For a while, it looked like it wasn’t going to happen and baseball parks would be as empty as they were in 2020 due to the pandemic. But this time, it was the virus of greed that locked the players out and put the entire 2022 baseball season in jeopardy. Fortunately, the owners came to their senses and made reasonable concessions to the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), which allowed for a shortened Spring Training. And now that what used to be called “Our National Pastime” is back, it’s time to look at several recently published books about the game that would be of interest to People’s World readers.

Many fans know that baseball is the most popular sport in Japan, but they probably aren’t aware that the first game in Japan was played in 1873. In the early 20th century, amateur and university baseball became widespread, and the first high school championships were held in 1915. After World War II, the Nippon Professional Baseball League started play in 1949, and today there are two leagues, the Central and Pacific.

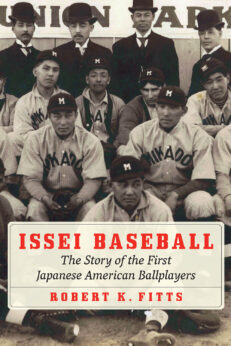

But the first Japanese professional baseball team was assembled not in Japan, but in Los Angeles in 1905. Robert K. Fitts’s Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers is the story of how several reporters at a small Japanese newspaper formed the Japanese Base Ball Club of Los Angeles, a team that would play games across the country in 1906 and 1911.

But the first Japanese professional baseball team was assembled not in Japan, but in Los Angeles in 1905. Robert K. Fitts’s Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers is the story of how several reporters at a small Japanese newspaper formed the Japanese Base Ball Club of Los Angeles, a team that would play games across the country in 1906 and 1911.

The catalyst for the popularity of baseball in Japanese communities on the West Coast was the arrival of the Waseda University team in April of 1905. The 12 squad members would end up playing several college teams, as well as regional amateur clubs. The tour was a success as Waseda was competitive with the American teams and Japanese support at the games was enthusiastic.

In 1906, the Los Angeles team began a barnstorming tour where they played town teams as far east as Indiana. They finished the tour with a record of 122-20 and the respect of most fans and opposing teams in middle America. Surprisingly, there was little animosity directed at the Japanese players. Upon returning to Los Angeles, the players decided to keep together—and the Japanese Base Ball Association was born.

In May 1911, the JBBA embarked on another national tour that would take them to Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa. This time, the club was not as successful as the 1906 team, losing more games than they won, but they drew large crowds in the mostly small towns where they played. It was not a financial success either. Because of rainouts and unexpected expenses, the players returned home broke. That spelled the end for the JBBA.

Fitts goes into detail about many games during the tours which hardcore fans might appreciate, but it makes for a disjointed narrative. That minor quibble aside, Issei Baseball fills a gap in our knowledge of the impact of baseball on the Japanese in early 20th-century America.

That infamous 1919 season

The 1919 season will forever be remembered as the year the Chicago White Sox became the “Black Sox,” as it was the first World Series that was fixed—or at least the first proven to be so. There were teams before then that many believed took money from gamblers to throw games. It was common knowledge that contests were routinely decided by questionable pitches and fielding plays, and the legitimacy of professional baseball was viewed with suspicion.

There have been quite a few books about the Black Sox, but Don Zminda’s Double Plays and Double Crosses: The Black Sox and Baseball in 1920 is the first to tell the story of the 1920 season. Rumors that the previous year’s Series had been thrown by a number of players were rampant, but there had yet to be an official investigation. A grand jury established to look into accusations wasn’t convened until late September 1920, which meant that the entire 1919 team was able to play that season.

There have been quite a few books about the Black Sox, but Don Zminda’s Double Plays and Double Crosses: The Black Sox and Baseball in 1920 is the first to tell the story of the 1920 season. Rumors that the previous year’s Series had been thrown by a number of players were rampant, but there had yet to be an official investigation. A grand jury established to look into accusations wasn’t convened until late September 1920, which meant that the entire 1919 team was able to play that season.

Zminda’s book is an in-depth analysis of that season. He looked at almost every White Sox player and found numerous occasions when it appeared that some Sox fielders were not making plays they normally would have and batters looked lost at the plate. Zminda intimated that the 1920 season was possibly as crooked as the 1919 Series had been and that 1917 was probably just as bad. The trial after the season of the alleged fixers would find all the defendants acquitted. But the Commissioner of Baseball ignored the verdict and banned eight Sox players from ever playing professional baseball again.

Zminda concludes that Sox players did throw games in 1917 and 1920, and the ending of the 1920 season was as tragic as 1919: the Sox threw games in August and September, which prevented them from another appearance in the World Series.

Cheatin’ by sign stealing

Former NFL star LaDainian Tomlinson was quoted as saying, “If you ain’t cheatin’, you ain’t tryin.’” Whether he said it in jest or not, the Houston Astros took it to heart, resulting in the greatest scandal in baseball since 1919. If it hadn’t been for former Astros pitcher Mike Fiers, the scheme might never have been exposed. Fiers disclosed that during the 2017 season, which culminated in Houston winning the World Series, the team stole signs that catchers would show to pitchers. This by itself was not unusual; teams have been stealing signs for at least the past 70 years. The difference was that Astro players stole signs using electronic means. As a result, Houston batters knew in advance what kind of pitch the pitcher was going to throw. Why was this important? If a batter knew the next pitch would be a fastball or breaking pitch and what side of the plate it would cross, he’d have a huge advantage.

There were electronic means of sign stealing in the past, but the Astros perfected the practice. The fact that Houston won the World Series utilizing this method has called into question the legitimacy of their World Championship. Cheated: The Inside Story of the Astros Scandal and a Colorful History of Sign Stealing by Andy Martino goes into detail as to how they were able to get away with it.

There were electronic means of sign stealing in the past, but the Astros perfected the practice. The fact that Houston won the World Series utilizing this method has called into question the legitimacy of their World Championship. Cheated: The Inside Story of the Astros Scandal and a Colorful History of Sign Stealing by Andy Martino goes into detail as to how they were able to get away with it.

Martino begins with a brief history of sign stealing, some means legal, others highly questionable. Perhaps the most famous of these was a telescope and buzzer system used by the 1951 New York Giants. Since then, there have been increasingly sophisticated uses of video by looking at the previous day’s game. But the Astros took this to another level. They installed a video monitor in their dugout so they could see a catcher’s signals in real time. Players in the dugout would then let the batter know what the next pitch was going to be by banging on a trash can in the dugout. Other teams knew something suspicious was going on, but they couldn’t prove it until Fiers blew the whistle.

Consequently, baseball banned video monitors in the dugouts. This season has seen electronic communication between pitcher and catcher so there would no longer be a need for signs. But the Houston Astros’ 2017 World Championship will forever be tainted, and to some, they will always be known as the “Blackstros.”

Four men who changed baseball

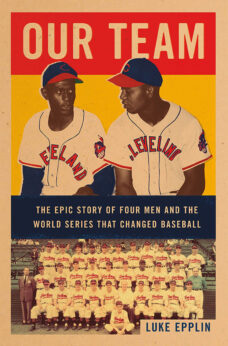

The Cleveland Indians (now Guardians) last won the World Series in 1948. Luke Epplin’s Our Team: The Epic Story of the Four Men and the World Series That Changed Baseball focuses on those four men: Bob Feller, Leroy “Satchel” Paige, Larry Doby, and Bill Veeck. Feller arrived in the majors in 1938 with a bang: as a 17-year-old still in high school, he pitched his first complete game, striking out 15 and allowing only one run. “Rapid Robert” went on to win 148 games over the first nine years of a storied career, but he entered the 1948 campaign coming off an injury and had outraged fans by appearing to care more about making as much money as possible in the offseason instead of winning ballgames for Cleveland.

The Cleveland Indians (now Guardians) last won the World Series in 1948. Luke Epplin’s Our Team: The Epic Story of the Four Men and the World Series That Changed Baseball focuses on those four men: Bob Feller, Leroy “Satchel” Paige, Larry Doby, and Bill Veeck. Feller arrived in the majors in 1938 with a bang: as a 17-year-old still in high school, he pitched his first complete game, striking out 15 and allowing only one run. “Rapid Robert” went on to win 148 games over the first nine years of a storied career, but he entered the 1948 campaign coming off an injury and had outraged fans by appearing to care more about making as much money as possible in the offseason instead of winning ballgames for Cleveland.

Larry Doby, the second African-American in the majors, was also suspect in many fans’ minds. Doby struggled through a difficult first season, hitting only .156 with no home runs and two RBIs in 33 plate appearances. But 1948 would be his breakout year as he became the starting centerfielder and hit .301 with 14 home runs and 66 RBIs. Doby was on his way to a 15-year Hall of Fame career.

The other 2 men, Satchel Paige and Bill Veeck, were by far the most interesting of the four. Paige was a legend in the Negro Leagues and had impressed many white fans by his success against major leaguers in exhibition games. He was a showman in addition to being a great pitcher. In some games, Paige would tell the hitter what kind of pitch he was going to throw and then proceed to strike him out to the delight of the fans. On more than one occasion, he had all his fielders (except the catcher) stay on the bench and then struck out the side, proving he didn’t need them behind him. But in 1948, Satchel turned 42, and his best days appeared to be behind him.

Cleveland owner Bill Veeck didn’t care. He knew that Paige could still pitch and would be able to help his team. So on July 6, Satchel Paige was finally able to sign a major league contract. Some scoffed at the signing, believing Veeck had done it just for the publicity. But three days later, Paige came on to pitch in relief and allowed only two singles in two innings. His last pitch resulted in a fly ball to the left fielder. The moment the batter hit it, Paige walked off the mound to the dugout, confident that the batter would be out. The old confident showman was back. Satchel went on to solidify the pitching staff, winning six games to only one loss and posting a superb 2.48 ERA.

If Paige was a unique personality on the mound, Bill Veeck was also a unique owner in the history of baseball. Veeck bought the Cleveland franchise on June 22, 1946, and spent the afternoon at the ballpark, roaming throughout the stands, talking with fans and asking for their input. The city fell in love with Veeck, and attendance rose dramatically. He became the P.T. Barnum of baseball, shooting off fireworks after games, hiring baseball clown Max Patkin to entertain fans between innings, and staging a 100-yard foot race between George Case, the Clevelanders’ fastest runner, and Olympic Medalist Jesse Owens (it wasn’t even close).

Veeck had been the owner of the minor league Milwaukee Brewers and had wanted to sign Black ballplayers for a number of years. Now that he owned a major league team, Veeck wasted no time and signed Larry Doby midway through the 1947 season. Veeck believed it was not only morally wrong for the major leagues to remain all white, but foolish as well. He knew there were many players of color who could vastly improve team rosters. His signing of Paige was evidence he was right. And it wasn’t just Black players; Veeck hired Black security guards, vendors, ushers, janitors, and groundskeepers.

Veeck sold the club after the 1949 season and went on to own the St. Louis Browns and later the Chicago White Sox. He brought Paige with him to St, Louis, where Satchel had three successful seasons, and at 47 was named to the American League All-Star team.

Our Team is an excellent read, not only for baseball fans but also for those who want to learn more about the trials and triumphs of Black players in the early years of integration on the diamond.

Remember the Pacific Coast League?

In the early 1950s, it appeared that the Pacific Coast League might become the third major league. Many players preferred playing in the PCL as the weather was much better on the West Coast and they played more games (180 vs. 154), which meant more money. But the American and National Leagues conspired to make sure that the Coast League continued to be a step below the majors. And when the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants moved to Los Angeles and San Francisco, respectively, the PCL’s days were numbered. And while the National League was the first to sign a Black player, the PCL was the first professional baseball league to ensure that all teams had African-American players on their rosters.

Jackie Robinson’s breaking of the color barrier in 1947 gave the go-ahead to other teams to sign Black players. San Diego Padres owner Bill Starr signed John Richey, a 24-year-old catcher who had played for the Chicago American Giants in the Negro Leagues, on November 22, 1947. While Richey was an African-American, Starr’s main reason for his signing had more to do with Richey being a homegrown San Diegan who had played at San Diego State University. But Richey proved that he belonged in the PCL by batting .323 in 103 games. Unfortunately, whereas Robinson was largely embraced by the Dodgers, Richey felt that his teammates, although generally supportive, did not have his back on the field: “There was a (Los Angeles) Angel who threw four balls at my head. I took first. My teammates did nothing and there was no retaliation. Another time against the Angels, I got a double. The pitcher came to second base. He was spitting and yelling all kinds of language in my face. Nobody said or did anything and I was lonely. I had to room alone, but I was never refused accommodation in the PCL.”

There had been pressure to integrate professional baseball for a number of years. In 1942, lawyer and a national leader of the CPUSA William L. Patterson had a meeting with Phil Wrigley, owner of the Los Angeles Angels, where he argued that “the Jim crow pattern of baseball [needs to be] changed.” Wrigley agreed, but said, “I don’t think the time is now.” His fellow owners agreed—until the Brooklyn Dodgers changed the game forever.

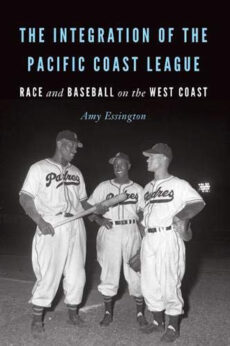

In The Integration of the Pacific Coast League: Race and Baseball on the West Coast, Amy Essington goes through every team and documents their first Black players and the problems they encountered. San Francisco Seals manager Lefty O’Doul and Seattle Rainiers manager were racists who did what they could to keep their teams all white. Seals player Barney Serrell said, “O’Doul would let Black players cash our check in his bar, then he would not even let us get a beer. Cash the check, then we would have to go.”

In The Integration of the Pacific Coast League: Race and Baseball on the West Coast, Amy Essington goes through every team and documents their first Black players and the problems they encountered. San Francisco Seals manager Lefty O’Doul and Seattle Rainiers manager were racists who did what they could to keep their teams all white. Seals player Barney Serrell said, “O’Doul would let Black players cash our check in his bar, then he would not even let us get a beer. Cash the check, then we would have to go.”

Hall of Fame second baseman Rogers Hornsby was quoted as saying, “Negro players ought to stay in their own league where they belong…They’ve been getting along alright playing together.” Not surprisingly, Seattle was the last PCL team to sign Black players when they added Bob Boyd and Artie Wilson in 1952.

A labor of love that saw her combing incomplete archives, Essington has written the definitive study of integration in the Pacific Coast League, and baseball fans are fortunate that she did.

On March 30, 2005, the Padres honored John Richey as the Jackie Robinson of the Pacific Coast League when they unveiled a bronze bust of him at their ballpark.

Whispers

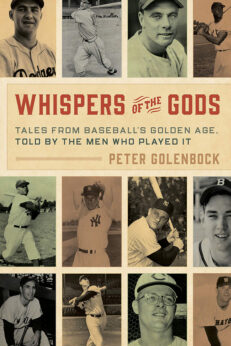

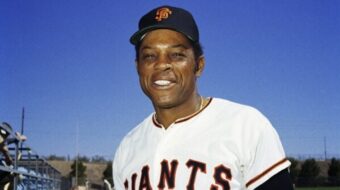

Those of us baseball fans who came of age in the 1960s feel blessed that we were able to see some of the best ballplayers of all time. Willie Mays, who just celebrated his 91st birthday, is considered by many to be the greatest living ballplayer (and when he passes, some of us will see him as the greatest ballplayer ever). Hall of Famers Stan Musial, Ted Williams, Monte Irvin, Phil Rizzuto, Ron Santo, and Roy Campanella are just a few of the ballplayers from the 1950s and 1960s Peter Golenbock was able to interview for his Whispers of the Gods: Tales from Baseball’s Golden Age.

Relief pitcher Jim Brosnan was the first to write a literary memoir of his experiences throughout an entire season, and his account, The Long Season, is considered to be the best of the genre he created. His next book, Pennant Race, a chronicle of the Cincinnati Reds National League Championship season in 1961, is considered by many to be his best. In the Golenbock interview, Brosnan shared one of the worst-kept secrets in baseball: “For (Gil) Hodges, you just had to hit the corner with a slider, and he couldn’t touch it. I often wondered how he could hit 36 home runs a year if you can pitch him so easily. Then I began to understand: if he didn’t swing at that pitch, it was called a ball. Only the veteran pitchers got that called, but it took years for a pitcher to develop that rapport with the umpires. Robin Roberts could pitch that far off the plate. Warren Spahn could pitch that far off the plate on either side. The last couple of years he played, Spahn didn’t throw a ball over the middle fourteen inches of the plate.”

Relief pitcher Jim Brosnan was the first to write a literary memoir of his experiences throughout an entire season, and his account, The Long Season, is considered to be the best of the genre he created. His next book, Pennant Race, a chronicle of the Cincinnati Reds National League Championship season in 1961, is considered by many to be his best. In the Golenbock interview, Brosnan shared one of the worst-kept secrets in baseball: “For (Gil) Hodges, you just had to hit the corner with a slider, and he couldn’t touch it. I often wondered how he could hit 36 home runs a year if you can pitch him so easily. Then I began to understand: if he didn’t swing at that pitch, it was called a ball. Only the veteran pitchers got that called, but it took years for a pitcher to develop that rapport with the umpires. Robin Roberts could pitch that far off the plate. Warren Spahn could pitch that far off the plate on either side. The last couple of years he played, Spahn didn’t throw a ball over the middle fourteen inches of the plate.”

Red Sox star Ted Williams, possibly the greatest pure hitter in baseball history, argues for the enshrinement of Black Sox outfielder Joe Jackson in the Hall of Fame. He relates a conversation he had with Eddie Collins, second baseman on the 1919 Black Sox but who was not one of the fixers. Collins said, “Ty Cobb told me he thought Joe Jackson was the greatest natural hitter he ever saw. And Babe Ruth said, ‘I tried to copy him.’” Joe Jackson is still waiting to get his posthumous plaque in the Hall of Fame.

Roy Campanella was one of the greatest catchers to ever play in the majors, winning the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1951, 1953, and 1955. When he broke in during the 1948 season, he was the third African-American to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Campanella’s career was cut short by a car accident in January 1958 that left him paralyzed and in a wheelchair. Golenbock writes, “Despite his disability, Campy was one of the sweetest, kindest men I have ever had the pleasure of meeting.” Campanella related how he met Dr. Martin Luther King: “We played a (Spring Training) game in Atlanta and we got death threats…One was from the Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan in Atlanta…[their] headquarters. It said, ‘If you come to Atlanta, we’ll kill you.’ We had a meeting with Dr. King. He had contacted Mr. Rickey. Dr. King told him, ‘Definitely see that Campanella and (Jackie) Robinson come to Atlanta to play this weekend.’ We went to Dr. King’s home and had dinner and…stayed with him. He told us, ‘Don’t worry about these threats. You carry on just what you’re doing at the level you’re doing it. That’s the greatest thing for our country.’”

The Dodgers held “Roy Campanella Night” on May 7, 1959, at the Los Angeles Coliseum and 93,100 fans showed up to pay tribute to this Dodger great and eventual Hall of Famer. Campanella died on June 26, 1993, at the age of 71.

Peter Golenbock’s Whispers is a jewel of a book, with insights from ballplayers of that era that can’t be found anywhere else. Fans of all ages will learn so much about baseball in the 1950s and ’60s. Hopefully, they will want to further explore “Baseball’s Golden Age.”

Comments