Christina Heatherton’s Arise! Global Radicalism in the Era of the Mexican Revolution is a massively important book about which so much needs to be said. It explores the centrality of the Mexican Revolution to the creation of a revolutionary internationalist political consciousness in the Americas in advance of and in conjunction with the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Heatherton organizes her work into six carefully sculpted chapters that map the growth and development of U.S.-based monopoly capitalism and imperialism and the transition of narrow, localized radical working-class politics into one with global aspirations and international relationships.

This crucial contribution to historical research on the study of internationalism deepens the work of previous writers such as Margaret Stevens’s Red International and Black Caribbean, Minkah Makalani’s In the Cause of Freedom: Radical Black Internationalism from Harlem to London, Winston James’s Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia, Jacob Zumoff’s The Communist International and U.S. Communism, 1919-1929, Roderick Bush’s The End of White World Supremacy, and Josephine Fowler’s Japanese and Chinese Immigrant Activists: Organizing in American and International Communist Movements, 1919-1933.

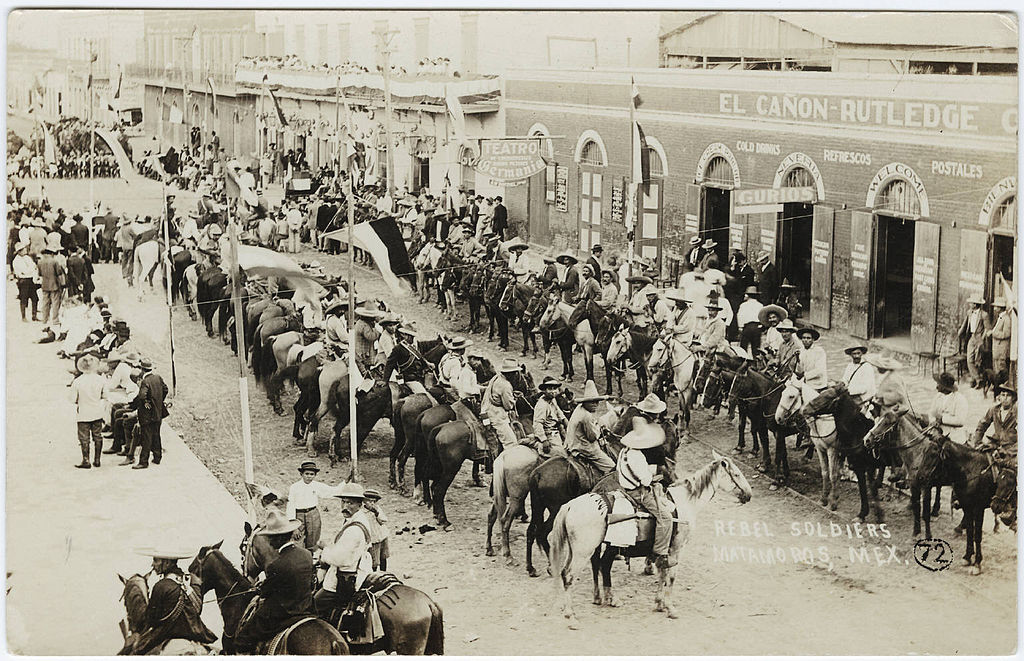

Chapter titles sharpen the focus on workers and work: “How to make a rope,” “How to make a dress,” and “How to make a living” are some of them. The opening two chapters—“How to make a rope” and “How to make a flag”—explore the development of U.S. imperialism, centering Mexico in that narrative. If monopoly capitalism, the basis of imperialism, develops as finance and industrial capital merge, massive private loans to the Mexican government by the Morgans, Du Ponts, and other U.S. capitalists helped to forge the creation of the National City Bank (Citibank), resulting in a situation where U.S. capitalists owned more than one-fifth of Mexico’s land and manipulated its national and local politics through what Heatherton calls “shadow hegemony.” Even prior to the U.S. entry onto the global imperialist stage during the 1898 war with Spain and its subsequent war of genocide in the Philippines, the U.S. capitalist class had been accumulating capital in Mexico that helped finance the second industrial revolution in the U.S. and poised it to become the major industrial-imperialist power after the First World War.

With carefully researched studies of major revolutionary figures such as the Mexican anarcho-syndicalist Ricardo Flores Magón, who was likely murdered by prison guards in Leavenworth prison in 1922, Heatherton shows how radical labor organizers such as Magón, Earl Browder, Ben Fletcher, Bill Haywood, and many other lesser-known Wobblies, anti-war protesters, socialists, and communists transformed the prison into a university of radical internationalism and organizing. Built by the prisoners of the U.S. government with forced labor, Leavenworth had become a tool of political repression of revolutionary action. Like Magón, many of the prisoners had their internationalist ideas forged by their work and lives in revolutionary Mexico before crossing the border to continue their revolutionary struggles in the U.S.

