WASHINGTON—If you want to know why approximately 100,000 farm workers could be at risk of illness or even death—depending on whether and how well their bosses protect them—here’s your answer: A new strain of avian flu is developing in the U.S.

If you want to know why the price of eggs has soared, here’s your answer: That avian flu.

If you want to know what may be next on that list, try the price of beef. Or the price of chicken.

If you want to know what union is blowing the whistle on the threat of avian flu, the answer is the United Farm Workers.

And if you want to know the government’s response to this latest potential pandemic danger, the answer is: Spotty at best with unproven claims that there is no danger to the public. There is no explanation as to why 100,000 farm workers are not included in the “public.”

Welcome (?) to what may be the next pandemic to hit the U.S., even if it is too early yet to say. And welcome to the responses, or lack of them, from governmental and especially corporate actors who are supposed to put people before profits, but don’t.

Three federal agencies recognize the risk but they want bosses and workers to take voluntary actions to protect themselves, minus federal mandates. All three—the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Centers for Disease Control—are concentrating on protecting humans from some of the sick cattle, but not from the sick birds which are the source of the rising infections.

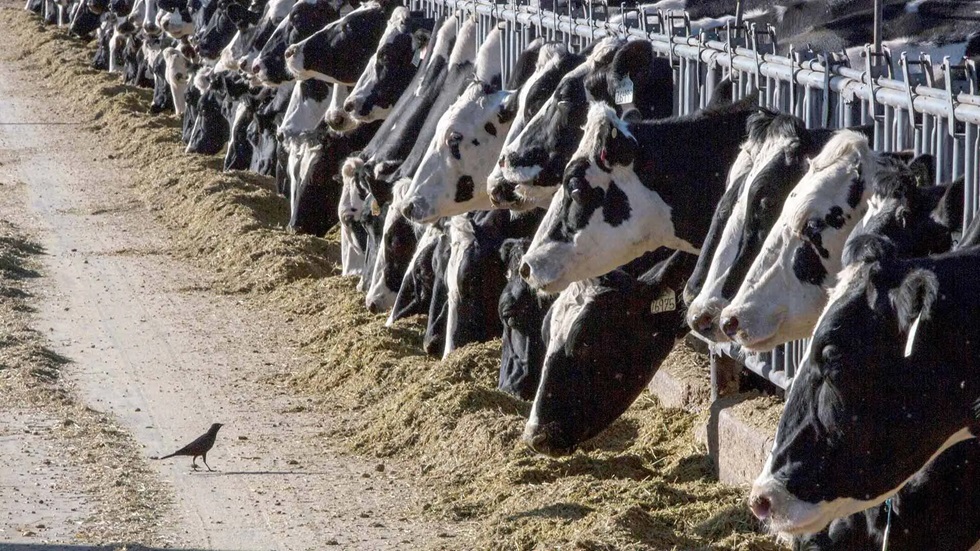

And if you want to know why workers are at risk from this avian flu virus, H5N1, the answer, the United Farm Workers say, is corporate greed of the oligopoly of beef production firms and unsustainable chicken farms too. It was only a matter of time, environmentalists say, that profit-driven production methods of chicken and eggs in hellish conditions for animals that spoil the environment and harm humans too would eventually result in disease threatening thousands and perhaps even millions of people.

The union explains the avian flu threat to people could be magnified because the few unorganized non-union workers who are tested and test positive for the flu have to come to work or lose their pay or their jobs.

Lack of a union contract

Those farm workers lack the health and safety protections of a union contract, which could let them stay home to recuperate. They’re paid so little they have to work every day, sick or not, to feed their families. And if they come in sick, they endanger their colleagues. And that endangers people in their families and communities when they go home, and that endangers the broad general public. This is exactly what happened with COVID when workers at pork plants became infected and carried the disease home to their communities, eventually shutting down the entire country. We’ve been here before.

Many of the 100,000 farmworkers now in danger are migrants who don’t speak English, but either Spanish or a language, such as the Mayan languages of Tzeltal and Tzotzil, native to their origins in Latin America. For them, even Spanish instructions on how to combat the threat of avian flu may not be understandable.

“For farmworkers specifically, certainly these are folks that are living in a state of economic desperation, and what they’re not going to do is, they’re not going to test for something if they don’t have paid sick leave, because they cannot afford to be sent home and told to stay home and not work,” Elizabeth Strater, UFW’S director of strategic campaigns, said.

