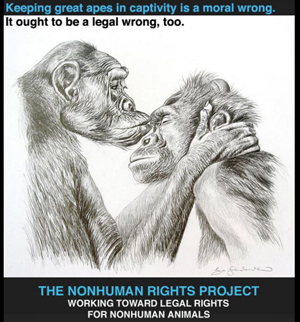

On April 20, a New York State judge did the right thing in a ruling in the case of two chimpanzees, Hercules and Leo, locked up in the scientific labs of Stony Brook University. The chimpanzees, (through their human legal representatives sponsored by the Nonhuman Rights Project), had petitioned the judge for a writ of habeas corpus so they could be released in an animal sanctuary.

Eventually, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Barbara Jaffe did not go so far as to grant “habeas corpus” but did clearly recognize the “personhood” of the two plaintiffs. This is rightly being seen as a major step in the advancement of the rights of nonhuman animals, which can lead to further progress.

We’ve come a long way, we animals. Animal personhood had, in past centuries been recognized only in the negative sense, that non humans could be punished as if they were human lawbreakers, but not treated as persons otherwise. In the Middle Ages in Europe, on several occasions pigs and other animals are said to have been tried and executed for murder. On one occasion, a sow was executed for eating a human baby but her little piglets, though brought up on charges, were found innocent because they were “too young” to be held criminally responsible for their actions.

There are stories about dogs being hanged for witchcraft, including cases from the famous Salem witch trials in colonial Massachusetts, though there are disputes about whether the dogs were seen as practicing witchcraft or merely possessed (scholars of German literature will recall that in “Faust” by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Mephistopheles, an avatar of Satan, infiltrates Dr. Faust’s office at Heidelberg University in the form of a cute little “Pudel”).

But if non-human animals could commit crimes, does that not mean they are persons? And if they are in any sense persons, do not we human persons have some sort of ethical responsibility toward them?

One of the most important figures in European philosophy, the 17th Century French mathematician and philosopher, Rene Descartes, thought not. Descartes declared that nonhuman animals were an order of creation different from human beings, because God did not give them souls. The evidence for this was the limited flexibility of their behavior, and especially the fact that only human beings can speak. Descartes conflated the ability to speak with the ability to reason, a dubious proposition which seemed convincing to him and to people influenced by him. Descartes thought that animals were only machines because of this fundamental lack, which was due to God’s favoring of human beings over animal creation. So we can eat them without an apology.

As science has advanced and religious dogma retreated, the absolute distinction Descartes drew between rational humans with souls and speech and animal machines without has steadily broken down. Scientists have realized that even though other animals do not have the capacity for language and speech that we have, many species have very sophisticated communications mechanisms that allow them to make rational judgments to ensure their survival. Moreover, a surprisingly large variety of species also show a propensity for mutually supportive social behavior, few more than chimpanzees and other apes and monkeys.

The studies with chimpanzees and the closely related bonobos by Jane Goodall and Franz de Waal, among others, have opened up an entire new field of the study of animal sociality. A key work in this endeavor is Franz de Waal’s 1996 book “Good Natured: The Origins of Right and Wrong in Humans and Other Animals” (Harvard University Press). De Waal promotes the thesis that there is continuity between empathetic behavior among different primate species, including humans, and that this is in spite of the language-no language distinction. Since its publication, many other studies have produced similar results.

If Descartes’ distinction between the fundamental nature of humans and non-human animals is utterly refuted and long abandoned, then do not humans have an ethical obligation to non human animals, as we do to each other? And is there more to that than “don’t beat your donkey” legislation and Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty legislation that exist all over the world? Should non-human animals be recognized as having legal, civil rights? And if so, what should these be?

Many have noted the hypocrisy of bourgeois humanitarians who care more for non-human animals than they do for their fellow humans. However, I don’t think that this is an inevitable state of affairs. If we handle this right, advances in the topic of the rights of animals can be part of a strategy for finally getting recognition for human rights – for humans!

Photo: Nonhuman Rights Twitter.

Comments