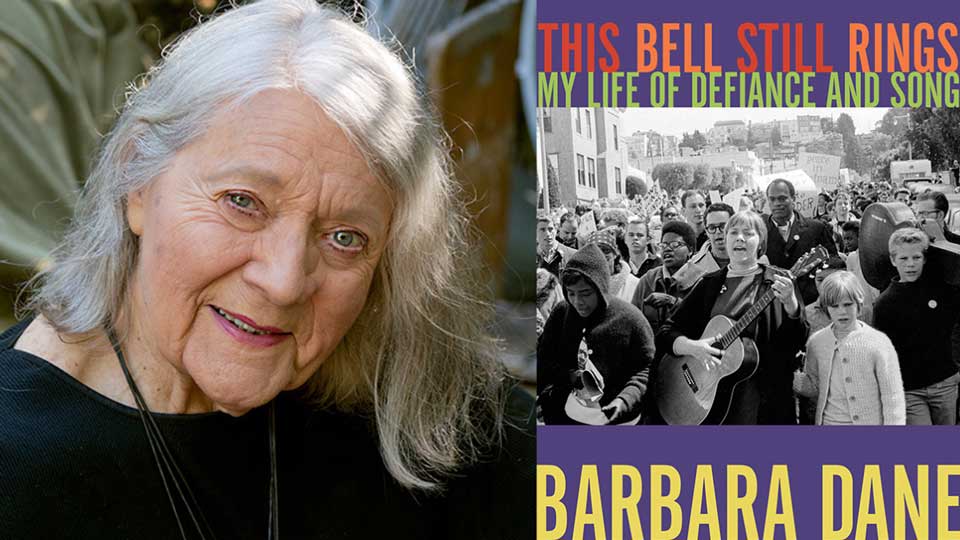

Editor’s Note: On Oct. 20, 2024, just a few weeks after this review was published, Barbara Dane died at the age of 97.

It must be quite a daunting challenge to start writing an autobiography when you’re over 90! But that’s exactly what movement singer and organizer Barbara Dane has done, and it is a beaut! What amazes me is the ready access she seems to have enjoyed to a vast archive not only of memory itself but of physical evidence—recordings, films, photographs, press coverage, calendars—and a host of fellow artists with whom she collaborated over what for most other performers would have been two or three-lifetime careers.

Dane worked in almost every vocal genre—jazz, blues, folk, classical, and theater. She gave her all to everything she did, and it was all “for the cause.” Even in the substantial portion of her career when she resurrected the almost forgotten songs of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, she presented them not only authentically from a cultural point of view—which received the blessing of the greatest Black performers in the nation—but always with the explanation of how strong a woman you had to have been to compose and perform those songs in their day.

In the course of reading Dane’s book, I had occasion more than once to mention her to friends, and I was surprised that even in socially conscious circles, I encountered some who did not know her name. Either they were born too late to experience her in her heyday, or their musical tastes and hers never managed to cross paths. As I absorbed her story, I realized I was familiar with only a fraction of her work. I knew a couple of her recordings, such as I Hate the Capitalist System, but what I most remembered her for was Paredon Records, her project, along with her third husband Irwin Silber, of recording authentic repertoire of protest and liberation songs from the many emancipation movements across the globe. They would gladly send me media copies for airing on a college radio station I was associated with in the 1970s.

And I was also unaware of her book until now. A couple of months ago, I attended a fundraiser for the Center for the Study of Political Graphics here in Los Angeles. Barbara Dane was given their annual award for lifetime achievement. Living in Oakland as she does now, and at 97, she did not feel up to the trip, so we heard her acceptance speech via video. But her son Pablo Menéndez attended, sang, and spoke of his mother and had copies of the book on hand. I actually had met Pablo more than once, as he used to perform with his band Mezcla at La Zorra y el Cuervo jazz club in Havana, where he’s made his life since he was a teenager. I’d take some of my trippers to that club on Jewish solidarity visits to Cuba in the early 2000s.

