuel representatives in participation.

According to a report by the Kick Big Polluters Out (KBPO) coalition, more than 1,600 lobbyists linked to the oil, gas, and coal industries were accredited to COP30. This means that one in every 25 participants was linked to the fossil fuel sector.

This figure represents a 12 percent increase compared to last year’s summit in Baku, according to the same analysis. Over the last five COPs, the KBPO estimates that nearly 7,000 people linked to fossil fuels have participated in the discussions.

Major energy companies such as ExxonMobil, BP, and TotalEnergies were represented, often through industry groups. Even more alarmingly, some fossil fuel executives are even part of official national delegations. For example, France had 22 delegates linked to the fossil fuel industry, including senior executives from TotalEnergies.

Even worse, transparency advocates sound the alarms over the potential for undisclosed conflicts of interest among delegation members since more than half have withheld or obscured details of their affiliations.

The fossil fuel industry, which has a long history of spreading misinformation and disinformation while blocking meaningful climate action, received almost 60 percent more passes to COP30 than the 10 most climate-vulnerable nations combined (1,061).

Indigenous leaders speak out

Even though little could be said to have been achieved, COP30 remains one of the only arenas through which many environmentalists, but especially Indigenous communities, can struggle to raise awareness of the existential issues they face and wish to tackle head-on.

Amanda Pankará, from the Pankará people in Pernambuco, told UN News that COP30 provides a space where Indigenous issues can gain greater visibility. “We would have much more to contribute if more Indigenous people were participating in these discussions. These demands are valid. We are claiming the right to land, the right to life… We are the ones who create this protective barrier, so we want to be heard.”

Saturday, November 15, tens of thousands of people took to the streets of the host city, Belém, to demand urgent climate action. The Indigenous-led action brought together demonstrators denouncing corporate greed, war, and imperialism, and demanding urgent action to reduce the use of fossil fuels and to respect Indigenous sovereignty.

“Today we are witnessing a massacre as our forest is being destroyed,” said Benedito Huni Kuin, a 50-year-old member of the Huni Kuin Indigenous group from western Brazil.

“We want to make our voices heard from the Amazon and demand results,” he added. “We need more Indigenous representatives at COP to defend our rights.” Their demands include reparations for damages caused by corporations and governments, particularly to marginalized communities.

The night before, an Indigenous-led march arrived at the perimeter of the COP’s “Blue Zone,” a secure area accessible only to those bearing official summit credentials. The group stormed security, kicking down a door before the United Nations police contained the protest.

“They needed to listen to us… So we blocked entry to COP because we need to be heard,” said Alessandra Korap Munduruku, who in 2023 was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for her leadership in resistance organizing that led the British multinational mining company Anglo American to withdraw from Indigenous lands, including those of the Munduruku Indigenous group of Sawré Muybu in Brazil of which she is a member.

In an extended interview with Democracy Now! she stressed the marginalization of Indigenous voices who “live in the Amazon forest” from decisions taken at COP.

“We know what the river is going through. We need the river. We live with the river. Today, the river, the Tapajós River, is dry. There are days in which the river disappears. There are so many forest fires. So, why is it that we cannot have the power to decide here at COP? Why is it that they only speak about us, but that we cannot decide?” asked the environmental activist.

“The rivers, the Tapajós River, the Madeira River, they are being privatized for the creation of hydro waste, for the transportation of soy for agribusiness. This will expand the production of soy in Brazil. It will lead to more deforestation. It will lead to more Indigenous rights violations,” she added.

AI: climate friend or foe?

Another controversy at this year’s COP was over the role of artificial intelligence. Corporate lobbyists representing Google, Nvidia, and other firms attended the gathering, hawking AI products and software as solutions to climate concerns. During at least two dozen sessions related to AI, promoters’ promises ranged from the grandiose to the mundane. Some say AI could be used to help optimize energy grids or assist in climate modeling and extreme weather early warning systems.

Nvidia’s head of sustainability, Josh Parker, was more extreme. He claimed that AI could be useful for just about anything, an indispensable tool in the fight against climate change.

While tech companies tried to sell artificial intelligence as a sustainability tool, they were notably silent on the enormous environmental damage caused by AI today. Jean Su, the Energy Justice Director of the Center for Biological Diversity, notes the enormous amount of energy consumed by data centers for AI computing and warns that the vast majority of these energy needs are met by fracked gas.

The majority of data center computing and construction worldwide occurs in the United States, where Donald Trump’s policy has been to double down on fossil fuel production to supply its vast energy needs. In response to the claims on AI’s potential uses to help combat climate change, Su stated: “I think the future can include the AI that actually benefits the public interest. However, that is a foil and a red herring for the vast majority of AI right now, which is actually being used on defense and militarization, things that do not benefit the public interest.”

“What we need to do,” she continued, “is empower communities and countries, especially in the Global South, to ask what is the public benefit that they are supposed to get from AI and weigh it very carefully against the severe costs to their climate, to their electricity prices, and to their water.”

Need to phase out fossil fuels

While the thirteenth COP meeting yielded a watered-down deal, weak on the core issue of fossil fuels, the governments of Colombia and the Netherlands announced they will co-host the First International Conference on the Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels in April 2026 in Colombia.

Per reporting by the Fossil Fuel Treaty Initiative, Maina Talia, Minister of Climate Change of Tuvalu, a Pacific Island nation facing the existential threat of rising sea levels, affirmed that “We must ensure that any transition is rooted in equity and justice, empowering nations like Tuvalu to adapt and thrive in the face of unprecedented challenges. We are committed to working with all stakeholders, and bringing more countries from all regions to the table, to forge a treaty that reflects the urgency and scale of the climate emergency, and secures a viable future for our people and our culture.”

Ultimately, the fragile and weak agreement coming out of COP30 is indicative of the stark divisions and inequality between the nations most vulnerable and those most responsible for climate change. It also highlights the power and influence of the fossil fuel lobby and other corporate polluters, who do everything in their power to stymie real solutions and the transformative change the world needs to avoid the worst-case scenarios of global warming.

While the U.S. boycotts COP and powerful corporate forces seek to effectively undercut its potential, Global South countries, Indigenous peoples, peasant coalitions, and other mass people’s movements continue to lead the world in demanding and organizing for a global just transition.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today.