Despite the yearly celebrations of Martin Luther King Day and African American History Month, it is probably little known what the great freedom fighter had to say about the horrific mistreatment of Native Americans by the U.S. In his 1963 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” writing about the origins of racism in this country, King strongly condemned the historic injustices inflicted on Native people. He wrote the following:

“Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shores, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. From the sixteenth century forward, blood flowed in battles of racial supremacy. We are perhaps the only nation which tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out its Indigenous population. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it.”

Woefully, Dr. King’s words still ring true to this very day in so many respects. But King’s poignant words on the tragic history of Native Americans are largely unknown in mainstream society.

Although King played the leading role on the cutting edge of the African American liberation struggle for social justice and equality, he was a fighter for all of the oppressed of this land. His birthday holiday this year brought to mind a story I was told years ago of how he assisted Native people in south Alabama in the late 1950s.

At that time the Poarch Band of Creek Indians were trying to completely desegregate schools in their area. The South has so many seemingly outlandish racial problems: In this case, light-complected Native children were allowed to ride school buses to previously all white schools, while dark-skinned Indian children from the same band were barred from riding the same buses.

Tribal leaders, upon hearing of King’s desegregation campaign in Birmingham, Ala., contacted him for assistance. He promptly responded and through his intervention the problem was quickly resolved.

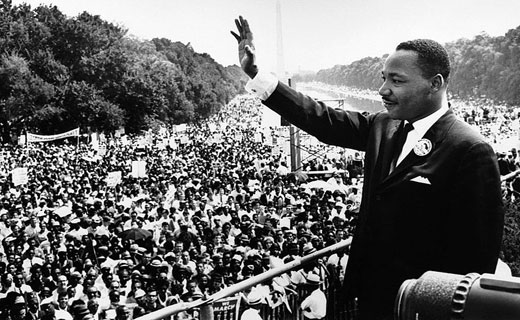

Also, little known is that in the 1963 March on Washington there was a sizable Native American contingent, including many from South Dakota. Moreover, the civil rights movement inspired the Native American rights movement of the 1960s and many of its leaders. In fact, the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) was patterned after the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Re-reading Dr. King’s words I had to harken back in history to the fact that according to U.S. Census Bureau figures, by 1900 there were only 237,196 Native Americans left in the entire country – this from an original population that numbered in the tens of millions. In the words of one historian the outright massacres had ceased by then, simply “because there were just not that many Indians left to kill.” King rightly concluded that the genocide of American Indians was “national policy.” Indeed, on many reservations the story still circulates that as late as the 1890s a debate was held by the U.S. Congress to consider the outright military extermination of all remaining Native Americans. According to these accounts the only reason this nefarious plan was not carried out was because it would be too expensive.

But fast forwarding to the 21st century it must be seen that both the civil rights movement and the Native American rights movement have had a major impact on the U.S. and the world at large. Dr. King played an immeasurable role in these movements that roiled the status quo and marked a new stage of struggles that are ongoing to this day.

Photo: Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial where he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington. Wikimedia Commons

Comments