As you might expect, avian flu is prevalent in birds, especially wild birds. Worldwide, when it hits them the mortality rate is 90%-100%, scientists report. This latest H5N1 strain of avian flu erupted in Asia three years ago before starting to spread. The first eight cases in the Los Angeles-Long Beach area, for example, were among wild birds—seven Canadian geese and a night heron—in September 2022, Random Lengths News reported that October.

Since then, avian flu migrated to Texas and infected cattle, and one human, a farm worker in the panhandle several dozen miles from Amarillo. And infected Texan cattle were flown to other states and farms, in Michigan, Idaho, and Kansas. Cattle there became infected, too. Infected birds, however, have been found in most of the 50 states.

Avian flu “spreads through direct bird-to-bird contact or indirectly when the virus is on clothing, footwear, vehicles, rodents, insects, feed, water, feathers, etc. Birds shed the virus in bodily fluids such as respiratory droplets, mucus, saliva, and feces,” local public health officials tell us.

People sicken “when the virus is inhaled in droplets or dust, or when the viruses enter people’s eyes, nose or mouth through unprotected contact with infected birds, including chickens, or contact with contaminated surfaces.”

The Texan farm worker caught avian flu on March 25 from sick cows. Authorities claim five days of antibiotics cleared up its impact on him: The worker developed a severe case of conjunctivitis, more commonly known as pink eye. He’s one of only 24 confirmed human avian flu cases worldwide since the start of 2021, the World Health Organization says. Its symptoms are different in different people, just like those of the coronavirus. They range from mild and moderate to severe.

But back to the birds, the chickens, and the eggs.

Just since mid-March the H5NI avian flu virus has hit U.S. chickens, producing a mass slaughter of two million infected chickens by the nation’s largest egg producer, Mississippi-based Cal-Maine Foods—and a drastic drop in egg production. Cal-Maine had to close its biggest factory farm, in Palmer County, Texas, and later had to close a second plant in Michigan.

The Texas plant closed a week after the farm worker became ill. The slaughter wiped out 3.6% of Cal-Maine’s total chicken flock, which supplies supermarkets from the Pacific Coast through the Great Lakes. Walk into some supermarkets in Chicago, and you’ll find eggs selling for $6 or $7 a dozen.

Continues to work “closely”

In a prepared statement to National Public Radio, Cal-Maine said it “continues to work closely with federal, state, and local government officials and focused industry groups to mitigate the risk of future outbreaks and effectively manage the response.”

“Sick birds causing sick cows resulting in a sick person,” the Santa Barbara (Calif.) Independent summarized in early May. “The sequence may feel like a harbinger of COVID-19 all over again, but health professionals believe the avian flu, or H5N1, is very different from what was first dubbed a ‘novel coronavirus.’

“This time, it is dairy cows that are getting infected, which could add to the struggles of milk and beef suppliers.

“This one is not a ‘novel’ virus,” the county’s chief medical officer told the paper. “It has been found in birds for decades.” A century is more like it: Scientists and disease historians report this avian flu virus is a descendant of the misnamed “Spanish flu” of 1918-20.

That plague, which killed 50 million people worldwide, actually started among U.S. Army soldiers in Fort Riley, Kansas.

After this year’s infected cattle outbreaks in Kansas, Idaho, Michigan, and Texas, factory farmers and big food processors started to cull cows for avian flu. Fewer cows led to slaughter equals higher beef prices at the grocery store.

That’s because the beef processing industry, like so much else of agribusiness, is now in the hands of an oligopoly of a few firms, who can collude at will to fix prices for products. That corporate greed covers chicken and egg producers, too.

As the Federal Trade Commission, which investigates and sometimes prosecutes oligopolies, points out on its website, it has to spend most of its money probing “certain segments of the economy where… consumer spending is high.” That includes food. (The oligopolies often collude on fixing workers’ wages, too, FTC Chair Lena Khan has said.)

The Texas farm worker’s illness and its cause, the cattle, led the Food and Drug Administration to test 36 cattle herds in nine states, Dr. Amesh Adalja of Johns Hopkins University said. And 220 farm workers have taken voluntary tests for the avian flu. No results have been reported yet.

The FDA also tested 297 pasteurized retail dairy products, such as cottage cheese and sour cream, from 38 states after previous findings showed fragments of the virus got into the commercial milk supply, Adalja added. Pasteurization neutralized the fragments’ potency. And FDA tested powdered infant and toddler formulas for the virus and found no avian flu.

Meanwhile, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is actively encouraging poultry plants and beef slaughterhouses to arm their workers with personal protective equipment (PPE), train them how to don and doff it and develop plans to combat the avian flu.

