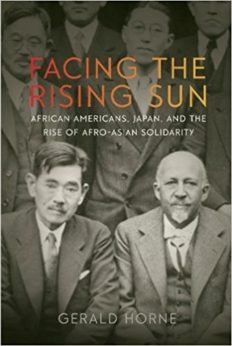

As a historian, Gerald Horne has spent decades investigating and uncovering the myriad alliances African Americans have built over the past two-and-a-half centuries—alliances designed to challenge slavery, Jim Crow, and racism, generally. Nearly forty books later, Horne, the Moores Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston, continues to add insight and nuance to this proud history of resistance.

Facing the Rising Sun: African Americans, Japan, and the Rise of Afro-Asian Solidarity, Horne’s most recent book, highlights a largely neglected aspect of the struggle for African-American equality—Afro-Asian solidarity.

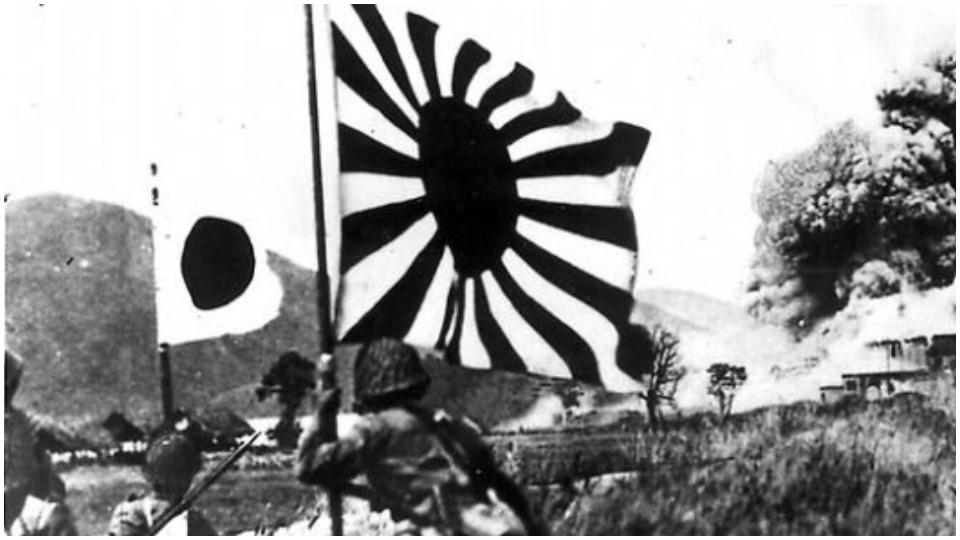

After the Civil War, as the United States feverishly expanded west, and further beyond the North American mainland, officials “encountered people not defined as ‘white,’ [and] inexorably they began to treat them in the despicable manner that mimicked how ‘nonwhites’ were treated at home.” However, “This policy boomeranged and served to drive Negroes, Japanese, and Filipinos closer together,” thereby laying the foundation for an Afro-Asian alliance wedged against white supremacy that would later emerge.

In the introduction, Horne notes, “W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, and other Negro leaders may have had conflicts among themselves, but all looked to Tokyo as evidence that modernity was not solely the province of those of European descent and that the very predicates of white supremacy were senseless.” Pro-Tokyo sentiment, Horne adds, “cut sharply across class lines: it was prevalent in the intellectual salons of Harlem, the plants of East St. Louis, and the fields of the Missouri boot-heel, stretching south into Arkansas and Mississippi.”

In many instances, African Americans sought arms, organized militias, met clandestinely with Japanese operatives, and traveled to the Land of the Rising Sun, where they were often treated like celebrities—a tactic of “gaining adherents who could prove useful in times of war,” which would come just a few years later. Indeed, many thought that a “race war” was imminent and saw the rise of Japan as a harbinger of white supremacy’s demise; they hoped to aid in its downfall through African-American pro-Japanese organizations like the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World, for example.

Horne notes that the “penetration of the U.S. Negro community by Tokyo” prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor added some legitimacy to right-wing Congressman Martin Dies’—as well as others’—assertion that “Japanese espionage” was “greater than the Germans ever dreamed of having…,” which ultimately lead to “a massive crackdown on Negroes expressing pro-Tokyo sentiment” during World War II. Though temporarily curtailed, the “crackdown” did not entirely squelch pro-Japanese or “Asiatic” sentiment within the Black community, a sentiment that would later re-emerge in the 1960s and ’70s through the Nation of Islam and within certain sectors of the Black Liberation movement, most notably the Black Panther Party, and their affinity for Maoism.

Horne—who has written extensively on the history of the Communist Party, USA—points out a historical irony in Facing the Rising Sun. He writes, “Indeed, the ideological tendency in Black America that was most immune to Japan’s charms—the Communist Party and those allied with this group—was precisely the tendency that received the most adamant and resolute opposition from U.S. rulers, which in a sense helped to further bolster pro-Tokyo stances,” and, he added, “even during the war [World War II], when Moscow and Washington were allied, certain authorities seemed more preoccupied with monitoring Communists than pro-Tokyo nationalists,” a sentiment 1960s and ’70s Black nationalists were keen to remember.

Ultimately, Horne argues, “Perhaps Communists were perceived as presenting a more systematic threat than pro-Japanese forces, who at worst threatened mere lives,” not the “all-important capitalist system,” a system then in decline, thereby providing spurious justification for the hounding and harassment of Black communists like Paul Robeson, Ferdinand Smith, and Benjamin Davis, Jr. Arguably, racism came into play here as well, as government officials, the FBI, and others, likely saw African Americans, their pro-Japanese organizations, and Japan itself, through race-tainted lenses, and were more prone to diminish and disregard their capacity for sustained organization, while exaggerating the capacity of those defined as Euro-American.

Regardless, African Americans were also more alarmed by the internment of Japanese Americans than their white counterparts—even those lead by the Communist Party. “Another reason why U.S. Negroes were inflamed to the point of attempting sedition was the mass internment of Japanese Americans…. This could be their fate too, thought many Negroes,” Horne concludes, a very real possibility given the context of the times.

Facing the Rising Sun is an important book. It adds significantly to our understanding of African-American resistance to white supremacy and should be read alongside Horne’s other works, specifically Race War!: White Supremacy and the Japanese Attack on the British Empire, as well as, The End of Empires: African Americans and India.

Facing the Rising Sun: African Americans, Japan, and the Rise of Afro-Asian Solidarity

By Gerald Horne

New York University Press, 2018, 240 pages

Comments