LOS ANGELES—Ben Shahn was moved in the early 1930s to paint a series of works based on the infamous Tom Mooney case. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) currently has a display of these works and other objects related to the case in a small but historically important exhibition called “Shahn, Mooney, and the Apotheosis of American Labor.” It is on view through November 25, 2018, in the museum’s Resnick Pavilion. Students of American labor history should not fail to see it.

Who was Tom Mooney?

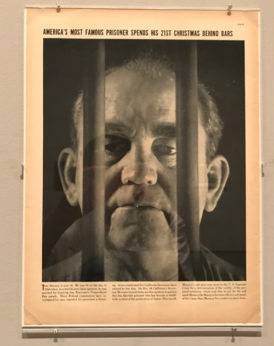

Tom Mooney (1882-1942) became a martyr of the labor movement and the subject of a worldwide campaign to free him from unjust life imprisonment. He had been convicted for placing a bomb which went off at a 1916 San Francisco Preparedness Parade, part of Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s warm-up campaign for entry into World War I. The bomb killed ten and wounded sixty. Mooney’s conviction, however, was based on perjured, paid-for testimony. In one of his appeals, a hard alibi for Mooney was brought forward: A photograph of him in San Francisco that day that included a large jeweler’s clock, and the time read 2:01. The bomb went off at 2:06 almost a mile away; Mooney could not possibly have committed the act.

Mooney had earlier been a suspect for dynamite explosions connected to labor strife, but authorities could never pin him down. At the Preparedness Parade, there were anti-war activists from the IWW and other unions protesting entry into the war, so Mooney was simply picked up and charged. He was convicted, given a death sentence in 1917, and sent to San Quentin federal penitentiary. But the evidential record was so thin that his sentence was commuted to life.

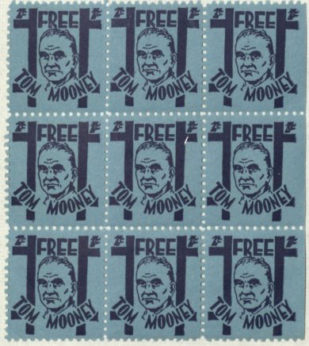

Arrested at the age of 33, for more than twenty years Mooney became a pawn in the complex power struggle among unions, municipal and state politicians, and American business. Even Pres. Wilson pleaded for mercy because of the scandalous trial. Three federal commissions reported his case as a frame-up, but seven courts and five California governors refused to free him. Ultimately his imprisonment became a cause célèbre for the worldwide labor, socialist and communist movements. “Free Tom Mooney” was added to every list of demands put forward by the left.

My most informative LACMA docent, Joan Schrier, who guided me through the small one-room exhibition, stopped me midway because she already knew the joke I started to relate. For our PW readers I’ll tell it now as a sample of the American labor movement’s sense of humor at the time:

There was a militant rent-strike on New York’s Lower East Side. It went on for months, through a bitter winter and into a sizzling hot summer and fall. The angry tenants wouldn’t desist from their daily demonstrations in front of the landlord’s buildings and even in front of his comfortable suburban home. Eventually, the loss of income and the shaming brought the owner to the table for a settlement of their grievances.

“All right,” he said. “I’ll fix the plumbing and repair the radiators. I’ll bolt the fire escape securely to the wall and have it checked for safety every year. I’ll call in the exterminator for the cockroaches and the rats. I’ll repair the holes in the ceiling and the rotten floorboards. I’ll replace the glass in the broken windows. I’ll make sure the lights work in all the hallways, and install a buzzer system for the outside door. But I can’t free Tom Mooney!!”

The LACMA show identifies this campaign as “the apotheosis of American labor.” I’m not sure where they got that phrase from, but in any case there was never a single issue in the American labor movement which earned such widespread solidarity as the Tom Mooney case, especially in the years following the 1927 execution of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, and in the 1930s when the Communist Party started growing exponentially. The CPUSA-backed group International Labor Defense (ILD) was instrumental in keeping the Mooney case in the forefront of public consciousness.

