From New York to California, from Florida to Michigan, millions of Americans are lining up in cars stretching for miles and miles in desperation to stave off the grim specter of hunger, waiting hours for food. U.S. capitalism at its worst, the grim reaper of starvation, is descending on hapless families. The rapacious rich can gather in their palatial mansions and sit down to sumptuous platters of the most delectable of foodstuffs and feast to their heart’s delight. But not the workers, the toilers, the poor. The coronavirus has exposed the fragile underbelly of the so-called “Great Economy” in the United States.

Recently, a columnist asked, “What are hungry Americans to do when the food banks don’t have any more food for them?” This question was hauntingly answered with simply another question: But if things are this bad at the very start of this new economic downturn, what are things going to look like a few months from now?

In New York City, food banks are running so low on sustenance that an immigrant resident said that she was living on one meal a day. Obviously, not enough to maintain a healthy existence.

In Texas, a county of 35,000 where food pantries have declined from six to three with the advent of the economic crisis, an elderly couple cuts back on already meager daily meals.

The Greater Baton Rouge Food Bank has only a few weeks of food left. At the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, traffic was backed up for miles. Dozens of cars had lined up at 9 AM even though the food center didn’t open until 12 noon, but in the end, hundreds of vehicles were turned away.

In Council Bluffs, Iowa, food bank officials arrived an hour early at the distribution center and found the streets jammed with cars in every direction with the police directing traffic. The center had only enough boxes of food—produce, bread, and milk—for 200 cars; the rest left with nothing. Some parents had shown up early with their children and had to leave empty-handed.

“Hungry people are hungry each and every day” is the observation of food bank officials in Washington state. This state has gone from 800,000 “food insecure” (the term is a bit of a misnomer) citizens to 1.6 million since the inception of COVID-19. Food boxes in Washington typically consist of canned chicken, macaroni and cheese, and peanut butter.

In Chicago, 112 area food pantries have closed. This is almost a quarter of the 370 distribution centers supplied by the Greater Chicago Food Depository. Countless Illinoisans are impacted by these closings.

In Las Vegas, there were 180 food pantries before COVID-19. Now, there are only 10 left with another 21 drive-thru distribution sites. This is in part because of the closings of nearly all gambling and tourist attractions according to the Three Square Food Bank. At each drive-thru, 200-250 cars were expected per day, but there are now 500-600 cars arriving a day with lines up to four miles long.

In San Antonio, an incredible 10,000 families began arriving at the crack of dawn to receive survival boxes when normally only 300 to 400 families show up on any given day. Parents who have been laid off from their jobs at amusement parks, housekeeping jobs, and restaurants showed up with little children hoping to get a share of the boxes of chicken, rice, beans, fruits, and vegetables.

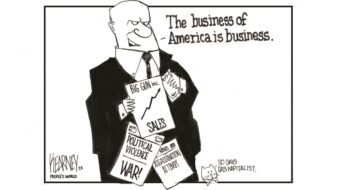

With long lines for food, families now typically wait hours for food boxes. As one reporter recently commented, “The richest country in the world and people are starving.” Another newsperson recently quipped, “This does not sound like a superpower.” This writer would add the U.S. now sounds more akin to a “failed state.”

Most food banks are now experiencing a shortage of not only food but also of volunteers to distribute it. Many of the grocery stores, hotels, and restaurants that were a source of the survival boxes are no longer available. In the case of supermarkets, their shelves are running short because of irrational hoarding by the more affluent, and countless restaurants have closed. In regard to volunteers, most of these were the elderly and the retired who are now loath to risk their lives, as they see it, from infection, operating food banks.

Sources that normally share surplus inventory approaching the “best by” date have less to donate. As a consequence, food banks now have to buy what they used to have donated—the food they used to get for nothing.

The survival boxes, to cite an example, contain such edibles as chicken noodle soup, tuna fish, and pork and beans, while other food boxes containing eggs and fruit are the bill of fare. Hardly the most balanced of meals, but at least starvation is averted.

This crisis begs the question alluded to earlier: What happens when the food banks have no more food? The people—men, women, children, the elderly; parents and their children—cannot be expected to starve. What will be capitalism’s response to this unprecedented crisis?

Comments