The early prospect of a new constitution to replace Cuba’s current one, in effect since 1976, begs the question of how it might serve the Cuban revolution. In particular, will the new fundamental law help or hinder the cause of Cuban socialism?

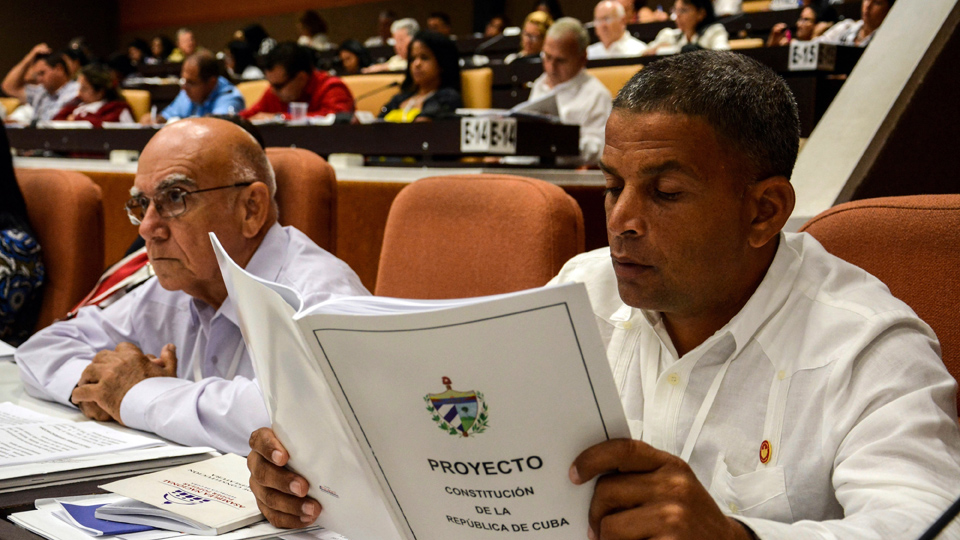

The process of changing the constitution began in 2013, but moved into high gear on June 2 when the National Assembly created a temporary commission of 33 experts for shaping a draft version. The Assembly approved that on July 22. The Cuban people will be discussing the revisions in community and work-place meetings between August 13 and November 15. The Assembly will then approve the resulting document and, next, the Cuban people will vote yes or no on the final package.

Information as to the reach of the proposed changes and the most significant proposals derives from Cuban media reports on three days of discussion in the Assembly. That’s because a print version of the draft constitution has not been available to the public or press but only to Assembly members.

The main proposals are these:

— According to Cubadebate.cu, the new constitution will “ratify the socialist character of the Revolution and retains “principles of social justice and humanism.” “The Communist Party maintains its role as the principal force leading the society and state.”

— The text emphasizes that “socialist property belonging to all the people is fundamental,” but it authorizes ownership of property by cooperatives, by mixed public-private and private entities, and by organizations.

— The draft constitution casts state enterprises as central to “generating the wealth of the country.” Also, the state’s role in controlling economic processes is paramount, limitations do remain on the concentration of property by non-state entities, and “foreign investment is a necessity and an important element of development.”

— In respect to private property in land: “its sale or transfer is subject to limitations set by legislation and to the preferential right of the state to acquire it.” The inheritance of private property in land will be respected.

— The revised constitution establishes the new office of prime minister who, nominated by the president and designated by the National Assembly for a five-year term, will direct governmental affairs through his or her leadership of the Council of Ministers.

— Cuba’s president, elected as before by the National Assembly and now limited to two five-year terms, will serve as chief of state and continue to preside over the Councils of State and of Ministers.

— Provincial assemblies will be abolished in favor of provincial governors—appointed by the National Assembly—and provincial councils. The latter will comprise presidents of municipal assemblies and “intendentes,” who lead the councils of municipal administration. These councils are new. The proposed constitution widens the autonomy of municipal assembles for the sake of “more rapid and efficient” action. A citizen’s right to petition municipal assemblies is guaranteed.

There is a vast sea of other constitutional revisions. Indeed, the re-worked constitution contains 224 articles, 87 more than does the present constitution. Eleven articles appearing in that one are preserved, 13 are eliminated, and 113 are altered.