And as the years passed, broad swaths of the American people started wondering if Mooney hadn’t been right to question the World War: The “war for democracy” seemed in retrospect more of a propaganda hysteria to send a nation into battle for unprecedented profits. Mooney was called “the American Dreyfus,” a reference to the infamous case of a Jewish French officer falsely convicted of treason whose cause also became a rallying cry for justice.

Who was Ben Shahn?

He was born in Lithuania, part of the Czarist empire, into a Jewish family in 1898. Shahn’s father was exiled to Siberia for anti-Czarist activity, and his mother took him to America, where after his escape the father later joined them. They lived in the poor neighborhood of Williamsburg in Brooklyn. Shahn (1898-1969) studied lithography and became well known for his series of gouaches on the Sacco and Vanzetti case. As a socially conscious artist, he spent a year or so working as an assistant to Mexican muralist Diego Rivera on the Rockefeller Center project, and Shawn himself became known as a muralist as well as an accomplished photographer. In the early 1930s, he became interested in the Tom Mooney case and is thought to be the only artist to dedicate a series of works to that cause.

This exhibition celebrates one of Ben Shahn’s significant early social commentaries, Apotheosis, 1932–33, acquired recently by LACMA. Apotheosis is the last and largest painting of his series of 16 gouaches devoted to Tom Mooney. It comprises images he had previously created of Mooney’s Irish immigrant mother, who spent the last years of her life trying to free her son, traveling all over the U.S. and abroad, even to the USSR, to speak on his behalf. Also included were images of Mooney himself at the center of what could be called a triptych, the California Supreme Court that declined to set him free, and a recreation of his painting “A Study in Expressions at Communist Demonstration,” based on a New York Telegram photo of the May Day demonstration of 1932. Notable is the jeweler’s clock at 2:01.

The exhibition, organized by LACMA and at least in its literature not indicated to be traveling elsewhere, focuses on the campaign to free Mooney through assorted political cartoons, pamphlets, and films. There is footage of the 1916 Preparedness Parade itself, complete with labor unions and military units marching, as well as the participation of suffragists dressed in white. A later film has Mooney speaking to the camera from his prison in 1933—by then he had been reinstated back in San Francisco County Jail—where he professes his undying loyalty to the working class. His three lawyers also make a brief statement.

The heart of the show is Shahn’s artistic response, including a selection of gouaches from the Mooney series and the documentary photographs from newspapers that inspired the artist.

In the display case are an original copy of the ILD pamphlet on the Mooney case, with illustrations by the well-known left-wing artist Anton Refregier and an introduction by novelist Theodore Dreiser; a 1930 drawing of “Tom Mooney’s May Day Smile” by another radical artist, Hugo Gellert, who had gone to San Quentin to visit the famous prisoner; a cartoon by Robert Minor in vol. 1, no. 1 of The Liberator (March 1918) depicting Mooney about to be hanged, with the caption, “Will You Let Them Do It?”; a copy of Selden Rodman’s 1951 biography of Shahn open to the page showing the artist at the Downtown Gallery at 113 W. 13th St. in New York City, where the Mooney series was first shown in 1933.

On display is also a copy of the gallery brochure with a significant statement by Diego Rivera, reading in small part, “Ben Shahn has discovered the just note for his work now that his subject matter is the struggle of the proletarianized American petit-bourgeois intellectual against the degeneration of the European bourgeoisie transplanted on this continent. His ability and his esthetic qualities are magnificent, as witness the fact that he is accepted by the most sophisticated connoisseurs of art as well as by the masses of workers.”

We also find a copy of the sheet music for a song “Tom Mooney (No. 31921)” [his prisoner number] by lyricist Pearl M. Wright and composer Sylvester L. Cross; Free Tom Mooney fundraising stamps; and various other items.

Mooney was eventually pardoned and freed in 1939 but was not able to enjoy his freedom very long. He died in 1942.

The LACMA website can be accessed here. LACMA is located at 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles 90036.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.

Comments