We’ve had a little time to reflect on the massive Feb. 3 Norfolk Southern rail wreck in the small Ohio town of East Palestine, and there’s one good thing to be said about it: Nobody died.

Yet.

We introduce that warning for several reasons.

We are approaching the tenth anniversary of the Lac Megantic rail disaster in a similarly small town in southern Quebec, where an oil train’s brakes failed, it rolled downhill, gathering speed, jumped the tracks, crashed, and its cars blew up. The resulting July 6, 2013, fire and blast spread 1-1/2 miles, destroyed the small town’s downtown, and killed 47 people.

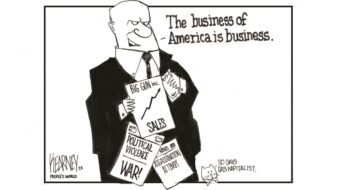

Lac Megantic, like East Palestine, was completely preventable. The reasons both occurred can be traced to corporate greed.

In Lac Megantic, the railroad had convinced Canadian officials the train needed just one crew member, the engineer. He was on a break when the brakes failed. Had there been a conductor to keep an eye on the train and especially the brakes, it could have been prevented.

The East Palestine train had an engineer, a conductor, and a trainee. They detached the engines from the rest of the train, preventing an even worse disaster than occurred. But corporate greed intruded there in the sensor system Norfolk Southern used to check if brakes were overheating. NS and other railroads have been campaigning for more sensors and fewer people to check brakes.

The trackside sensors, miles away from each other, relayed signals to a control center far from East Palestine. Only when the temperature on the brakes exceeded 200 degrees Fahrenheit above the surrounding air—East Palestine was at 10 degrees above zero on Feb. 3—would an alarm sound in the engine cab.

By the time the train passed sensor #3, the brakes were 253 degrees hotter than the air. The alarm sounded, too late. The heat broke the axles, the train derailed, and disaster ensued.

The railroad that ran the Lac Megantic train didn’t tell provincial or town officials that an oil train was coming through and that they should take appropriate precautions. Norfolk Southern didn’t tell state, county, or local officials its 150-car train had cars with hazardous chemicals aboard. Rail lobbying got the Republican Trump regime to weaken rules governing “hazardous trains” and such warnings.

No person has died yet from the East Palestine blast, though at least 3,500 fish in the river that runs through the town have died from the chemicals dumped into it and so have people’s pets.

But lethal combinations of toxins, such as those the East Palestine crash produced, often kill people years after the blast itself occurred. Just ask New York City’s unionized Fire Fighters.

Every year, another few die from rare cancers or other unusual illnesses caused by the combination of toxins, asbestos, particulates, jet fuel, and who knows what else, released by the Sept. 11, 2001, al-Qaeda airliner attack which destroyed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

Some 343 New York Fire Fighters and their priest—all union members—died that day. So did other unionists working in the WTC. Later, so did unionists who toiled for months afterwards on “The Pile,” cleaning up the mess while seeking remains of victims who perished.

It is almost 22 years later, and the Fire Fighters are still sick and dying.

Back in Ohio, 39 unionized Maintenance of Way Employees members, sent to clean up and fix the tracks where NS32 wrecked, are reporting nausea and migraine headaches. How about East Palestine’s residents? How will they suffer and die in the coming years from the chemicals and poisons the crash released?

Finally, and this is the biggest hazard of them all: The East Palestine wreck and the Lac Megantic catastrophe both occurred on a single railroad track in a lightly populated area, involving two small towns. Yet there is always the possibility of a crash and explosion in a larger area with many more rail lines, and many more trains running through them every day—trains which may be unsafe, thanks to corporate greed.

Sen. Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill., didn’t push that point, at the Senate hearing on the East Palestine wreck. She didn’t have to. She just pointed out that Chicago, the nation’s rail hub, hosts 1,300 freight trains every day, in a city of 2.6 million, on 3,685 miles of track.

One oil train blast there, on a freight heading towards or away from the oil tanks on the South Side or near the canal that parallels the Stevenson Expressway or in nearby Northwest Indiana, and you would have a catastrophe that would dwarf what we’ve seen in East Palestine, or Lac Megantic.

Similar hazard “choke points” exist nationwide where an oil freight train blast would cause immense damage. The freight tunnel leading up to Baltimore’s Penn Station. The elderly Hudson River freight and passenger tunnels leading into New York City. The West Coast freight line where a derailment closed Interstate 5 in Oregon for hours. And so on.

Which is why the wreck in East Palestine, and the corporate greed behind it, is such a warning. All because of that one simple word: “Yet.”

As with all op-eds published by People’s World, this article reflects the opinions of its author.

Comments