The Mexican Revolution fostered the political radicalization of many revolutionaries. M.N. Roy began his revolutionary life as an anti-British imperialism activist seeking to raise money for weapons to fight the British in India. He had first gone to California to create a network of supporters of the cause but fled to Mexico after political winds in the U.S., which had sold armaments to both sides in the First World War, shifted to align with the British. Roy turned to support for the Bolshevik revolution and became a leading figure in the Communist International in 1920. He authored the famous “Supplement to the Draft Thesis on the National and Colonial Question,” which modified Lenin’s contribution and elevated the anti-colonial struggles as a central pillar of the world communist movement’s strategic policy. Roy returned to Mexico and helped found the Mexican Communist Party.

When Communist Party leader and diplomat Alexandra Kollontai was appointed as the Soviet ambassador to Mexico in 1926, she came to a country still in the throes of revolutionary fervor. She was history’s first woman ambassador. In the book’s fourth chapter, “How to make love,” Heatherton uses Kollontai’s journey from the docks at Veracruz to Mexico City to tell a story through flashbacks of the diplomat’s experiences as a “Bolshevik feminist,” a revolutionary theorist of gender, family, birth control, romantic and sexual relationships, and her leadership role in shaping Soviet welfare policies. In addition, the narrative reveals the uprising of Mexico’s revolutionary struggle to wrest control of social institutions from the Catholic Church, to impose national sovereignty over its land and resources in the face of U.S. imperialism, and to elevate the power of Mexico’s workers and peasants through land reform, nationalization of key industries, and a nationwide program of secular public education. Targeted with false propaganda and conspiracies about her role in backing Mexico’s communists to infiltrate the U.S., Kollontai was forced to quietly leave her post in 1927.

The subsequent chapter is a study of the Communist Party’s role in organizing farm and industrial workers in Southern California along the U.S.-Mexico border and an account of the life and work of Communist Party artist Elizabeth Catlett in Mexico in the 1940s through the 1960s. Chapter 5, “How to make a living,” follows the work of Communist Party labor organizers like Dorothy Healey, Karl Yoneda, Elaine Black, Alfred Wagenknecht, Pettis Perry, and Adele Young who fought for relief for unemployed workers and for the right to organize for the multinational workforce in the greater L.A. area. While the chapter is the shortest of the book’s main chapters, it does well exploring how monopoly capital looked at L.A. as a potential utopia for its anti-worker businesses. Big companies like B.F. Goodrich, Bethlehem Steel, Proctor & Gamble, and many others collaborated to create local laws, a violent anti-labor police force with a “Red Squad,” and a network of “civic groups” (well-trained vigilantes) in the American Legion and Kiwanis.

Within this violent and exploitative system, workers reported just enough wages to feed themselves and pay rent daily. Filipinos, South Asian, and Mexican workers were recruited to create a vast reserve army of labor that could be deported, abused, and imprisoned with impunity if it got too agitated or demanded too much. Communist Party work, the international origins of the workers, and the struggle for relief and the right to organize fostered a new internationalism that shaped L.A.’s working-class communities for decades.

The final chapter on the life of Black artist Elizabeth Catlett follows the revolutionary activist from her early years studying art in Iowa and Chicago, her marriage to Charles White, and her ultimate resettlement in Mexico. Traveling with a major art fellowship to study and practice in Mexico City, Catlett was thoroughly invigorated by that city’s artist community, which included Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and the lesser-known artists at the Taller de Gráfica Popular. The chapter focuses primarily on Catlett’s political role in the U.S. before her decades-long residence in Mexico and the substantial body of work she produced. Unfortunately, only a handful of black-and-white images of her work (the cover and in the inset) are included in the book.

Heatherton’s Arise! provides a groundbreaking analysis of the Mexican Revolution and its profound impact on the emergence of global radicalism. By tracing the development of revolutionary internationalist consciousness in the Americas, Heatherton sheds light on the transformation of localized working-class politics into a movement with international aspirations. The book’s meticulously crafted chapters unveil the role of key figures such as Magón, Kollontai, Catlett, and numerous others in shaping and advancing the ideals of radical labor organizing and internationalism. Furthermore, Arise! stands as an invaluable addition to the existing scholarship on internationalism, building upon the works of previous researchers and providing a comprehensive understanding of the historical context and significance of the Mexican Revolution within the global revolutionary movement.

Christina Heatherton

Arise! Global Radicalism in the Era of the Mexican Revolution

The University of California Press, 2022

336 pp., $29.95

ISBN: 9780520287877

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments