With the recent success of comic book characters on the big-screen – Avengers, Iron Man, Captain America, and Thor, just to name a few – is it any wonder there is an increased interest in comic books?

Unfortunately, missing from the comic book box-office bonanza are characters of color and, concomitantly, issues of race.

Yes, Samuel L. Jackson’s Nick Fury appears in the movies above – mostly as a post-credits tease to get movie goers excited about the Avengers, which eventually became a billion-dollar big-screen hit. However, even in the Avengers, Nick Fury has limited screen-time compared to his lighter skinned counter-parts, who do most of the fantastical heavy-lifting of world saving.

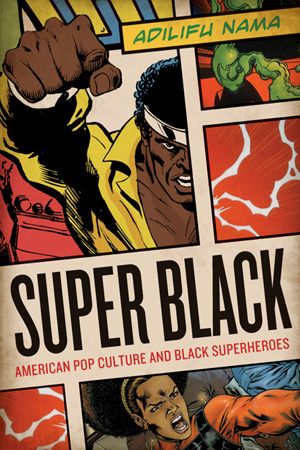

Adilifu Nama’s Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes does a great job of introducing many of today’s comic book fans with the history of African Americans in comic books and pop culture generally – something our current comic book-to-movie craze has failed to do.

Nama doesn’t just focus on African-American superheroes, he focuses on race relations in comic books generally and between comic book characters specifically. Additionally, his analysis of race as a plot device used to address larger political issues – like drugs, crime and the prison industrial complex – within a contextual framework makes clear the point that comic books aren’t just for kids.

For example, Nama credits Dennis O’Neil’s and Neal Adams’ Green Lantern co-starring Green Arrow as a comic book series that “dramatically recast superheroes, and shaped the superhero comic book as a space where acute social issues were engaged,” including racism.

In the Green Lantern co-starring Green Arrow inaugural issue (#76, 1979) titled “No Evil Shall Escape My Sight,” the superheroes confront American racism. Across several panels an elderly black man is depicted questioning Green Lantern’s commitment to racial justice: The elderly man says, “I been readin’ about you…How you work for the Blue Skins…and how on a planet someplace you helped out the Orange Skins…and you done considerable for the Purple Skins. Only there’s skins you never bothered with! The Black skins!” Then the man asks, “I want to know…how come? Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern!”

According to Nama, “Their conversation forever changed the boundaries of the superhero genre. Superheroes were no longer constrained to fighting imaginary creatures, intergalactic aliens, or Nazis from a distant past. Now they would grapple with some of the most toxic real-world social issues that America had to offer,” like racism.

Nama also places the creation of Black superheroes into historical context, and argues that many were by-products of specific political and ideological trends within the larger national and international movement for full equality and civil rights.

For example, Black Panther, who first appeared in Fantastic Four (#52, 1966) and is considered the first Black superhero in mainstream comics, is “a super-intelligent and highly skilled hunter-fighter superhero…” from a technologically advanced imaginary African Nation. In other words, he was “an idealized composite of third-world black revolutionaries and the anti-colonialist movement of the 1950’s that they represented…” While Black Panther initially appeared in Fantastic Four he eventually got his own comic book in 1977.

Similarly, Luke Cage, was a Black superhero that symbolized “the cresting prison reform movement of the early 1970s…” As a former gang member sent to prison for a crime he didn’t commit, Cage became a “victim of medical experimentation and prison violence at the hands of white authorities” and is considered “a very serious comic book superhero…who periodically takes on questionable assignments…” like chasing down Spiderman or working for Dr. Doom in order to pay the bills.

Unlike his white superhero counterparts – like Batman – Cage “struggles to ‘get paid.'” Undoubtedly, though he occupied a two-dimensional world, Cage was as a three-dimensional, complex comic book character. After 16 issues Luke Cage, Hero for Hire changed its title to Power Man, thereby articulating a connection to the 1960’s and 70’s Black Power movement.

Nama also addresses the preponderance of African Americans, or other people of color, as sidekicks. “Such representations,” he writes, “symbolize, promote and normalize their status as second-class citizens in American Society.”

While Nama also discusses movies and other forms of pop culture, Black comic books are his main focus.

Super Black is a short, yet illuminating analysis of Black Superheroes and race relations, primarily in the 2-D world. Obviously, at only 180 pages, it couldn’t cover all aspect of American culture and Black superheroes. However, as a short book, it does one hell of a good job.

Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes

Adilifu Nama

University of Texas Press, 2011, 180 pages

Available in hard cover, paperback and Kindle editions

Comments