Shane Bauer, writing for Mother Jones, gives us a glimpse into the grotesque conditions at the Winnfield private prison in Ohio: “At 6:30 in the morning, the air is so saturated with pepper spray that tears stream down my face. The key officer is doing paperwork in a gas mask. A man screams and flails naked in a shower, his body drenched with pepper spray. Cockroaches run around frantically to escape the burning.”

In the same piece, Bauer tells a story of a man who is found by panicked inmates lying on his bed clutching his chest and nearly passed out. He’s hauled to the infirmary on a stretcher, where he describes a throbbing pain in his chest. “They told me I got fluid in my lungs,” he says, “and they won’t send me to the hospital.” He would not be sent to the hospital because the for-profit prison deemed it too expensive for an inmate who only brought in $34 a day.

These are the conditions and the stories that private prisons breed. They are what led Attorney General Sally Yates, under the Obama Administration, to direct the prison bureau to decline to renew or substantially reduce the scope of existing private prison contracts, citing their poor performance compared to federal prisons. Under Trump, Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded that directive.

In his first month in office, President Joe Biden signed an executive order to restore Sally Yates’s directive and phase out the federal government’s use of private prisons. It instructed the attorney general to decline to renew federal contracts with privately-owned detention facilities. In its preamble, the executive order recognizes the reality of mass incarceration in the United States, how it disproportionately affects people of color, and the great costs and hardships it imposes on our society. The executive order proposes that the federal government phase out its use of private prisons, not just to remove the profit incentive to incarcerate people, but also because private prisons have failed to rehabilitate incarcerated individuals and allow them a fair chance at reintegrating back into their communities.

While the executive order does not do enough to live up to the lofty goals laid out in its preamble (as this piece discusses below), it is an important step forward toward reducing mass incarceration and abolishing the private prison industry.

The war on drugs and harsher sentencing laws in the 1980s and 1990s led to a flood of incarceration and, in turn, the rise of private prisons to accommodate the rapidly growing prison population. The private prison industry grew an incredible 1,600% from 1990 to 2005. But private prisons have produced worsening conditions for prisoners. Private prisons are not held to the same rules and regulations as facilities run by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Their emphasis is on extreme cost-cutting. They pay their officers less and have a higher inmate-to-officer ratio, leading to poor security. Compared to state-run prisons, private prisons have a 28% higher rate of inmate-to-inmate assault and twice as many inmate-to-officer assaults.

The private prison corporations spend heavily on lobbying for harsher criminal justice and immigration policies, contributing to mass incarceration. CoreCivic, the largest private prison contractor, spent $17.4 million on lobbying in the past ten years. In 2020 alone, private prison corporations spent a combined $4.2 million on lobbying the Trump administration.

Unfortunately, the executive order does not do nearly enough to tackle the private prison juggernaut. The order only affects 14,000 of the 152,000 federally incarcerated prisoners. This itself is a small fraction of the total prison population of 1.5 million for state and federal prisons combined. The contracts it impacts belong to only 12 federal facilities nationwide. The order will not lead to a decrease in the prison population, as the prisoners will simply be transferred to public facilities. It also does not actually terminate any contracts, but rather directs the Department of Justice to not renew existing contracts, which may run for years yet. And it is possible that if the Democrats lose the White House in 2024, the order will simply be revoked by the Republican president.

