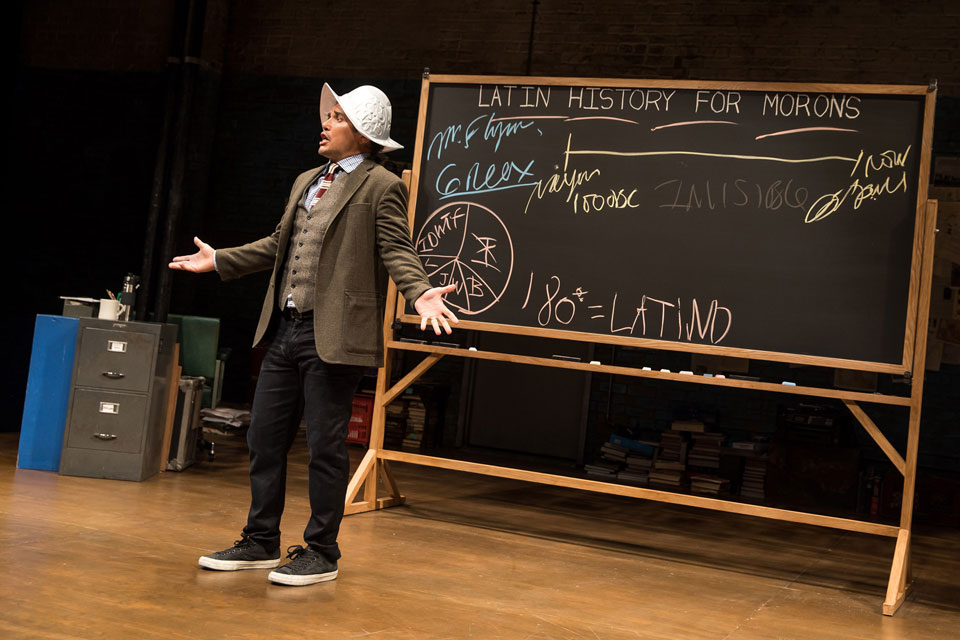

LOS ANGELES—Who are the “morons,” one might ask, for whom John Leguizamo’s one-man show is meant to play? “That’s you,” the actor asserts, pointing out to his audience classroom. But it equally applies to all those people, including himself and his children, who never knew their heroes, were never taught about them in school—whole history textbooks with nary a mention of Latinx in America—and never saw them represented in the media. It was the great disappearing act of Latin history.

And yet, he says, “Latin history is American history.”

How are young Latinx kids supposed to grow up with heroes they admire and look up to when there’s not a single picture of anyone in their history books who looks like them? Who could blame them for feeling like second-class citizens?

As for the rest of us morons out there who are not Latinx, well, this show is also for us, so we start to understand where all this racist white supremacist chauvinism is coming from, and how it infects our brains.

Prompted by incidents of racial discrimination against his own son at a private school where he and his wife believed he would be shielded from such abuse, Leguizamo embarked on what would turn out to be a five-year evolution of the piece that’s now holding the stage at the Ahmanson Theater in downtown L.A. “I started doing a lot of research, and the thing that happened was I was the one being un-moronized and de-stupified and un-dummificated.”

May the un-moronization spread quickly like a prairie fire across the land. We need it!

Over that gestational period much has changed, most notably since Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign with a mean-spirited xenophobic broadside against Mexicans and immigrants that has only intensified since his assumption of office. “I feel like right now [the play is] at its most powerful, in a strange way,” the author says in a program note. “This administration, the worse it gets, the more impactful my play becomes, which is kind of a sad irony…. It makes me feel like I’m doing a public service by giving people hope that we can overcome all this, and that unity is better than division.”

Leguizamo, star of TV, film, and stage, is a well known master of genres that include straight acting, dance, hip-hop, stand-up, mimicry, mime and much more. He incorporates his ghetto-born mischievous bad-boy image into almost everything he does. From the clown of the inner-city classroom he has become, in this iteration, the theatrical Pagliacci of Broadway—a raunchy, rowdy, rude and crude comic putting on a happy face to mask his internal pain. All these aspects of the actor’s talent have been shaped and exploited to maximum effect by director Tony Taccone.

