Mike Evans worked as the lead organizer for the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM) at the Boeing plant in North Charleston, SC. On Wednesday, February 15 he spoke of his disappointment that workers had voted against joining the union. “We are disheartened they [Boeing employees] will have to continue to work under a system that suppresses wages, fosters inconsistency, and awards only a chosen few.” To him, this was about more than just a setback for the broader labor movement.

Deeply disconcerting for supporters of the workers has been the way in which Boeing has threatened their livelihoods already. On February 14, the New York Times reported that the second largest aerospace and defense contractor has been considering firings—in corporate-speak, “involuntary layoffs”—in South Carolina because of worries about their major competitor, Airbus.

But such actions seem financially unnecessary. According to Fortune, Boeing’s profits in the third quarter of 2016 alone were up more than 30 percent and 2.28 billion dollars.

Boeing executives, eager to crush an effort at a plant they considered union-proof, spent millions to strand their employees without collective bargaining. Not only did they purchase digital billboards urging a “no” vote, they paid for expensive television airtime that manipulated fear and anxiety to get the outcome they wanted. Commercials, one showing the organizing effort at a casino run by “labor bosses,” made a lurid effort to manipulate the worker’s understandable fears.

Workers, speaking on condition of anonymity, have said that many of their direct supervisors spoke against the union at the plant itself, which is a violation of labor law. Moreover, the company apparently ran some of the same commercials they spent millions on for local TV in break rooms inside the plant, as well as videos that alleged that workers in other parts of the country “worried about their children” after their plant had become unionized.

As I recently reported for People’s World, the company made it difficult for IAM and community allies to picket in solidarity with the workers, including inexplicably being allowed to use Charleston International Airport security to force us to leave.

The decision of Boeing employees to register a “no” vote probably seems easily explicable. The American South, and South Carolina, has a long anti-union tradition dating back at least to the 1950s and the emergence of “right to work” laws through much of the South that took the teeth out of collective bargaining. Today, South Carolina has the lowest rate of unionization of all the states in the nation.

Cultural explanations don’t go far enough, while they also make it easy for allies of labor to write off the state and the South as a whole. Despite so-called “right to work” policies and a hatred toward unions that seems bred out of the southern soil, there’s both an alternative history of the region and a set of explanations that have little to do with traditional images of the South.

Southern labor struggles

Charleston itself is home to a very strong International Longshoremen’s Association, Local 1422. A largely African-American union, the ILA has been struggling with a deeply racist and entrenched economic hierarchy since its inception. Their membership includes some of the most inspiring examples of the struggle for labor in American history. In 2001, police arrested five members of the ILA—who came to be known as the Charleston 5 — for picketing a non-union Danish freighter using the port. The state threatened them with the charge all protesters fear; felony riot that carries a ten year sentence. Worldwide protest and the obvious political motivation of the prosecution led to their release with all charges dropped.

The ILA membership stood with IAMAW and Boeing employees throughout this latest struggle. They also have shown solidarity by working alongside Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) health workers who are seeking better wages and clarity regarding grievance processes.

A labor tradition even older exists in the Carolinas. Most labor historians believe that the largest strike in American history in a single industry may have been what’s called “The Uprising of ’34.” Workers in the textile industry walked off spinning room floors up and down the spine of the Appalachians.

Red flags waved in western North Carolina cities. The strike spread into north Georgia and Alabama. In Honea Path, South Carolina, hired guns shot and killed seven striking workers and wounded 30 others. While giving in to some demands, mill owners blacklisted strike leaders at all levels. The National Guard, at the direction of Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge, placed strikers in internment camps, previously used for German prisoners in World War I.

Finally, organized labor throughout the Southeast, and through much of the South, has taken on a much more grassroots identity than many in other regions of the country are accustomed. Charleston, in part because it’s a tourist destination, has thousands of low wage fast food workers. In recent years, they too have recognized that their interests are fundamentally opposed to management.

The Fight for 15 movement has attracted these workers who, in recent weeks, launched a campaign against Secretary of Labor nominee Andy Puzder on the sidewalks, parking lots, and sometimes inside of local Hardees, one of Puzder’s fast food chains.

Fight for 15 led the movement against Andrew Puzder throughout the nation, staging a major demonstration at his corporate headquarters in St. Louis. On February 15th, Fight for 15 sat in at the North Charleston office of Senator Tim Scott, one of four Republican Senators whose lack of support for Puzder helped force the nominee’s resignation the same day.

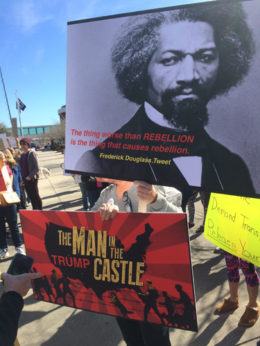

Trump visited Charleston after the Boeing vote, supposedly for the unveiling of Boeing’s new “Dreamliner 787” but also likely to crow with executives over their success in preventing workers from organizing. He was greeted with hundreds of protesters who, though not able to get on Boeing grounds, gathered as close as they could, booing Air Force One as it made its quick flyover.

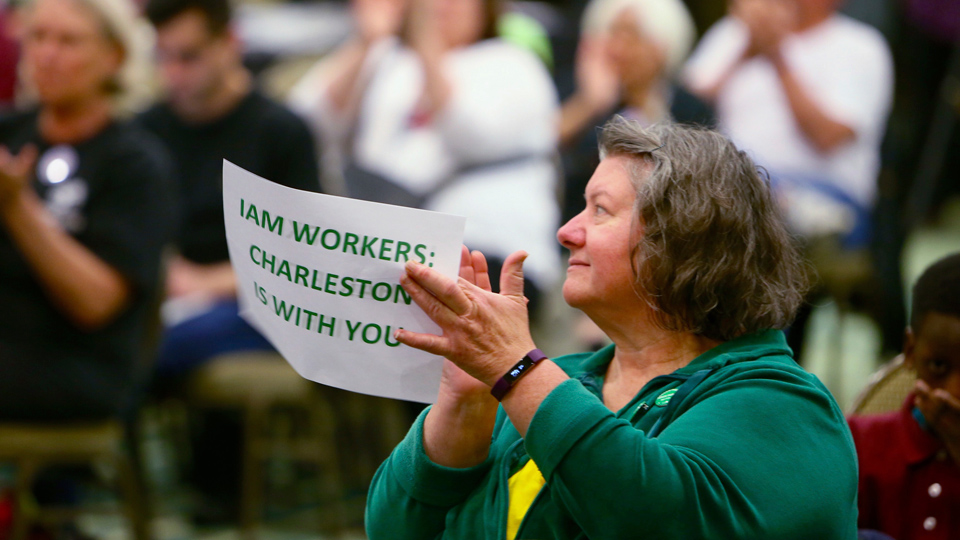

Organized by Indivisible Charleston, a national grassroots umbrella organization that has been using the internet to connect people to days of actions and protests, the rally participants expressed mainly economic concerns. One protester, holding his RESIST sign high, described himself as a retired worker who had saved all his life to “try to stay in the middle class.” Elaine Cooper, who works with the Democratic Labor and Progressive Caucus, expressed disappointment at the vote. “Sometimes people do vote against their own interests,” she told me. But, she pointed out, how could workers resist the onslaught of fear that Boeing had unleashed?

Here in conservative South Carolina, liberals have started asking more and more questions about the economic roots of the Trump administration’s malevolence. They look at his cabinet of crony capitalists and it raises questions about the system more generally: has it all been a criminal enterprise from the start with its worst aspects now on full display?

Comments