(Editor’s note: Cuba has been nominated to receive the Nobel Peace Price for its health care efforts around the world and for fighting Ebola in West Africa. Click here for a petition to publicize the nomination.)

Health care for Cubans and the care Cuba extends to the world have gained high praise. For 50 years, Cuba’s health care reforms have been the basis for health care planners and providers to be able to extend medical care, medical education, and disease prevention throughout the world.

1. Health Care in Cuba

Numbers and narrative alike tell the story of a health care project comprehensive, effective and accessible to all Cuban people. Actual health care in Cuba and public health are identical — for U.S. health care planners, separate entities. Both the community and individual are at once objects of care in Cuba. Payment for care is not an individual responsibility. Cuba has emphasized provision of health facilities, services, and practitioners to rural areas in response to deprivations there prior to the Revolution.

Health authorities have emphasized data collection, prevention strategies, health education for all, biomedical research, and medical-education capabilities. Cuba has devised full-spectrum health care, from specialty hospitals for complicated and unusual illnesses, to mid-level centers providing consultations, emergency care, and laboratory services, to thousands of family doctor-nurse teams providing first-contact care in rural areas and crowded cities alike. In developing their system of care, health care leaders frequently have resorted to improvisation, taking advantage of innovative examples elsewhere.

Article 50 of Cuba’s revised 1976 Constitution proclaims that, “Everyone has the right to health protection and care.” Political commitment is what drives planning. In 1965, Fidel Castro led 475 new doctors, the first to be educated under the Revolution, to the summit of Pico Turquino, Cuba’s highest mountain. There the students vowed “to expand rural medical services, to promote preventive health care among the population and to providing selfless aid to needy peoples.” Describing “Revolutionary Medicine” to a group of soldiers in 1960, Che Guevara established the duty of the state, “to provide public health services for the greatest possible number of persons, institute a program of preventive medicine … and to orient the creative abilities of all medical professionals toward the tasks of social medicine.”

The role of political leadership was clear in 1983 when Fidel Castro urged specialists at Cuba’s principle infectious disease institute to make certain that the oncoming HIV/AIDS epidemic “does not constitute a health problem for Cuba.” Thus preventative measures were already in place when Cuba’s first case of the disease was diagnosed two years later. Infection rates are still the lowest in the region.

Data from the World Health Organization and Pan American Health Organization confirm Cuba’s own figures on health outcome. Estimates of infant mortality rates (IMR) during the 1950’s, prior to the Cuban Revolution, vary widely, from 65 babies dying in their first year of life (out of 1000 births) to 39 infant deaths (in 1960). Life expectancy at birth was 64 or less, according to varying tallies. Cuba had one medical school, eight small nursing schools, and 6286 practicing and teaching physicians, two thirds of whom were based in Havana. Within two years 3000 physicians would leave for foreign exile.

Data from the World Health Organization and Pan American Health Organization confirm Cuba’s own figures on health outcome. (3) Estimates of infant mortality rates (IMR) during the 1950’s, prior to the Cuban Revolution, vary widely, from 65 babies dying in their first year of life (out of 1000 births) to 39 infant deaths (in 1960). Life expectancy at birth was 64 or less, according to varying tallies. Cuba had one medical school, eight small nursing schools, and 6286 practicing and teaching physicians, two thirds of whom were based in Havana. Within two years 3000 physicians would leave for foreign exile.

In 2013 Cuban life expectancy was 78.5 years (79 in the United States). Cuba’s 2014 IMR was 4.2. The U. S. rate in 2011 was 6.1 and is unchanged since, with black infants dying at twice that rate. (The IMR for Canada was 4.8 recently – 15.7 for all of Latin America.) Cuba’s rate of child deaths under age five, per thousand births, was 5.7 in 2014; the most recent U. S. rate was 7.1. Cuba has recently spent 10 percent of its GDP on health care; the United States 17.6 percent; Canada 11.4; and the UK 9.6 percent. Cuba has one physician for 149 persons, 85,563 in all; the U. S. rate is one per 413 persons. Cuba, with 24 medical schools, graduated more than 10,000 physicians in 2013; the United States graduated 18,154 that year.

