WASHINGTON—1968…the year all hell broke loose worldwide, or so it seemed then.

Students hit the streets from Tokyo to Cairo to Chicago. Opposition to the U.S. war in Indochina was the main theme, but there were secondary and local causes, too—from protesting a sick economy and a discredited president in Egypt to campaigning against an aloof ruler in France. Soviet tanks overthrew the reformist Czechoslovak Communist government of Alexander Dubcek’s “Prague Spring.”

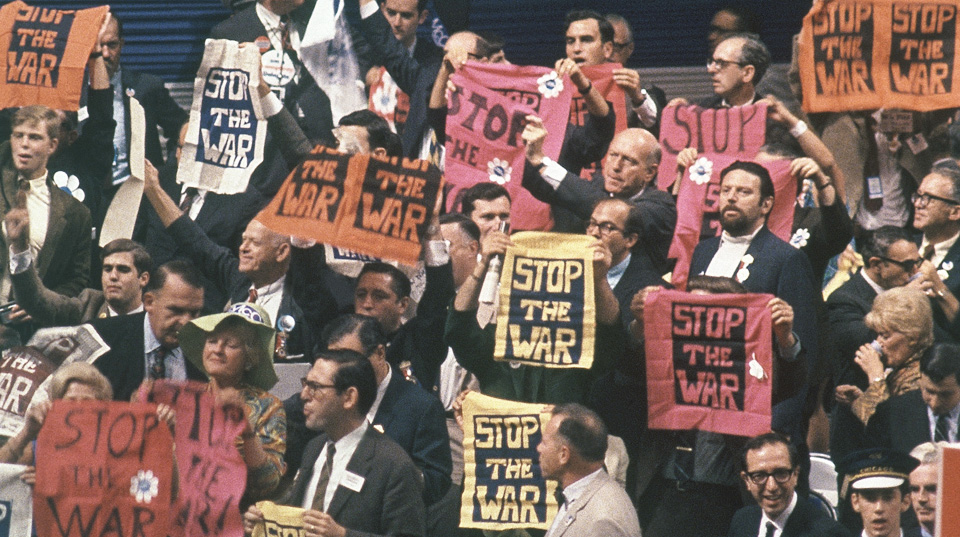

The U.S. lurched between a detested president, the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, riots in cities after King’s murder, the black power movement, and the “police riot”—as an impartial report put it—surrounding the late-summer Democratic National Convention in Chicago. That conclave itself was a maelstrom inside the International Amphitheater on the South Side.

And on top of that came the Kerner Commission report about the U.S. becoming two societies, one white, one black, separate and unequal, the Poor People’s Campaign King organized before his murder, the youth “counter-culture” of peace and love—and pot and speed—and the right-wing backlash against all of that which racist George Wallace rode to prominence and Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon exploited as the so-called “Southern Strategy” to win the White House.

And that’s just for starters.

Fifty years later, 2018, is enough time for historians to step back and look at all those events and put them in perspective. Panels of them did so at the American Historical Association convention Jan. 4-7 in Washington, D.C. What they found were lasting impacts, here and abroad.

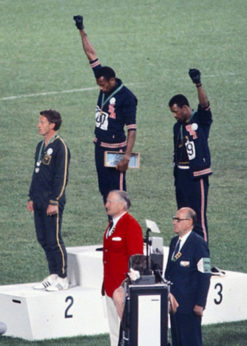

Some of the panels and papers were esoteric. The panel on black power focused, for example, on movements in sub-Saharan Africa, without a mention of the black power movement in the U.S., symbolized by raised-fist salutes from U.S. track winners Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, or the role of the Black Panthers. But the main forum on 1968—the introductory one—made up for that.

“The student movement and protest was the start of something larger than just leftist politics,” said City University of New York professor Stephanie Boyle. Though she was speaking of Egypt specifically—post-protest repression of students and workers there led to the rapid rise in influence of Islamism in the Middle East’s most-influential nation—other panelists said that statement could apply worldwide.

