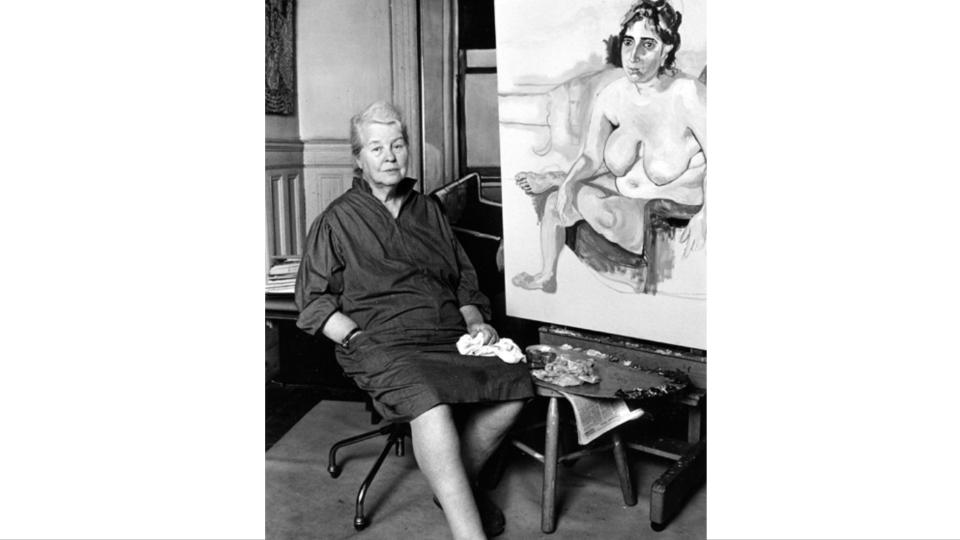

Virtually ignored for much of her early career, politically controversial, and at odds with conventional mores and art trends, Alice Neel’s life and work (1900-84) are beacons for socially conscious artists, particularly women.

After years of neglect, Neel’s art took hold in the public consciousness during her later period. Last year, she was celebrated by a glorious triumphant show at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Currently, her work is displayed at the immensely popular retrospective hosted by San Francisco’s De Young Museum. As art critic Roberta Smith wryly observed in the New York Times, “It’s time to put Alice Neel in her rightful place in the Pantheon.”

Neel was a figurative painter in the time of abstraction. As her predecessors and contemporary expressionists hied to abstraction, Neel’s use of line and color was put directly to the service of representation. While her more celebrated male abstract expressionist colleagues focused on color, shape, pattern, texture, and technique, Neel’s canvas work communicated with a wider audience through familiar images.

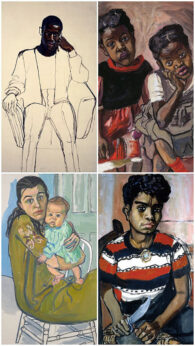

The political message of other expressionists may have been muted by their abstraction. Neel directly challenged both the traditional and emerging order. Not only was she a woman in a field dominated by men, she challenged the basis of this domination, the very old-school objectification of her gender. Her subjects and their depiction pushed political and social boundaries. She chronicled her times, clearly taking a stand by forging connection with ordinary people as well as celebrities, making recognizable emotions accessible. She fixed the relationship of her subjects to the social, personal, and class struggles of the century.

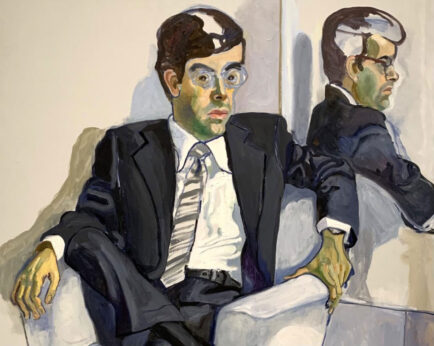

Friends, lovers, family, poets, other artists, strangers, political and cultural figures and events populate her canvases projecting the pain, grief, and joy of struggles and existence. The portrait of her son “Richard in the Era of Corporations” is an illustration of how “the corporations enslaved all these bright young men.” “Marxist Girl” (Irene Peslikis) is a good example of how Neel chronicled and promoted the new generation of feminist revolutionaries. “The Death of Mother Bloor” memorializes one of the first Red feminist members of the Communist Party who saw the link between the rights of women and the working class. “Nazis Murder Jews” dramatizes the 1936 New York May Day Parade, where over 40,000 Communists and Socialists drew attention to the Nazi atrocities already happening in Europe, years before the war.

Neel brought to her work the lessons of her tumultuous life, a commitment to engage in social change through her art. She came from a conservative, lower-middle-class, rural Pennsylvania upbringing. Classes at Philadelphia’s School of Design for Women were formative. There, she rejected the prevailing impressionism for the more gritty, rebellious Ashcan School, with its roots in urban realism.

Her own realism was dotted with hardship and tragedy. Neel’s first child Isabella died in infancy. Her husband Carlos abandoned her. Neel was hospitalized with a massive nervous breakdown and attempted suicide. After a year’s recovery, she became one of the first artists hired by the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project. A heroin-addicted lover set fire to her studio, burning over 350 of her watercolors, paintings, and drawings.

Undaunted, Neel began to garner notice, especially among progressive New York intellectuals. She illustrated the Communist Party’s Masses and Mainstream cultural magazine, showed at the New Playwrights Theater, and appeared with Allen Ginsberg in his film Pull My Daisy.

With the advent of the women’s liberation movement, Neel herself became a celebrity. She was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. President Jimmy Carter selected her for the National Women’s Caucus for Art Award for outstanding achievement. International shows and retrospectives followed, continuing after her passing. In 2007, Sundance Film Festival premiered the documentary feature Alice Neel, directed by her grandson.

Alice Neel ultimately succeeded not only through her artistry but because as her last two shows were titled, she put people first.

Comments