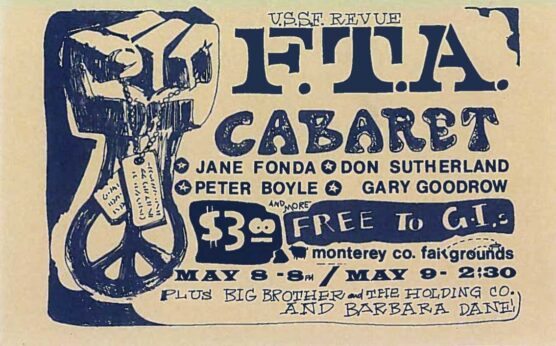

There’s hardly a venue where Barbara Dane never sang—from small jazz and folk clubs to huge protest marches and demonstrations, from GI coffeehouses during the Vietnam War to major concert halls across the globe, from youth festivals in socialist countries (her first was Prague in 1947) to jazz, folk and women’s music festivals at home. The number of great names in the jazz and folk worlds with whom she worked is positively dizzying—and I barely recognized half of them. Happily, for a book this size that covers so much territorial and esthetic ground, there’s an excellent index!

There’s hardly a venue where Barbara Dane never sang—from small jazz and folk clubs to huge protest marches and demonstrations, from GI coffeehouses during the Vietnam War to major concert halls across the globe, from youth festivals in socialist countries (her first was Prague in 1947) to jazz, folk and women’s music festivals at home. The number of great names in the jazz and folk worlds with whom she worked is positively dizzying—and I barely recognized half of them. Happily, for a book this size that covers so much territorial and esthetic ground, there’s an excellent index!

What leaps out from Dane’s memoir is her spirit—loving, cooperative, collective-minded, generous, risk-taking, humble, and warmly contemplative. Many readers will be fascinated to accompany her each step of the way as she explores one venture after another—a new jazz club, a new city, a cross-country trip, a new husband, the music business, the growth of her three children (all involved with music one form or another). What I found the most ingratiating feature of her book is the paragraphs she inserts as a kind of autumnal summation—of a relationship, of a phase of her life, of a movement, of a historical moment. And having lived to her upper 90s now (she was born in 1927), she’s had the chance to reflect on so many of these.

It’s a long book, and it helps that she has divided up her life into four parts, each with a number of short chapters and lots of informative black-and-white photos. There are very few passages where I found myself tired of all the names, venues, moves, and domestic troubles. But even an epic life will have its dark phases, right?

Dane was a feminist long before she knew the word—insisting on taking woodworking classes in grade school instead of sewing. She picked up instruments and played and sang. She experienced racism first-hand in Detroit, where her father had a little drugstore. A Black man entered, and she served him a Coke, and in short order, her father threw him out. She has been a dedicated anti-racist ever since. Before long, she had encountered members of the American Youth for Democracy, People’s Songs, and the Communist Party, with which she would have a complicated history. She married a veteran, Rolf Cahn. The Blacklist of the 1950s cast a long shadow over her life and career, but she does not sound resentful.

Here’s a good example of how Dane reflects philosophically on her life:

“Reading through copies of FBI files recently released to me from the National Archives, I know now that it was Rolf himself who was ‘Informant T-1,’ the person who had supplied them with a copy of my party card, along with some other bits of personal details. According to the file, he informed them of something or other related to me on at least five different occasions in 1952 after we had separated. No harm done, really, because I have never had anything to hide and would have shown the card to them myself if they had asked. It was still a legal party, after all. Perhaps the FBI, knowing I had just left him, saw him as vulnerable at the moment and pursued him. As a soldier, Rolf had been recruited for espionage work by the Office of Strategic Services, a precursor to the CIA, so perhaps he still had some romantic sense of ‘duty,’ or perhaps the idea of being an informant seemed exciting to him. Maybe it was out of bitterness. Maybe he needed the money. (Was there money?) Not for me to say. But it wounds my heart to think that he might have gone out of his way to do this. I hope it wasn’t like that.” (pp. 86-87)

Dane had lost her political home and family when she and Rolf were expelled from the CP—which, to me, sounds like one of his machinations. However, she remained close to its politics, and the socialist bloc never seemed to have any trouble with her. “But I’ve never gotten rid of my craving for some sort of collective, for a group of collaborators with whom I could discuss and determine and who would have my back, just as I would have theirs” (p. 393). Perhaps it’s time for Barbara to rejoin!