Cuban health care extends to biomedical research and production, also export of multiple vaccines, diagnostic test kits, and generic drugs – including anti-HIV agents. That sector has prioritized immunotherapy products and anti-cancer vaccines. “In one section of Havana,” an observer notes,” there are 24 research and 58 manufacturing facilities, employing some 7000 scientists and engineers, and [that] accounted for $711 million (USD) in export earnings in 2011.” (4) Cuban scientists have developed innovative products, among them: interferons, a vaccine against Type B meningococcal meningitis, a drug directed at foot ulcers caused by diabetes, recombinant streptokinase used for myocardial infarctions, and epidermal growth factor helpful in the treatment of burns.

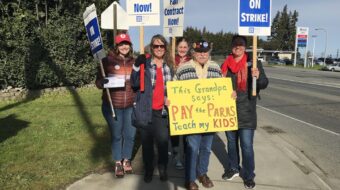

2. Cuban International Medical Solidarity

It started in 1960. Cuba sent a relief team of health workers to Chile after an earthquake there. They went to Algeria in 1963 to establish a public health system. Since then, according to Professor John M. Kirk of Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, over 325,000 Cuban medical personnel have provided assistance in 158 countries. (5) Indeed, the Cuban Constitution refers to “proletarian internationalism, brotherly friendship, help, cooperation, and solidarity with the peoples of the world.”

Kirk believes that, “Cuba has provided an example for the planet, showing how its successful medical collaboration programs have been far more successful, and more far-reaching, than anything provided by all of the G-8 countries’ efforts combined. For over fifty years Cuban medical personnel have served the poorest and most neglected areas of the world, going where other doctors refused to go. At present they are looking after the well-being of some 70 million people.”

He adds that, “As of January 2015 there are 51,847 Cuban medical personnel (of whom 50.1percent are physicians) working in 67 countries-mainly in the developing world … [I]n Africa over 4,000 medical personnel are working in 32 countries” The situation, he says, is comparable to “having 223,000 US doctors serving in developing countries.”

Some notable examples:

- Cuban medical teams went to Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1970’s in conjunction with anti-apartheid military actions there.

- Beginning in 1990 Cuba developed comprehensive medical-care programs centered in Tarará, Cuba, for the 21,874 children and 4,240 adults who were victims of the 1986 nuclear disaster in Chernobyl, Ukraine. Cuba provided medical care and provisions at no cost.

- During the 1990’s, disaster relief efforts culminated in help given to Haiti and Central American countries following Hurricanes George and Mitch in 1998. The latter took tens of thousands of lives.

- Hundreds of Cuban doctors remained in Haiti and were there when the disastrous 2010 earthquake occurred. New physician arrivals took the lead in providing care and rehabilitation for injuries and responding to the cholera epidemic that followed. They stayed; currently 700 Cuban doctors are working in Haiti. In all 11,000 Cuban health workers have served there since 1998.

- Cuban doctors have cared for patients in East Timor since 2003; 350 were there in 2008, and four years later hundreds of that country’s young people were training as physicians in Cuba, also in an East Timorese medical school established and staffed by Cubans.

- From 2004 on, as part of “Operation Miracle,” Cuban eye surgeons with logistical support from Venezuela have performed sight-restoring surgery, mainly for cataracts and glaucoma, for 3.4 million patients in 31 countries.

- In 2005 in Pakistan within two weeks of an earthquake that killed 250,000 people, over 3000 Cuban medical personnel were caring for the injured in 32 field hospitals, in the snow and mountains. They stayed for six months.