The new instrument guarantees the right of same-sex marriage and contains new provisions for national defense, family and civil codes, election regulations, penal codes, environmental protection, and due process. It offers new backing for the rights of women and of transgender, disabled, and elderly citizens. Press and religious freedom are expanded, as is freedom of expression.

Altered government economic policies evolving over 10 years set the stage for constitutional change. The project is in response also to expanded concepts of human rights, to bureaucratic barriers to political and economic innovations, and to persistent and serious problems in making the economy work.

A big part of the story of Cuba’s new constitution is speculation as to its effect on the socialist and/or communist nature of Cuba’s politics. The New York Times, for instance, noted that the draft constitution is silent on “the goal of building a ‘communist society,’” which the current one mentions. Or as observed by the Times of London, “the Cuban government has given up its ambition of building a communist state.”

However, Cuba’s Granma newspaper, published by the Communist Party, did say in regard to the National Assembly deliberations that: “The Communist party of Cuba, the organized vanguard of the Cuban nation…is the superior and leading force for society and the state as it organizes and orients common efforts toward the lofty purposes of building socialism and moving toward a communist society.”

Other concerns are about the future of Cuban socialism. One observer of the proceedings, for example, diagnoses a failure to distinguish accumulation of wealth from concentration of wealth, which may be easier to limit. He cites an exchange between deputies. One sees danger in private property. The other points out that wealth concentration depends on property concentration, so the state should focus on limiting that.

A commentator recalls that “in the Soviet Union socialism fell because [at some point] market mechanisms developed that ate away at the material base for socialism.”

According to alainet.org, however, “The socialist property of all the people will continue to be the nucleus of the political and economic system, and the adjustments to the constitution serve [merely] to give constitutional standing to already existing recognition of private property in the country.”

Speaking to the Assembly, Homero Acosta, secretary of Cuba’s Council of State, maintained that, according to the draft constitution, the state will be able forcibly to expropriate private property for reasons of “public utility or social interest, with payments and guarantees that are due.” And the state “directs, regulates, and controls economic activity in line with overall planning that is the central element of its leadership role in economic development.”

In the end, those who see constitutional changes as a way station to capitalist revival in Cuba might ponder on realities pressing upon Cuba. They threaten the survival of its revolution. One of the revolution’s consistent themes, from the time of wars for independence from Spain, has been independence from U.S. pretentions and meddling. They pose one threat. Economic troubles are another.

At the National Assembly meeting under discussion here, deputies learned that during the first half of 2018, economic growth was a low 1.1 percent. Cuba’s government is dealing with mountains of unpaid debt owed to foreign creditors. The necessity to pay well over $2 billion annually for imported food products has been constant. There’s no sign that the U.S. trade and financial blockade and other interventions are disappearing soon.

That may be why President Miguel Díaz-Canel chose these words to close the July 22 National Assembly session on the constitution:

“[T]he principal obstacle to our development is the [economic] blockade”—imposed by the United States.

Another part of the context is that Cuban authorities are aware that a “third way”—political centrism between socialism and capitalism—has gained currency on the island. Thus consideration of constitutional change takes place within a highly unstable setting.

Law professor and National Assembly deputy José L. Toledo Santander recently reviewed Cuba’s long history of introducing new constitutions. They’ve often been in response to societal upheavals and for the sake of national independence. He implies that the two-fold purpose of the new constitution is preservation of Cuba’s revolution and as an assist to solving problems. To be effective in this regard, it must promote unity among the Cuban people. Indeed, President Diaz-Canel speaking to the National Assembly indicated that the “project [is] aimed at strengthening the unity of Cubans around the Revolution.”

Toledo Santander predicts, in regard to the constitution, that: “Given Cubans’ commitment to our historical legacy, with so many years of struggle to preserve our independence and sovereignty…and recalling Marti’s convictions, we are more aware than ever, as he taught us, that the sun has spots, but that the grateful see its light, and in this battle we will be united like a vein of silver in the Andes, and will fulfill our civic duty to reaffirm a revolutionary, socialist homeland, ‘with all and for the good of all’”—as per José Martí.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.