Dane’s memories are full of trenchant stories about such figures as Tillie Olsen, Malvina Reynolds, Bob Dylan, the Chambers Brothers, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Muddy Waters, Memphis Slim, Estella “Mama” Yancey, Lenny Bruce, Fanny Lou Hamer, Bernice Reagon, Ed Pearl of the Ash Grove in L.A., artist manager Joe Glaser, Mikis Theodorakis, and no less than Fidel Castro.

Her treatment of her third husband, Irwin Silver, perhaps the greatest love of her life, is saturated with that sense of loss of connection to a movement group. Silber became part of the Line of March crowd, which Dane apparently never bought into. Though collaborators in life, he had his interests and projects, and she had hers. Here’s how she assesses the demise of the Soviet Union:

“That first noble experiment called the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), built by millions of mostly illiterate former serfs on the ashes of the corrupt and seemingly indestructible Tsarist regime, was dedicated to building a society based on the needs of the people rather than the demands of capital. And against all odds, it was sustained for an incredible sixty years despite suffering over twenty million casualties, mostly civilian, in World War II. In the end, that first experiment may have collapsed in the face of insurmountable challenges both from within and without, but the goal of someday achieving a world built on genuine socialism is still alive. This vision has never been abandoned. Not by me, and not by millions of others. Call me crazy, but that’s the fountain where I still drink from the waters of hope.” (p. 128)

For the record, Dane makes a few editorial errors, such as spelling (Madame Schumann-Heink, vocalise, Anna Sokolow, Sidney Finkelstein). She wrote “International” instead of Industrial Workers of the World (p. 245), and it was the Southern Student Organizing Committee (p. 294). She gets her directions reversed when she speaks of “Manhattan, north to south roughly 145th to 155th Streets” (p. 196). She speaks of Cuba as “half the size of California” (p. 320), when it’s just a bit over a fourth the size and cites over 20 million Soviet casualties in WWII when the estimate is now over 25 million dead (and the Soviet experiment lasted not 60 but 70-odd years).

Dane mentions “the one-hundred-plus Lincoln Brigade volunteers from the US who sacrificed their lives to fight fascism” (p. 352); the VALB (Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade) puts that number more in the vicinity of 800. And there’s the impossible statement “Joe Sims, a fifteen-year-old kid from Youngstown, Ohio, with a big unruly Afro, who first attended the World Youth Festival in 1951 in Berlin” (pp. 55-57). Joe was not even born by 1951. He did attend the WYF in Berlin in 1973. Sometimes, she uses a foreign word and does not translate it for the reader.

I learned a few new words from this book, too: galluses, dogsbody, coverture. I’m happy she shares some of the lingo she picked up in her jazz and beat circles. I was amused to hear for the first time the expression “on the emes (truly)” (p. 142)—though it might have been helpful to say that emes derives from the Yiddish and Hebrew word for “truth.”

Barbara Dane sums up her artistic credo like this: “No manager has ever owned me or told me where I had to sing or what to sing, or even how to sing it. I have no regrets, and, more important, this has taught me a fundamental truth: that every time an artist refuses to do something or become something that violates their ethics or integrity, the more free that artist becomes.”

At the conclusion of her book Dane shares “Some Rules for the Road Ahead,” a dozen tenets worth holding onto. My favorite is this one: “My understanding of the world is actually pretty simplistic. I see life breathe in and breathe out. I see people come together and then disagree, only to find common ground again when conditions are right. Nothing is ever perfect, but it is in the imperfections that creativity dwells, that discovery and enlightenment await. Just don’t get your mind to believing there is a permanent, complete, and perfect world anywhere.”

This is one wild helluva ride through the 20th century.

Barbara Dane

This Bell Still Rings: My Life of Defiance and Song

Berkeley: Heyday, 2022

488 pp., black and white photos, discography, index

ISBN: 9781597145817 hardcover

Also available as an ebook