LOS ANGELES — In a recent essay for The Hightower Lowdown, Jim Hightower lays out the corporate justification for leaching out every last penny of profitability from the companies they take over and liquidate. In this model, shareholders hold all the cards — the workers, community, environment, all be damned. Hightower’s article is colorfully titled “Reinventing Business ‘Ethics’: How Corporate Honchos Gave Themselves Cover to Be as Rapacious as They Wanna Be.” You can read it here. As right-wing University of Chicago guru economist Milton Friedman put it, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. Period.”

Two plays now running in L.A. shine a bright light on this soul-killing philosophy, one a world premiere and the other, just as up-to-date, almost 30 years old. They are Vonnegut, USA, adapted and directed by Scott Rognlien, and produced by The Next Arena, based on five early Kurt Vonnegut stories originally written for popular commercial magazines, and the modern classic Other People’s Money by Jerry Sterner, which debuted in 1989. That play became a 1991 film by Norman Jewison starring Danny DeVito, Gregory Peck and Penelope Ann Miller (trailer here).

Vonnegut (1922-2007) is primarily known for his darkly satirical novels, such as Player Piano, Cat’s Cradle, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Slaughterhouse-Five, and Breakfast of Champions. As he grew into a world-famous writer, he assumed the mantle of “responsible elder” in his essays. The American mid-century landscape is the terrain for this play’s “narrative anthology” of uniquely human tales filled with hilarious and touching characters facing an uncertain future.

The mythical town of Ilium, in the industrial Northeast, is home to Federal Forge & Foundry (FFF), “a 24/7 community of workers,” where a new vice president, the popinjay Newell Cady (Jason Frost), has arrived to modernize production and life itself with his brand of Fordist efficiency. Cady purchases a home in nearby Spruce Falls, and the play shuttles between the vertically integrated industrial plant of 537 buildings and the domestic virtues of small-town America. The nation is at the height of the post-war economic boom, and FFF commits itself to both large-scale manufacturing and home conveniences. A charming feature of the production is the interpolation of upbeat “newsreels” and “commercials” touting the “Make a better tomorrow today” glories of the capitalist apotheosis. The soundtrack bubbles with humorous novelty songs of the 1950s.

I was expecting five short staged vignettes of the Vonnegut stories, but Rognlien instead took these characters, made a village of them, with their stories seamlessly intersecting and commenting on one another. At times the characters break role and speak directly to the audience — although sometimes not especially meaningfully, only anticipating or recapitulating what we see. Advertised as a 90-minute play without intermission, there was one in fact.

In Rognlien’s adaptation, Vonnegut portrays middle America in a warmly glowing, folksy, empathic manner that suggests a visit to Lake Wobegon by Mark Twain. He catches our society at a fulcrum of change, in particular women’s consciousness. This moment at the height of “progress” was the cusp of the Betty Friedan-inspired feminist movement. Here the radically impactful book was Women, the Wasted Sex, or The Swindle of Housewifery, which positively transformed the lives of several characters, and not only those of women. Relationships at both work and home reflect the innate sexist attitudes of the time (that still persist everywhere in places high and low).

Men, too, question if they have eaten of an ideology of hierarchy that no longer nourishes. Some of that awareness comes from the informal “Lovers Anonymous,” a men’s club that meets to survey gender’s shifting tectonic plates. Robert Beddall as Harry Barker plays a sorrowful man divorced from a woman who a decade later appears as a centerfold model. JR Reed plays a Ciceronian character who sells storm windows and inadvertently stumbles on too many bedroom intimacies. The play is appropriate for ages 13 and up.

The overall arc of the play is generally away from individualism and toward a greater solidarity. Absent, however, is the great guarantor of progress in the period, the widespread influence of a unionized workforce, which must have been a factor among FFF’s thousands of employees. And by the way, at that time, in a Northeastern factory with many divisions and departments, some of those workers were black, yet not a single actor in this cast is a person of color. The script may not be about race as such, but it might have been opportune to remind the audience that an integrated workforce in Detroit, Cleveland, Akron, Pittsburgh, created that American middle class way of life that’s now so endangered.

The generous cast of 13 also includes the talents of Keith Blaney, Marjorie LeWit, Carryl Lynn, Darren Mangler, Paul Michael Nieman, Eric Normington, Maia Peters, Paul Plunkett, Rob Smith and Matt Taylor.

“Insightful, timely, and witty”

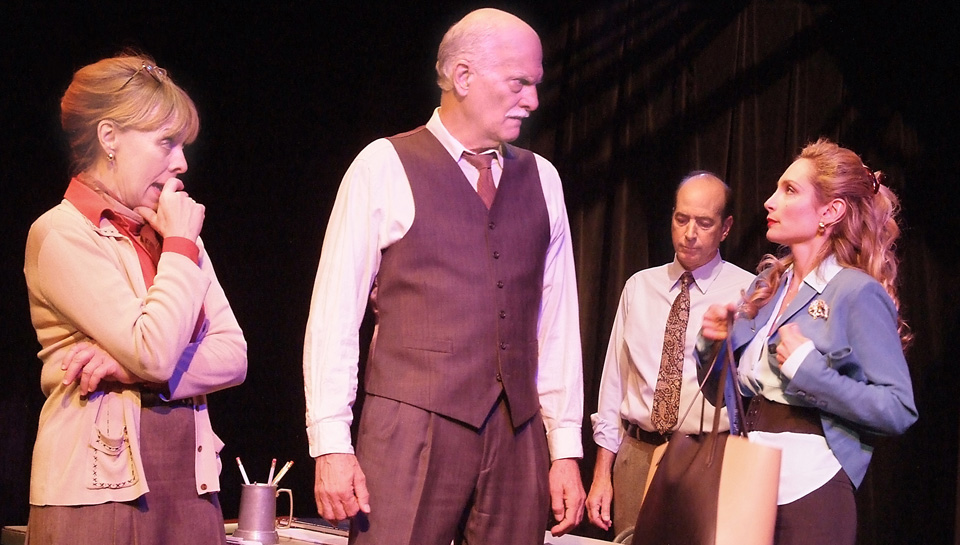

Other People’s Money (OPM), brilliantly directed by Oliver Muirhead for the Interact Theater Company, has a cast of five: Jorgenson (Kent Minault), risk-averse executive of Rhode Island-based New England Wire and Cable; Bea (D.J. Warner), his longtime assistant and now amatory companion; Kate (Robyn Cohen), Bea’s daughter and now an ambitious New York real estate attorney; Coles (Barry Heins), the company manager who feels stifled by Jorgenson’s antiquated business ways; and Lawrence Garfinkle (Rob Shapiro) — in the film it’s Garfield — one of the new predatory breed of adventurous corporate takeover raiders from New York (think Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital and the ilk described by Hightower above).

The origin of this play is fascinating and instructive: Sterner wrote it between 11 pm and 7 am while employed as a nighttime token clerk for the NYC Transit Authority. He based it on a small company he had invested in. It became the object of a takeover, and he sold his shares for a handsome profit. He decided to visit the company and found a ghost town. A once thriving business had been closed and used as a tax write-off. “I asked myself are we as a nation better off for restructuring?”

The play is about “five lives, the fate of a town, and whether or not decency will prevail over expediency,” says the director. “This electoral season forces us to see how the evolution of the American economy has created winners and losers, and…how we feel about that.”

OPM is about the seduction of money, and the unmitigated amorality of those who fetishize it. “I love money more than the things it can buy,” says Garfinkle, “but what I love more than money is other people’s money.” Could there be a more apt definition of the business model of a certain current presidential candidate? In fact, The Donald saw OPM and pronounced it “an extraordinarily insightful, timely, and witty play.” I couldn’t agree more.

This cast is absolutely superb in every respect. Eerily, as Kate, the foil opposite Garfinkle at my performance (the play is double cast), Robyn Cohen is the spitting image of the young crusading lawyer Hillary Clinton! It was deeply disturbing that the Garfinkle character is so clearly Jewish, not only in the portrayal but actually in the script, and yet to my eyes hasn’t a single redeeming feature (maybe why T found it all so charming).

In 1989 playwright Jerry Sterner was onto something very real happening in America, the disembowelment of manufacturing here and the outsourcing of jobs abroad, the same ideas Trump is cynically basing his campaign around. OPM is an amazingly prescient piece of art, entertaining to the max, and also deeply edifying and disturbing. Go out of your way to see this.

Vonnegut, USA runs through Nov. 20, playing Fri. and Sat. at 8 pm and Sun. at 2 pm at Atwater Village Theatre #2, 3269 Casitas Avenue, Los Angeles 90039. For tickets: http://vonnegutusa.bpt.me/, and for further information go here or call (323) 805.9355.

Other People’s Money plays Fri. and Sat. at 8 pm, and Sun. at 3 pm at the Pico Playhouse, 10508 W. Pico Blvd., Los Angeles 90064. The complete schedule of performances though Dec. 18, with their alternating casts, can be seen here. For more information and reservations: (818) 765.8732 or http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/2588643.