“Radicalized artists” became “a global phenomenon” and helped spread the protests, added Andrew Ivaska of Concordia University. “There was a dense mix of politics, history, sex, and mystery.”

That the war’s carnage and brutality were televised worldwide triggered most of the protests, he pointed out. It sent millions of students, leftists, and activists into the streets, in 1968 and afterwards. It was “the major realization that politicization could be both multi-local and global,” said Ivaska. In one example he cited, there were 67 campus takeovers, with opposition to the war as the cause, in Japan alone in 1968.

That phenomenon of mass protests on multi-local and global causes continues today, the panelists said. And so does a little-noticed facet of 1968, said UCLA’s William Marotti: The change in the status of China from its former position as “a geographic location” to “being a site for ideas.”

The Chinese, then still going through the Cultural Revolution, “became subjects of activism” in 1968, he elaborated. “Maoism presented itself” to protesters, students, and activists “as an alternative to both capitalism and to the Soviets’ structure, just as the crisis came most to light.” Another panelist pointed out the Black Panthers used Chairman Mao’s “Little Red Book” as a guiding text.

But if 1968 was a fount of protests, the panelists said, the activists failed on another level. The historians pointed out that unless the masses in the streets have a definite aim, such as ending the war, they don’t win. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction starts and sets in—and after 1968, lasts.

The historians’ panel on 1968 counter-reaction covered Mexico, Japan, Argentina, and West Germany, discussing events such as Mexican troops shooting down students at the Autonomous National University outside Mexico City. But on the introductory panel, American University historian Ibram Kendi tackled the U.S.

“How do we as historians negotiate 1968 at this time and place?” asked Kendi, a noted author and just-named head of a new African-American institute at the D.C. university. “The best way for us here is to” investigate the ethos “of the prevailing American mind, which is the white American mind, which is the racist white American mind.”

That showed up even as early as LBJ’s State of the Union Address to Congress that January, before 1968 really broke loose. In 1966-67, the country saw rising anti-war protests against the war, fatal riots in Detroit and elsewhere, and the growing youth counter-culture. All that and more, Kendi said, disturbed the white majority, and the politicians who represented it.

So when Johnson called for a fair housing act, or cited the Kerner Commission report about two societies, he got tepid applause. But when Johnson criticized the rioters, he brought the house down.

“Many of the politicians” and the white constituents they represented “were raging against the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and against cultural change,” Kendi said. Pols were particularly incensed by African-American activism because they and their constituents inherited centuries-old attitudes of “blacks as inferior humans.”

The continuing anti-black attitude by whites and politicians is another legacy of 1968, Kendi stated. “To them, Black Power meant black supremacy and not white supremacy, just as in 2018, the Black Lives Matter movement means black supremacy and white opinions don’t count.”

“So ‘Law and order’”—the slogan of Nixon and Wallace—“was used to justify brutality, and those fears came to dominate political campaigns over the next five decades,” Kendi explained.

Nixon’s successor “conceptualized this by saying ‘Make America Great Again,’” the professor said, without naming current GOP President Donald Trump. “In many ways, we are living with the consequences” of that Nixonian decision, he commented.

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom. In answer to an audience question, Kendi called MAGA “a global phenomenon,” while at the same time saying “the resurgence of nationalism in the U.S. is overblown.” He did not elaborate on that statement. Nationalism, however, seemed to be different in Kendi’s remarks from nativism and racism.

“If you believe racism ended with LBJ signing the Civil Rights Act” of 1964 “and the Voting Rights Act” of 1965, “then you see this”—1968—“as an explosion.”

“But if you see it the other way, then you see” both positive “progress, and racist progress, too, since then,” simultaneously, Kendi elaborated. Other panelists differed, though,

“There has been a turn to the right,” not just in the U.S., but in Europe—east and west—since 1968, Marotti said. “It’s still going on in the Middle East, too,” said Boyle, a scholar of Arab nations’ history.

Comments