Ella Reeve Bloor (1862-1951), or “Mother Bloor” as she is known to history, is famous in labor circles for her work as an investigator of child labor, as a socialist organizer, and as a founding member of the Communist Party. She even worked with Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle, to help gather data to expose the meatpacking industry. Perhaps unknown to many though, she was also a key figure in the farmers’ struggle in Iowa during the Great Depression.

In the 1930s, the country was consumed by economic famine. The Corn-Belt state of Iowa, part of “the breadbasket of the world,” was no exception. Across the state, many homes and farms were foreclosed by the banks, leaving farmers and their families broke, hungry, and angered by their daily conditions.

In his review of Lowell Dyson’s authoritative history of Communist organizing in the countryside, Red Harvest: The Communist Party and American Farmers, Maurice Isserman wrote that beginning in the 1920s, “the Communists made determined, if sporadic, efforts to extend their influence past city limits.”

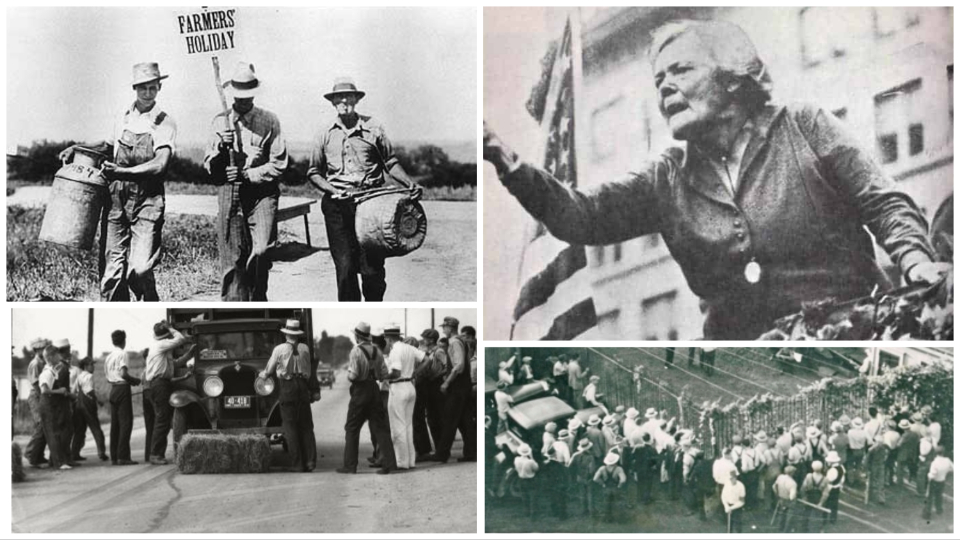

Bloor, who earned the nickname “Mother” in the 1930s, was a part of these efforts. She served on the Central Committee of the CPUSA from 1932-48, years when the party was at the height of its influence. She and her son, Harold Ware, and fellow CPUSA member Lem Harris set out to organize farmers and workers in the Hawkeye State, forming an alliance with a group known as the Farmer’s Holiday Association (FHA).

As recounted by Iowa historian George Mills in his book A Judge and a Rope, and Other Stories of Bygone Iowa, the FHA “was at the heart of the protest movement and was out in front in clashes around the farm belt.”

Bloor set up an office in Sioux City, as well as a temporary outfit in Le Mars, with the hope of uniting the unemployed of the cities with destitute farmers in the countryside. She organized countless meetings with workers, farmers, and others sympathetic to their plight.

She played a major role in the Milk Strike of 1932, also known as “The Great Milk Wars of Sioux City.” Farmers protested the low wages they were paid by stopping cars from delivering milk to markets to demonstrate how valuable their labor was to the rest of the community. If the trucks or cars did not turn around, the dairy deliveries were dumped by picketers.

That year, Iowa Farmers’ Union president Milo Reno, a co-founder of the FHA, issued an “ultimatum” to the “other groups of society,” to borrow Reno’s phrase:

“If you continue to confiscate our property and demand we feed your stomachs and clothe your bodies, we will refuse to function. We don’t ask people to make implements, cloth, or houses at the price of degradation, bankruptcy, dissolution, and despair.”

In response to the situation facing the farmers, Bloor and the FHA organized highway picketing in Sioux City, Iowa, to stop food from being delivered to the market for thirty days or “until the cost of production had been obtained,” as Reno said in his ultimatum.

While some disagreed with the tactic of dumping milk as a sign of protest, viewing it as wasteful, many people agreed that the protesters’ frustration was warranted.

State officials at the time blamed “Communist subversives” for the “instances of violence in northwest Iowa.” This view was shared by Governor Clyde L. Herring, state Attorney General Edward L. O’Connor, and Major General Park Findley of the National Guard, who referred to Sioux City as “a hotbed of Communistic activity.”

One time, the Iowa National Guard raided Mother Bloor’s Sioux City office, seizing literature and whatever else they saw fit to confiscate. According to George Mills, “One circular urged a farm march on the Statehouse in Des Moines and also accused President Roosevelt and Governor Herring of being tools of the big bankers.”

The struggle of America’s farmworkers was one that she continued to dedicate her attention to in the 1930s – not only Iowa, but also Montana, Nebraska, and the Dakotas.

As a home-grown revolutionary throughout her life, Bloor was variously a member of the Social Democracy of America, the Socialist Labor Party, the Socialist Party USA, and finally the CPUSA. After Iowa, just as before, the rest of Mother Bloor’s years were dedicated to workers’ struggles and other progressive causes.

In 1937, Life magazine called her “the grand old woman of the U.S. Communist Party.”

CPUSA member Elizabeth Gurley Flynn characterized the late organizer and revolutionary in the following manner:

“We love and honor this extraordinary American woman as a symbol of the militant American farmer and working class, of the forward sweep of women in the class struggle and in our Party, as an example to young and old of what an American Bolshevik should be.”

Comments