Root causes of the ongoing crisis in Venezuela are becoming increasingly apparent, as the situation in the country reaches a perilous state. Venezuela contains one-fifth of the planet’s known oil reserves, equal to the combined quantities of Iran and Iraq, leaving Saudi Arabia trailing in second place.

The United States’ fixation on Venezuela is directly due to the South American country’s near-bottomless resources, though one infrequently sees such a reality highlighted in establishment circles.

Should a figure sympathetic to American desires displace president Nicolás Maduro, control over Venezuela’s energy reserves would provide a tremendous boost to U.S. hegemony. It would help stem the superpower’s gradual and continuing decline.

U.S. imperialism has displayed expansionist ambitions for the past 196 years, dating to the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, named after then-president and Founding Father James Monroe. The Monroe Doctrine outlined the need to dislodge centuries-old European colonialism from the Americas, vast areas that successive U.S. leaders regarded as within their sphere.

Over the many decades since, America has pursued countless foreign interventions. As U.S. imperialism became increasingly powerful, its military attacks inflicted deepening misery and bloodshed, killing millions in Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq.

Such historical actualities appear to escape the attention of some mainstream analysts, who instead espouse America’s “traditional global leadership role” as that of a “shining democratic beacon” and “a paradigm worthy of emulation.” Instead, the focus is on how “Russians have been seeking to undermine U.S. democracy since 1945.”

The ruling class of the U.S. has, of course, hardly stood alone in wishing to spread its mastery to other continents, as many imperialist nations pursued a similar path before them. The seldom-mentioned occurrence is that, for those governing great powers, among the most important policies is gaining access to pivotal world regions and natural riches. Often distinctly low on their wish list is improving the living conditions of the masses.

This disdain for the welfare of general populations has been displayed by all imperial states over the past two millennia, from the Roman and Mongol dynasties to the French, Belgian, and German colonial empires.

The first instance of major U.S. imperialism was borne out under President James K. Polk in February 1848—when the U.S. military completed its capture of half of Mexico’s territory during a huge invasion, known most commonly as “the Mexican-American War.” This annexation of Mexican soil covered an area over five times the size of modern Germany.

The conflict lasted for almost two years, and its outcome shaped the borders that still exist to this day. Prior to the mid-1840s, Mexico had been larger in size than India, but following the U.S. assault, it was stripped of lands now known as California, Texas, Nevada, Utah, etc.

General and U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant described the attack on Mexico as “the most wicked war in history”. The American victory allowed them predominance over areas abundant in cotton, a commodity as prized in the 19th century as oil is today.

Thousands of miles away in the western Pacific, by the year 1902, the U.S. military had concluded its conquest of the Philippines, which was a bloody invasion executed on opportunistic grounds. Attaining a presence on the Filipino islands ensured the U.S. a prized base of operations in the planet’s largest ocean. It thereby enhanced U.S. power and prestige while dealing another blow to colonial Spain, whose subjugation of the Philippines dated to over 300 years before.

Moving into the post-1945 era, the U.S. has intervened in numerous states to varying degrees, overthrowing governments and erecting military dictatorships, if required, from Brazil and Argentina to Guatemala and Chile. The preferred strategy has been to back a dependable dictator that will (hopefully) do as told, rather than an unreliable democratically-elected leader that may seek to serve the people.

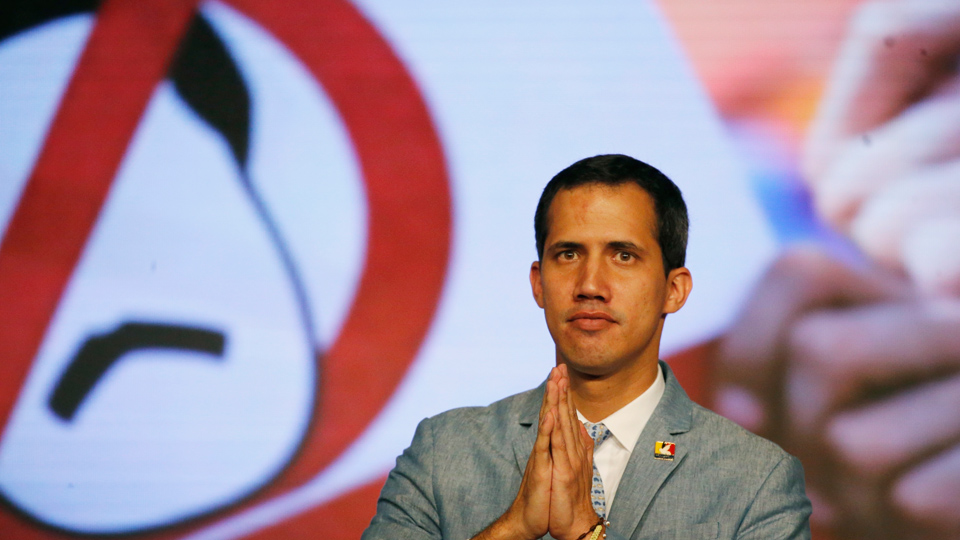

Currently in Venezuela, the colossus to the north is once more tightening its grip. President Donald Trump has spoken of his admiration for the “courageous” Venezuelan populace who have “demanded freedom and the rule of law.”

Trump, along with some Latin American and European states, has thrown his weight behind opposition leader Juan Guaidó. He’s a 35-year-old political newcomer clearly under the sway of Washington, having visited the U.S. just a few weeks ago and keeping in “regular contact” with the White House. During his youth, Guaidó received part of his tertiary education in Washington D.C., at the privately-run George Washington University.

One can cast aside Trump’s aspirations for “freedom and the rule of law” when witnessing his lasting support for governing elites like that of Saudi Arabia, an autocratic, medieval-style monarchy. Saudi Arabia has been ruled for decades by a succession of ruthless authoritarians yet enjoyed Western backing throughout.

In the meantime, while Venezuela is awash with oil, the country also contains the eighth largest gas reserves in the world. These are bolstered by extensive non-conventional oil deposits like tar sands (second only to Canada), bitumen, and extra-heavy crude oil, while also holding other substances like iron ore and coal.

U.S. involvement in Venezuela traces generations into the past and began increasing shortly after World War I when gigantic oil deposits were discovered about 300 miles west of its capital, Caracas. General Juan Vincente Gómez, a brutal and corrupt Venezuelan dictator—who held dominion for almost three decades until 1935—permitted U.S. companies like Standard Oil (today ExxonMobil) to write parts of Venezuela’s petroleum law.

For a decade from the late 1940s, Washington supported another Venezuelan strongman, General Marcos Pérez Jiménez. His was one of the most murderous dictatorships in Latin America, indiscriminately eliminating and torturing its opponents.

Unperturbed by Jiménez’ human rights abuses, in February 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded him the prestigious Legion of Merit decoration for “outstanding services to the Government of the United States.” Jiménez fled to America in early 1958 when overthrown by forces seeking something resembling democracy.

Over the past 20 years, with assumption of power by left-leaning figures—Hugo Chávez in 1999 and Maduro in 2013—U.S. influence over the mineral-rich state has been seriously hampered. Chávez, and then Maduro, have undoubtedly committed errors, like failing to shift the country away from its unfeasible reliance upon oil manufacturing.

At this late date, oil should surely be left where it belongs, in the ground, and its long exploitation has played a key part in driving up global carbon emissions. Ongoing widespread use of fossil fuels is unsustainable as climate change rapidly accelerates, threatening human civilization.

But much of the Venezuelan people’s hardships are, in fact, as a result of American pressures, such as an embargo, sanctions, and outright threats of invasion—none of which has received broad coverage in the mainstream media.