AKRON, Ohio — Joe Hill was a labor organizer and songwriter for the Industrial Workers of the World, founded in 1905. He believed in the IWW mantra that men and women of all races and nations could work together to “change the unequal conditions of society through legitimate direct action.” His tool for uniting people was music and the power of song. He was one of the most influential protest artists of the 20th century, and if Joe Hill were around today, he’d still find plenty to protest.

Folksinger Tom Kastle’s performance of the musical play, Joe Hill, Alive as You and Me, celebrates the legacy of the martyred poet and labor leader. The tone is set by the script’s opening lines:

On November 19, 1915, a man named Joe Hill was shot by firing squad in Salt Lake City, Utah—his crime? Writing songs!

What follows, described by the show’s creator as “an evening of songs, stories, and solidarity,” is a remarkable 70-minute collective experience.

Joe Hill was born Joel Hägglund in Gävle, Sweden, in 1879. His father Olaf worked as a conductor on the coastal railroad. In his spare time, he built a homemade organ so his children could learn music. Olaf’s death in 1887 left the family destitute, and in 1902 Joel and a brother emigrated to the United States.

In New York the Swedish greenhorn worked menial jobs, making extra money playing piano in saloons. He went by the name Joe Hillstrom at first, then settled on the fully Americanized “Joe Hill” and moved to Chicago, where he worked in a machine shop until he was fired for trying to organize a union.

Joe joined the IWW around 1910. He quickly realized that the way to bring workers together was not to hand out political pamphlets but to get them singing. To that end, he took already known tunes and composed new lyrics designed to teach about the class war and instill courage.

Hill contributed these pieces to the IWW’s widely circulated Little Red Song Book. Among Joe’s best works are “Casey Jones–A Union Scab” and the anthem “Rebel Girl,” inspired by the charismatic strike leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Hill’s masterpiece is “The Preacher and the Slave,” which attacks the “holy rollers” who tell the poor to accept their misery because they’ll get “pie in the sky” when they die.

On January 10, 1914, Hill knocked on the door of a Salt Lake City doctor at 11:30 p.m., seeking treatment for a bullet wound and stating that he’d been shot by an angry husband who accused him of insulting his wife. Earlier that same evening, in another part of town, a grocer and his son had been shot and killed. Hill’s injury subsequently linked him to the incident. All the evidence was circumstantial, but the uncertain testimony of two eyewitnesses and the lack of any corroboration of Hill’s alibi were enough to convince a local jury of Hill’s guilt.

An appeal to the Utah Supreme Court failed, as did requests for clemency from President Woodrow Wilson, the Swedish ambassador, Helen Keller, and thousands of U.S. and Swedish citizens. The international campaign to free Hill grew steadily stronger throughout 1915, but it couldn’t match the power of the Utah Copper Company, which wanted Joe dead.

Hill’s prison letters and continued agitation while awaiting execution created a legacy that made him more famous in death than in life. To the great IWW leader Bill Haywood, Hill wrote, “Goodbye Bill: I die like a true rebel. Don’t waste any time mourning, organize!” In a letter to the editor of the Salt Lake Telegram, Joe ended with these words: “I have lived like an artist and I shall die like an artist.” At the moment of his execution on November 19, there was a pause, and Joe, impatient with the pace of the proceedings, yelled “Fire already!”

Thirty thousand mourners attended Hill’s funeral in Chicago. His body was cremated, and six hundred small envelopes containing his ashes were sent around the world to be scattered to the winds on May Day 1916.

In 1936 Earl Robinson set Hill’s story to music in “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night,” a powerful ballad with lyrics by Alfred Hayes that has since been covered by the likes of Paul Robeson, Woody Guthrie, and Pete Seeger. At a little festival called Woodstock in 1969, Joan Baez sang beautifully about Joe Hill. Bruce Springsteen rocked a full-orchestra tribute to Joe Hill for International Workers Day in 2014.

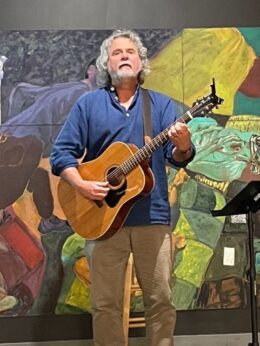

Millennials and Gen Z’ers typically know very little about “the man who never died,” but Tom Kastle would like to change that. On the afternoon before his November 2 performance in Akron, Kastle visited our undergraduate American Studies class at the University of Akron to talk and answer questions.

Asked about his background, Kastle explained that he’s a busy activist who grew up in a Chicago union household. For years he has participated in solidarity sing-alongs in his current hometown of Madison, Wis. He has marched and demonstrated in many protest actions, sometimes lifting morale with his guitar and voice, but he acknowledged with some regret that in his youth he was never taught much about the deep history of the labor movement.

A year ago, he was approached by David Simmons, founder of the Madison-based Fermat’s Last Theatre Co., which creates and promotes plays about social justice issues under the slogan “serious theater, radical truths, always free.” Simmons’s Joe Hill script immediately interested Kastle, who saw it as a chance to learn and teach not only about Hill but about the radical labor culture of the IWW. “These guys were into surrealism and poetry and music, and I was like, wait a minute, unions and surrealists? It’s a really fascinating thing.”

It makes sense that Kastle, a folksinger and agitator, would commit his energies to a play in honor of Hill, who helped define the genre of protest music and people’s songs. And Tom doesn’t sing solely for reasons of money or fame. He’s satisfied if his talents help to educate about progressive ideas and present-day labor issues. Tom is not a nine-to-fiver because “It’s about having more time to enjoy and do the things you want to do in life,” he told the Akron students.

That evening, Tom gave a performance funded by a grant from the University of Akron and held at the Summit Art Space, a community-supported venue in the city’s Historic Arts District. Councilwoman Nancy Holland, a labor lawyer who has also served on the Akron Civil Rights Commission, attended as an honored guest and participated in a post-performance Q and A.

Joe Hill, Alive as You and Me is a one-man show, two if you count Kastle’s guitar. They took the small but rapt audience through a sometimes laughing journey, with some class war horrors en route.

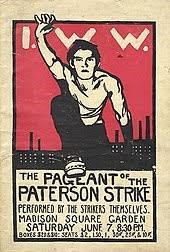

Kastle described the poetry, politics, and visual culture of the IWW, along with the organization’s notorious strike actions in the textile mills of Lawrence, Mass., in 1912, and a year later among the silk workers of Paterson, N.J. We learned about the Paterson Strike Pageant, a moving reenactment of events of the strike before an audience of 20,000 at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. Among other topics typically absent from textbooks but covered by Kastle were the heroic activism of labor icons Lucy Parsons and Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, set against industrialist atrocities like Henry Frick’s brutal Homestead Massacre of 1892 and John D. Rockefeller’s horrific Ludlow Massacre of 1914.

Kastle described the poetry, politics, and visual culture of the IWW, along with the organization’s notorious strike actions in the textile mills of Lawrence, Mass., in 1912, and a year later among the silk workers of Paterson, N.J. We learned about the Paterson Strike Pageant, a moving reenactment of events of the strike before an audience of 20,000 at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. Among other topics typically absent from textbooks but covered by Kastle were the heroic activism of labor icons Lucy Parsons and Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, set against industrialist atrocities like Henry Frick’s brutal Homestead Massacre of 1892 and John D. Rockefeller’s horrific Ludlow Massacre of 1914.

Literally surrounded by the “local color” of Akron-area artists, in a people’s place open to all, we felt solidarity not only with the show’s historical content but with the beautiful songs written at a time when the ruling class did not want to hear them, but many wanted to sing them. Kastle’s passions for his art and for the aspirations of workers were apparent. It’s fitting that Joe Hill was brought to life in these surroundings and that the evening ended with Kastle and his audience singing,

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night

Alive as you and me.

Says I, “But Joe, you’re ten years dead.”

“I never died,” says he.

In the post-show discussion, Councilwoman Holland drew hopeful analogies from Simmons’s script and Kastle’s performance, connecting both to today’s newly energized labor activism.

Then someone mentioned Ralph Chaplin, the IWW bard and author of “November,” a song written in the 1930s that eulogized Hill alongside Chicago’s Haymarket anarchists, who were executed in the eleventh month of 1887. Chaplin’s lyrics encouraged remembrance of the “hallowed month of Labor’s martyrs.”

Now is a good time to talk and learn about Joe Hill, as we did on a November evening in Akron.

Joe Hill, Alive as You and Me, presented by Fermat’s Last Theater Company of Madison, Wis., and scripted by David Simmons, featuring singer/storyteller Tom Kastle, is available for bookings nationwide.

Comments