Same strategy with COVID

In other words, the same strategy OSHA pushed to combat the coronavirus. It tried a mandate then, but the right-wing majority on the U.S. Supreme Court shot it down.

And Democratic President Joe Biden’s Agriculture Department will dole out $98 million to cattle farmers over the next four months to pay workers to get tested for avian flu, isolate sick cows from the herds, pay for veterinarian visits to treat sick cows, and to supply PPE to workers.

USDA will also use part of the money to help farmers safely dispose of infected milk waste through a heat treatment. And Biden will earmark $93 million to the Centers for Disease Control to analyze virus mutations and increase testing for the virus at public health labs.

But neither agency is mandating testing of workers for avian flu, and some states, again notably Texas, resist letting federal inspectors come onto farmers’ lands and into slaughtering plants. The Agriculture Department retorts the inspectors should come in. The CDC adds there’s an effective anti-flu vaccine that lets humans successfully battle this avian flu virus.

The World Health Organization also minimizes the impact of the potential avian flu pandemic, just as it did at the start of the coronavirus plague.

That’s though the CDC says “the wide geographic spread of H5N1 viruses in wild birds, poultry, and some other mammals, including in cows, could create additional opportunities for people to be exposed to these viruses.” Reports show “some other mammals” with the virus include Alaskan polar bears.

“CDC believes the current risk to the general public from bird flu viruses is low.” But “there could be an increase in sporadic human infections resulting from bird and animal exposures, even if the risk of these viruses spreading from birds to people has not increased. People who have job-related or recreational exposure to infected birds or animals, including cows, are at greater risk of contracting the virus.”

Starting April 29, the Agricultural Department’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service required “mandatory testing prior to the interstate movement of lactating dairy cattle and mandatory reporting of positive influenza test results in livestock.” It claimed its actions would “address any risks to animal health, public health, and the safety of our food supply.”

“To help producers enhance their biosecurity practices, USDA is offering additional support for producers who confirmed positive” avian flu findings in “dairy herds so they have tools to eliminate the virus and can protect their animals, themselves, their families, and their employees,” APHIS added.

Translation into English: Federal money.

USDA will distribute $98 million to the dairy farmers over the next four months to encourage their workers to be tested for avian flu, to reimburse the farmers for veterinarians’ costs for treating sick cows, and to administer the Food and Drug Administration-approved heat treatment that kills the virus in milk waste.

Distribute diagnostic kits

Second translation: $93 million to the CDC to make and distribute avian flu diagnostic test kits, to analyze the virus to track mutations, to start a contact tracing program and to help public health clinics increase avian flu testing. “We need to continue to prepare for the possibility” the avian flu virus “might jump to humans,” Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Robert Califf told senators.

The National Milk Producers Federation, also known as the dairy lobby, is going along with the avian flu testing, which, however, isn’t mandatory on dairy farms themselves—only when lactating cows are shipped from, say, Texas, to Michigan. It thanked the feds “for effectively using existing authorities to offer necessary assistance for dairy farmers as they meet the challenges of H5N1 in dairy cattle.” Translate the words “necessary assistance” into the word “money.”

“Care for farm workers and animals is critical for milk producers, as is protecting against potential human health risks and reassuring the public,” the lobby’s president’s statement added.

But while Biden administration agencies take the avian flu outbreak among cattle seriously, it’s speaking less so far about the avian flu threat from birds, such as chickens.

All this sounds like the initial response to the coronavirus, but on a smaller scale, until you remember that the New York Times estimates that up to 100,000 dairy workers risk illness or death from the avian flu.

That happens to be the same number of U.S. people the coronavirus killed before the Republican Trump regime started to take the fight against that modern-day plague seriously, according to public health specialist Dr. Deborah Birx, then a White House adviser on the coronavirus.

The following one million U.S. coronavirus deaths, Birx said publically, were needless. Trump ostracized Dr. Birx for telling the truth.

And just like the response to the coronavirus, there is at least one simple measure people can take to protect themselves against avian flu, public health researchers say. For the coronavirus, it was wearing masks and distancing—six feet from the next person if you’re standing in a line, for example.

For this virus, it’s wearing PPE masks if you work around birds or cattle, alive or dead. And, for everybody, to drink only pasteurized milk.

What’s the threat if you don’t? Well, Fox Health News reported on a test in, again, Texas, on 24 cats drinking the raw unpasteurized milk containing the virus.

All the cats became ill within two or three days. Half recovered. The other half died.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments