War in Honduras pits the powerful few against the many. Their lives are precarious and seemingly disposable. On October 18 in Bajo Aguán assassins shot and killed José Ángel Flores, president of the Unified Peasant Movement of Aguán (MUCA), and Silmer Dionisio George, another MUCA leader.

MUCA defends the right of 3500 families to land they farm cooperatively in Bajo Aguán in northeastern Honduras. Prior to President Manuel Zelaya’s forced departure in 2009, efforts by his government to implement earlier land reform measures had emboldened them to occupy disputed land.

Corporations, notably the Dinant group, grow prodigious amounts of African palm in Bajo Aguán. Controlling 55,000 acres in 2011, Dinant produces palm oil for its own multi-national food processing empire and sells oil in Europe and the United States for use in industrial products and biofuels. Before he died in 2015, billionaire owner Miguel Facussé notoriously relied on paramilitary violence to eject small farmers occupying land claimed by Dinant.

The two recent murders and the assassination March 3, 2016 in La Esperanza of Berta Cáceres epitomize the deadly consequences of resisting wealthy conglomerates, especially when the Honduran and U. S. governments are on their side.

Award-winning environmentalist Cáceres founded and led the Civic Council of People’s and Indigenous Organizations (COPINH). At her death she was campaigning to end construction of a dam across the Gualcarque River. For Cáceres, the river was sacred to her own Lenca people, and obstructing its flow posed dire environmental consequences.

Agitation under her leadership had already caused a Chinese corporation associated with the Honduran dam – builder to abandon a project aimed at building four dams. And the World Bank withdrew its funding.

Appreciation of how these murders relate to popular struggle requires awareness of a painful history and now social disaster; income disparity among Hondurans is the widest in Latin America and ranks sixth in the world; poverty afflicts 64.5 percent of households there.

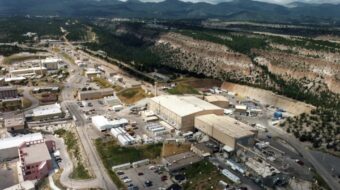

And, proliferation of mining and hydroelectric ventures accompanies corporate land-grabbing as practiced in Bajo Aguán, all under the auspices of international corporations. The effect throughout Honduras has been rural lives becoming unsustainable and displacement of people from small land holdings. The Honduran government since 2009 has approved some 300 hydroelectric projects and at least 870 mining projects. National and transnational companies now enjoy concessions applying to 35 percent of Honduran land.

Many in resistance die. Thugs, presumably paramilitaries, have killed 150 farmer activists in Bajo Aguán since 2009. Over the past decade “114 ecological militants” have been killed throughout Honduras. Or, according to another report, 101 environmental activists were killed between 2010 and 2014; 40 percent of them were indigenous. Tomás Membreño, Berta Caceras’ successor as head of COPINH, barely escaped a recent assassination attempt; five other anti-dam protesters have been killed since her death.

Reacting to Cáceres’ murder, World Bank President Jim Yong Kim rationalized, “You cannot do the work we´re trying to do and not have some of these incidents happen.” A MUCA press release specified that, “units under the command of U. S. Special Forces beginning in 2010 undertook a series of training operations with Honduran special forces units at the [U. S. – financed] Río Claro military base” in Aguán. And, paramilitaries in the area “use arms that only the state possesses.”

Political repression has mounted following the 2009 military coup that removed President Manuel “Mel” Zelaya. U.S. academician Dana Frank claims that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton promoted regional acceptance of the coup and thereby “opened the door to this … almost complete destruction of the rule of law in Honduras.”

Zelaya currently leads the social democratic Libre Party that might have scored a victory in the 2013 presidential elections. However, fraud and other irregularities steered votes toward Nationalist Party candidate Juan Orlando Hernández. For U. S. ambassador Lisa Kubisk, the voting was a “transparent process.”

These realities, taken together, set the stage for the assassinations of José Ángel Flores, Silmer Dionisio George, and Berta Cáceres. As Cáceres explained in an interview before she died: “Indigenous peoples are confronting a hegemonic project pushed by big national and international capital … The promoters of that strategy have imposed a profoundly neoliberal model based on invasion and militarization of territories, plunder, and privatization of resources.”

Meanwhile, indigenous groups were peacefully demonstrating October 20 in Tegucigalpa. They were calling for an “impartial investigation” of Berta Cáceres’ murder, cancelation of the Agua Zarca dam, and demilitarization of their areas. True to form, the U. S. – supported Honduran state used militarized police to brutally disperse the protesters. Some required hospital care.

Comments