The Taiwan question remains unresolved, more than 70 years after the end of the Chinese civil war. The U.S. stokes the fires of this divisive issue on a regular basis, keeping the government of the People’s Republic in Beijing on the defensive. The island remains a weapon in the West’s imperialist strategy of encircling and isolating China.

The recent visit by U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other members of Congress was just the latest in a long line of provocations. Such acts are intended to spark a response from China and then use that reaction to claim that China is supposedly being aggressive.

To understand why the island of Taiwan is so important to the mainland, we need to understand some history, the meaning of Taiwan island being China’s “internal affair,” the gradual development and deepening of ties across the Taiwan Strait, and how the issue might be resolved in the long-term.

History of the island of Taiwan

From the third to the seventh centuries, more and more people from the mainland settled on the island. By the time of the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368), administrative posts were established in Taiwan. In 1885, the Qing Dynasty fully integrated the island as a province of China.

This was not before the Dutch, at the dawn of European colonialism, occupied the island in 1624. After bitter struggles, the Chinese were able to expel the Dutch in 1662. The leader of the Chinese forces battling the colonialists was Zheng Chenggong, who is still regarded as a national hero in China today.

Next came the Japanese, who defeated a much-weakened Qing Empire in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. In one of many unequal treaties enforced upon China during the “century of humiliation,” Japan forced China to hand over Taiwan island and the Penghu islands (in the Taiwan Strait).

They remained Japanese colonies until the defeat of Japan in the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance—the anti-colonial struggle that merged into World War II—from 1937 to 1945. All of the occupied and colonized territories seized by Japan since the nineteenth century were returned, including the island of Taiwan.

Invasion launching point

Due to its strategic location, the island of Taiwan has been used many times in history as a base and launching point for invasions of mainland China.

Already in 1622-24, the Dutch colonizers used both Taiwan and the Penghu Islands to raid the mainland, trying to gain access to the ports in Fujian Province.

During the period of Japanese occupation (1895-1945), Taiwan became a crucial base for military incursions onto the mainland. Japanese planes, ships, and troops were based on the island due to its proximity to the mainland.

The Japanese did so during the infamous attack of the “Eight Nation Alliance.” In 1900, the U.S., U.K. (including troops from the Australian colonies), Germany, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Imperial Russia, and Japan invaded and captured Beijing.

Thousands of priceless artifacts, including irreplaceable manuscripts, were either destroyed or taken away as booty. Buildings were destroyed, indiscriminate slaughter took place, as well as the raping and bayoneting of women and children. This was a precursor to the Japanese “Rape of Nanjing” from December 1937 to January 1938, during which 300,000 Chinese civilians were massacred.

Japan was also using aircraft carriers during the 1937-45 conflict, and the term “unsinkable aircraft carrier” began to be used for islands like Taiwan.

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, Taiwan was returned to the mainland. Clearly, China sees any foreign power’s military presence on the island of Taiwan in light of this bitter history of invasion. It has experienced on too many occasions the efforts of imperialist powers to break up China.

Taiwan as an “internal affair” of China

Many will have heard of the oft-repeated statement that the Taiwan question is China’s “internal affair.” What does this mean?

In a general sense, “internal affair” refers to the simple fact that the mainland exercises what can be called an anti-colonial or anti-hegemonic sovereignty over all of China. Thus, for any other country to meddle in the situation is an infringement of Chinese sovereignty.

There is also a more specific sense: The Taiwan question is an unresolved part of the revolutionary struggle and civil war against the counter-revolution in China. From 1911 to 1949, the long revolutionary struggle had many twists and turns, resulting eventually in the liberation of China in 1949 and the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

However, some military and political personnel of the reactionary “Nationalist Party,” the Guomindang, led by Jiang Jieshi, or Chiang Kai-shek, retreated to Taiwan in defeat. Supported by the U.S., they armed the island and planned to use it as a base for returning to the mainland to take it over again.

It was internationally assumed at the time that Taiwan would soon be liberated as well. However, with the outbreak of the Korean War, the U.S. blocked the Taiwan Strait. The U.S. moved quickly to make Taiwan an outpost of its own military machine, stationing its 13th Air Force on the island.

This took place on June 27, 1950—two days after the outbreak of the Korean War—and the term “unsinkable aircraft carrier” came back into use. The U.S. thus reneged on post-WWII agreements and placed the island of Taiwan under its “protection.”

Thus, the revolutionary struggle and civil war are not yet over, and it is in this sense that the Taiwan question is China’s internal affair.

Closer ties built over decades

The basis for peaceful reunification of the mainland and Taiwan is the long-term development of deeper economic, social, and cultural ties. Outsiders are usually not aware of the fact that since 1979, the two sides have drawn ever closer.

It began with simple acts, such as direct postage and telephone connections. Most of the restrictions had been on the Taiwanese side, but gradually these barriers were lifted. In the 1980s, journalists from both sides began to travel, report, and set up offices for their news outlets in their respective territories.