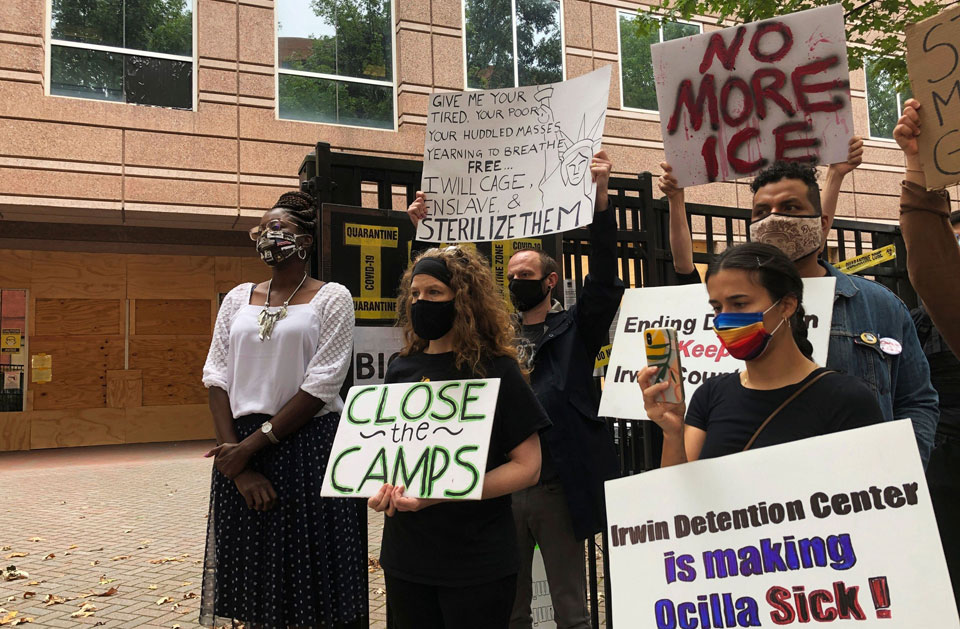

Federal immigrant detention facilities still privately run

The most glaring omission of the executive order, however, is immigration detention facilities. Biden promised during his presidential campaign that “the federal government should not use private facilities for any detention, including detention of undocumented immigrants.” But this executive order leaves out contracts under the Department of Homeland Security, and so the facilities under Immigrants and Customs Enforcement (ICE) remain untouched. Forty-six percent of ICE prisons are run by private contractors. Out of an average of 33,000 people detained in ICE prisons daily, 25,000 are held in private facilities. This is more than the entire federal prison population impacted by the executive order.

Immigration contracts swelled under Trump. Federal spending on immigration and enforcement increased by nearly 40% from 2014 to 2018, going from $5.3 billion to $7.4 billion. GEO and CoreCivic revenues increased by $121 million and $85 million, respectively. If the Biden administration wants to divest from private prisons, it must address ICE detention.

Aside from immigration detention, however, the private prison industry seems to be in a decline, and Biden’s executive order is sure to accelerate that decline. Private prison population peaked in 2012 with 136,000 people. Since then it has declined 12%. In total, 22 states do not house inmates in private, for-profit facilities, and there has been a recent move toward banning private prisons. California passed a bill in October 2019 to effectively ban for-profit prisons. The California bill will impact 1,400 people in three private prisons and 4,000 people in detention facilities. Banks like Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase, and Bank of America have also decided to divest from the private prison sector, citing the industry’s uncertain future because of the recent federal and state level bans.

But the industry is not going down without a fight. Private prison corporations expected a federal prison ban if the Democrats won the White House in 2020, and they spent heavily in political contributions ($2.6 million) to federal candidates, political parties, and outside groups. Ninety-two percent went to Republicans. But, in the case of a Democratic victory, they also had contingency plans in place.

Both GEO Group and CoreCivic have diversified their business models to include buying up re-entry facilities, or halfway houses, and transitioning to leasing out real estate. They have also founded a new advocacy group called Day1Alliance, which will not focus on lobbying or advocating for policies, but rather focus on shifting public opinion.

Even if the private prison industry collapses, our incarceration crisis will not be solved. Private prisons only account for 8% of the 1.5 million people currently incarcerated in state and federal prisons. Local governments continue to build jails, underwritten by the same private banks that are divesting from private prisons, in hopes of attracting federal prison or ICE contracts.

Of the $50 billion state governments spend on prisons, two-thirds goes to wages and benefits for those who work there. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, state and federal prisons employ 400,000 people and pay them decent salaries. The American Federation of Government Employees, the largest union representing prison guards, applauded Biden’s move away from private prisons because public prisons pay their employees more compared to private prisons, and they understand that the executive order does not place prison jobs under any real threat. We have to recognize the difficult fact that prison workers across the country rely on these jobs and see themselves as having a stake in preserving prisons. Local governments rely on jails and prisons for revenue.

Policies to reduce mass incarceration have to address both private and public prisons, and also reallocate the resources currently being poured into prisons in a way that addresses workers’ and communities’ need to replace incomes. To understand this, we can borrow from activists who want to defund the police, which is about reinvesting police department budgets on starved areas like health services, education, and community development.

If we truly want to reduce mass incarceration and reduce racial inequality, we have to tackle the problem of prisons as a whole – public and privately-run facilities. That will require the Biden Administration to pass more substantive policies, and will entail addressing the war on drugs, immigration, labor, and all the other issues connected to mass incarceration. However, the executive order is a positive step forward, as the abolition of the abhorrent private prison industry – which it certainly contributes to – is a worthwhile goal in itself.