- Earlier that year Cuban disaster-relief teams working abroad became the “Henry Reeve Brigade,” named in honor of a young U. S. soldier who joined rebel forces in Cuba’s first War for Independence. Some 1500 Cuban doctors preparing to go to New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina – The U. S. government turned them down. – were the first contingent to be so designated. By that time 36 disaster relief teams had already worked in 24 countries.

- In late 2014, 251 Brigade members traveled to East Africa to combat the Ebola epidemic. Recruited from 15,000 volunteers, they stayed for six months. For its anti-Ebola contribution, Norway’s Conference of Trade Unions in February 2015, nominated the Henry Reeve Brigade for the Nobel Peace Prize.

- “Brigade 41” of the Brigade, with 49 health workers, arrived in Katmandu, Nepal, in May 2015 to deal with suffering caused by a major earthquake. This was the 41st mobilization of the Brigade since its formation in 2005.

- In August 2015, 16 Cubans – physicians, nurses, and epidemiologists – were on the Caribbean island of Dominica helping victims of flooding caused by Hurricane Erika. They brought 1.2 tons of medical supplies and provisions.

- Since 2005, Cuban physicians, usually from 12,000 to 15,000 at a time, have served in Venezuela as practitioners and medical teachers. In return, Cuba gains an assured, reasonably priced supply of Venezuelan oil.

- Some 11,000 Cuban physicians, the majority of them women, have been working since 2013 in underserved areas of Brazil, whose government reimburses its Cuban counterpart.

Medical education is a big part of Cuban medical internationalism. Kirk reports that in Africa, for example, 5,500 Cuban professionals were working there in 2012, and also that “40,000 Africans have graduated from Cuban universities and there are currently 3,000 studying in Cuba.”

Cuba has established medical faculties in 15 countries and provided teachers for 13 of them. According to journalist Salim Lamrani, Cuba annually provides training in medicine, nursing, or medical technology for some 29,000 students from over 100 foreign countries. (6) Every year half of Cuba’s medical graduates are foreign students. Cuba-Venezuela cooperation has resulted in some 25,000 Venezuelans now studying medicine under Cubans’ tutelage as part of an innovative program that has students studying in their own communities. Kirk reports that Cuban teachers have helped train “more than 80,000 midwives, 65 health promoters and 3,000 nurses” in developing countries.

The jewel in the crown of Cuba’s overseas medical work is the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM). Formed in 1999, the Havana-based institution, which utilizes teaching hospitals across the island, provides medical education at no personal cost to students who arrive from Africa, Latin America, Asia, and from the United States – almost 100 counties in all. Up to 1500 students graduate from the School every year and, as of August 2015, some 23,000 physicians have returned to their own countries, where, as promised, they will be serving where they are most needed. United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, visiting the School, told students, “ELAM does more than train doctors. You produce miracle workers.”

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Cuban health care relates to the community orientation of practitioners and teachers alike, in Cuba and abroad.

Kirk quotes El Salvador’s Public Health Minister María Isabel Rodríguez: “The Cubans treat them [their patients] as individuals, recognizing their human quality, and spending time with them. Their medical treatment is different – the Cuban doctors respect their patients and listen to them.”

Kirk suggests that patients “are not seen as suffering from a singular ailment … instead they are viewed in the wider bio-psycho-social context.” And, “the system is based upon medical training in which ethical considerations and the responsibilities of professionals are emphasized far more than in medical schools of the industrialized world. … The result is that the Cuban system has developed a cost-effective, pragmatic, highly ethical and sustainable system of public healthcare.”

In January 2015 Professor Kirk wrote to the Norwegian Nobel Committee indicating he was “delighted to nominate the Cuban medical internationalism program for the Nobel Peace Prize.” Ban Ki-moon would concur: Cuban “doctors are with communities through thick and thin – before disasters strike … throughout crises … and long after storms have passed. They are often the first to arrive and the last to leave.”

Photo: Cuban health worker wearing protective gear. | telesurv

Comments