By the 1990s, flights were operating via Hong Kong, although these became direct in the 2000s. Businesses and banks began to open on either side of the Taiwan Strait, families could visit relatives, and high-level talks began.

In the same decade, the Wang-Koo talks were held, initially in Singapore and then in Shanghai. Wang Daohan and Koo Chen-fu, leaders of the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS) and Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF), signed historic agreements for economic and people-to-people exchange. Many practical consultations followed, and the two associations met once again, under new chairs, in 2008 in Taiwan.

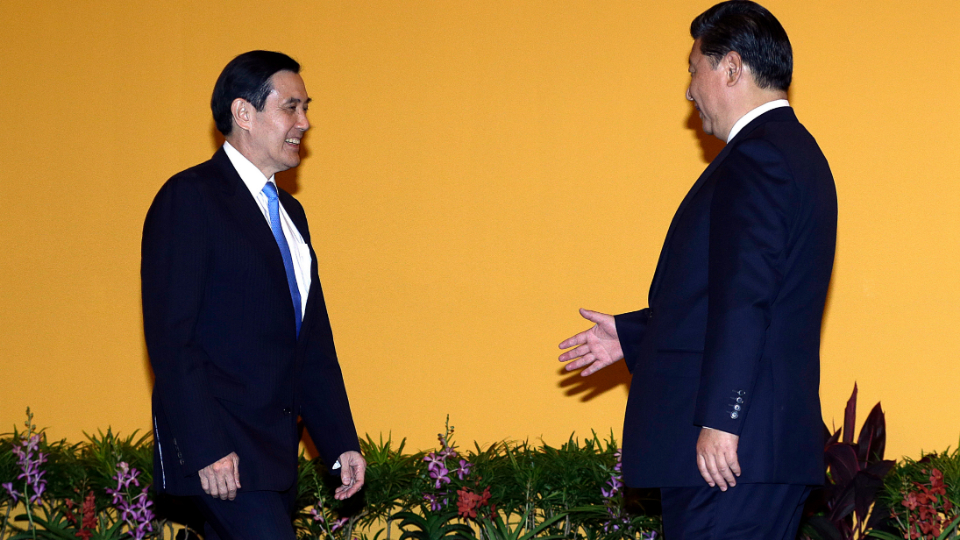

In November 2015, Xi Jinping, leader of the Communist Party of China, and Ma Ying-jeou, leader of the Guomindang, met in Singapore. This was the first meeting between the top leaders of the two sides since the war between them concluded in1949.

Clearly, there has been a gradual and ever-deeper development of relations as a foundation for reunification—despite US-led efforts to disrupt the process.

It is in this light that we should understand the last-ditch effort by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), another political party in Taiwan, to promote separatism. Since it managed to become the main force in the Taiwanese government in 2016, it has tried to disrupt the trend towards reunification.

Resolving the Taiwan question

While simple on paper, the resolution of the Taiwan situation has proven immensely difficult. The following are the key points:

- Capitalist countries need to abide by their agreements. Already in 1943, the Cairo Declaration observed that “all the territories that Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Taiwan and Penghu Islands, shall be restored” to China. The Cairo Declaration included the U.S., U.K., and China. In 1945, the Potsdam Declaration stated that “the terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out.”

- In 1972, 1979, and 1982, China and the U.S. signed three communiqués, observing that “The United States acknowledges that all Chinese people on both sides of the Taiwan Strait agree that there is but one China and that Taiwan is part of China.” The later communiqués also agreed to keep contact with Taiwan at an unofficial level and reduce arms sales to the point of abolishing them altogether.

- Unfortunately, as the Chinese side—among many others—knows very well, the U.S. was not to be trusted.

- The Taiwan question should be resolved by the Chinese people on both sides of the strait. The current unstable situation is the result of an incomplete process of revolutionary struggle and civil war, as well as the ever more desperate measures by imperialist powers to use Taiwan as a lever to destabilize the mainland. Resolving this problem is up to the sole legitimate government of China in Beijing and the Taiwan authorities.

- The principles which provide an outline are “peaceful reunification” and “one country, two systems.” Late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s innovative and dialectical materialist proposal of “one country, two systems” was developed with Taiwan (and Hong Kong) in mind.

Contrary to the way it is sometimes depicted, the “system” refers to the socialist economic system in China and the capitalist economic system in Taiwan. The “one country” refers to China as a whole. The proposal has immense flexibility, so much so that initially Taiwan would be able to keep its economic, political, and even military structures. This would be a “high degree of autonomy,” but not complete autonomy.

The overwhelming desire among common people on both sides is for eventual peaceful reunification. This was in fact the trend until 2016, with even the Guomindang on Taiwan island coming to see the need and benefits. All that is blocking the way is the rearguard action of the island’s DPP and the interference of U.S. imperialism.

The Guardian (Australia)