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect from this show—which won a Tony on Broadway, by the way. Would we be hearing mostly about iconic soccer and baseball players, and popular actors and singers? Would it possibly include thumbnail accounts of the great revolutions in Latin America—the Haitian, the Cuban, and the Mexican? Would we hear about the ongoing colonization of Puerto Rico, which the imperialist U.S. snatched from Spain in 1898 and never set free? Would we get familiarized with political personalities such as Benito Juárez, Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, José Martí, Salvador Allende, Hugo Chávez, Lula da Silva, Evo Morales and José Mujica, great women such as Berta Cáceres, Vilma Espín and Haydée Santamaría, with writers such as Pablo Neruda and Gabriel García Márquez, or scientists like Santos Dumont and Carlos Finlay?

No, most of those names and topics go relatively untouched. Leguizamo makes a more epic panorama of Western Hemisphere history.

He ticks off the many foods that came from the Americas—ever heard of corn, potatoes, tomatoes, chocolate, beans, quinoa? Fachrissake, what did those benighted Europeans eat before they sailed west? And in exchange we got deadly diseases from Europe, which he also ticks off one by one, and believe me, they’re not pretty. And then, as if we didn’t give enough to the world, how about all those dances—and he does a quick 60-second survey of half a dozen of the principal dance genres performed to a T to a lively soundtrack.

In his global overview, the playwright lays heavy emphasis on Indigenous roots of Latinx culture, with extended apostrophes to the gentle Taíno peoples whom Columbus encountered in the Caribbean (he never set foot on the continental mainland), and to the mighty Aztec and socialistic Inca empires, which fell not by the overwhelming sagacity of the conquistadors, nor by their overpowering arms, and certainly not by their professed Christian faith—the narrative of white superiority—but primarily, and tragically, by the diseases that wiped out some 95% of the original Western Hemisphere population of an estimated 73 million within a generation. This was ethnocide, or to use more familiar 20th-century words, pure genocide, a “Caribbean holocaust.”

“We were conquested—like me discovering your wallet in your back pocket and now it’s mine.” Native empires were also defeated by one of the great human frailties: NSD. That would be the narcissism of small differences, whereby the Spaniards exploited regional and tribal rivalries within those empires to split the resistance against the invaders. Of course, the Native peoples hadn’t the faintest idea what monumental global forces were now amassing on their pristine shores.

Among the many characters that Leguizamo embodies is his unctuous psychotherapist who, before “our time is up” (classic joke), manages to hear anger from his client over Unconscious Conquest Resentment that is indelibly part of Leguizamo’s personal complex of “issues.” Perhaps UCR can be extrapolated to the Latinx character in general, though generally undiagnosed as such. This was, after all, “the biggest theft in all of history.”

It was hard to completely avoid contemporary references. Cages for Indigenous people? “Don’t get me started,” the actor says. Still, he can’t resist observing that “Columbus was the Donald Trump of the New World.”

I don’t think I heard the actor enunciate the Mexican concept of “la Raza cósmica,” but he did illustrate it graphically, making productive use of the enormous blackboard on the set. This raza is not “race” as such, but the unique cultural mezcla, the mixing and combining of genetic material from many continents that makes up the general population. The global “cosmic” approach is perhaps best advised not only for Latinx audiences but for more general ones too. This history has been kept from us, but most people can relate in some form to the theme of displacement and migration. “How did we become so nonexistent?” he asks.

Being a history lesson as it is, Leguizamo asks for response from his class. What did the famous 19th-century American writer and editor Horace Greeley advise his readers, he asks. Many informed voices from this California audience correctly answered, “Go west, young man.” But what is the true meaning of that dictum, according to Leguizamo? Little else than crooks, murderers, and criminal exterminators pushing Manifest Destiny all the way out to the Pacific and beyond. Except that in our books and national mythology they’re called “pioneers,” right?

The conquistadors were mesmerized by gold and other precious metals and gems. When they found golden masterpieces of sculpture created by ancient Peruvian artisans, they simply melted them down into coins of the Spanish realm. The actor says it’s like an American couple visiting Florence and seeing Michelangelo’s David, and imagining that gorgeous marble put to much better use as a kitchen counter.

He wonders why what Latinx artists produce is considered “folk art,” while what European artists do is “fine art,” when actually, when you think about it, today’s modern art “is just our ‘folk art’ gentrified.”

Not all his history is so ancient. He speaks of the 1830 Indian Removal Act signed into law by President Andrew Jackson, and also of the way its centennial was celebrated in the 1930s by the Repatriation Act, whereby some 500,000 American citizens of Mexican heritage throughout the Southwest were summarily deported to Mexico. Despite protest against Trump’s proposals to discard the principle of “birthright” citizenship, it’s not like it would be for the first time! “Now they’re doing it again,” the playwright says, speculating that some Latinx may be attempting to deny their heritage out of self-protection. Yet 22% of the U.S. population is Latinx and growing.

Again, it’s a history lesson, so sources have to be cited. Leguizamo is generous with his credit toward those writers and books that opened his eyes, such as, foremost, Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. “This book saved my life.” He also favorably mentions the autobiographical story of Cuban Confederate soldier Loreta Janet Velásquez (although she was of course on the wrong side), Charles C. Mann’s books 1491 and 1493, about the New World before and after the cusp of European intervention, Eduardo Galeano’s books, and the magisterial work of scholar Jared Diamond in such works as Guns, Germs, and Steel. In the printed program he includes a very helpful four-page bibliography that he calls a “Required Reading List” categorized by “Baller Biographies,” “Our Indigenous Ancestors,” “The Real Latin History,” “We Write Too, Coño!” and “Extracurricular Reading,” in which more regional voices are featured.

In the end, what makes this a play, and not simply an entertainment from the high school or college history professor you never had but wish you did, is that Leguizamo structures it around his trying to reach through to his son (and marginally his daughter) about the dignity and richness of his paternal heritage (the mother is Jewish, so that’s a whole nother story.) In the acting out of his paternal, caring impulses, albeit in the clumsy, ineffectual way that “Dad” is now portrayed in our popular culture, this history lesson gradually catches up to you as a side-by-side coming of age story, not only for the kids but for the author himself as a now 50-year-old.

It also helps that Leguizamo doesn’t get everything quite right, the numbers don’t always add up, the facts are still a bit blurry, the spelling is off. It’s part of the bad-boy charm. This is a man on an urgent quixotic quest to study, learn, grow and teach, before it’s too late.

Aside from the trips to the shrink’s office, where he learns not only about his “latent ghetto rage” but also about the need to set aside all the clownish joking for a minute and listen to what’s really going on inside himself, Leguizamo exposes sensitive personal family history. The well-meaning but confused elders in the tribe, for example, or his gay brother who was thankfully not cured by conversion santería that their mother subjected him to, hilarious enactment of which we attend, natch.

The set (scenic design by Rachel Hauck) features the back brick wall of the theatre, the stage looking like an impromptu garage office, with the prominent central blackboard, a wide panel of posted notes and flyers, a desk, filing cabinets, chairs, piles of books, all looking messy and slightly professorial, but utilitarian: When the actor needs to reach for a prop to wear, or a book to hold up and show, he knows exactly where he’ll find it.

This one-man graphic novel/comic book physical/intellectual play puts “touché” on the expression “tour de force” (hey, French is a Latin language too).

Latin History for Morons plays through Oct. 20, with performances Weds. through Fri. at 8 p.m., Sat. at 2 and 8 p.m., and Sun. at 1 and 6:30 p.m., with several exceptions you can find at www.CenterTheatreGroup.org. Tickets can also be purchased by calling (213) 972-4400, or in person at the Center Theatre Group Box Office at The Music Center. The Ahmanson Theatre is located at 135 N. Grand Ave., L.A. 90012.