NOTICE: Some sections of the original version of this article have been retracted because they included unverified and/or unverifiable claims concerning a member of the faculty at Wayne State University.

ANN ARBOR, Mich.—As another Midwest winter finally began to give up the ghost and another term was coming to an end for students on campus, graduate students at the University of Michigan decided to take uncertainty into their own hands.

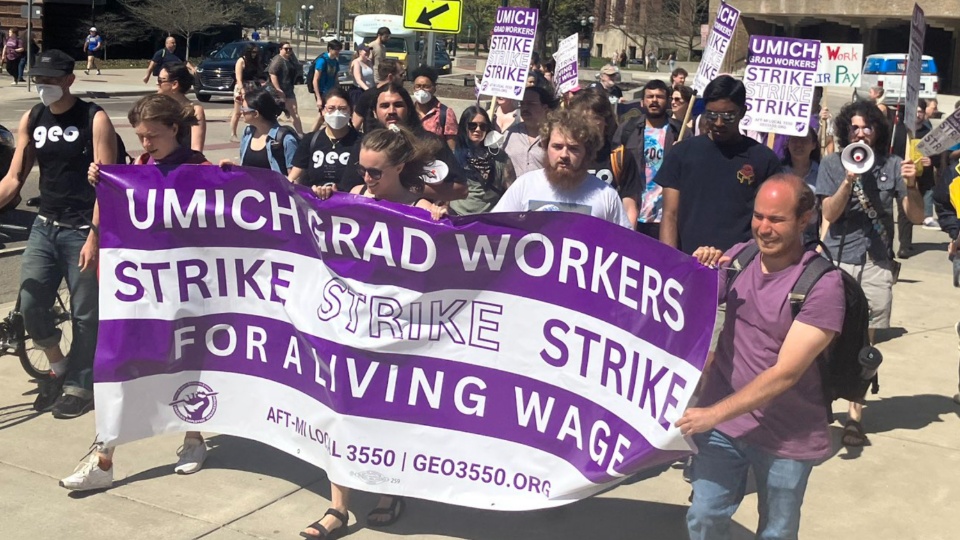

With only a few weeks left in the term, the Graduate Employees Organization, or GEO, at the University of Michigan went on strike on March 29. What brought them to strike was the need for a living wage: The current average salary of a graduate student is $24,000 a year, and the union is looking to get this to $38,000.

Although striking is illegal according to both state law and GEO’s contract—GEO even admits such—the grad students decided to gamble on whether the university would prefer to clean house or pay them a living wage anyway.

April was a contentious month for the striking workers. Their pay ceased on April 2. The university sent out an email warning the strikers they would not be paid for any time not worked. The email also said all graduate student instructors and staff assistants (GSIs and GSSAs, respectively) were required to complete attestation surveys beginning the week of April 9. The union advised its members to not fill out or sign them.

The university then sought a Washtenaw County Circuit Court order to force them back to work; the court refused to intervene.

Not a week later, a different Michigan-based judge ruled the strike was an unfair labor practice. The students’ contract, which ended May 1, contained a no-strike provision, which administrative law judge David Peltz ruled a breach of the graduate student union’s duty to bargain in good faith.

On April 20, on the day that students should have received their normal paycheck, U of M President Santa Ono sent campus police to forcefully remove workers picketing around his SUV while he was out to dinner.

Now that commencement season is over and the campus has quieted down, the striking workers’ future is still on the table.

Beyond pay

Although the demands for a living wage have been at the forefront of their strike, the graduate students’ platform goes beyond pay. It proposes radical changes in campus security, minimum standards for COVID and disability safety, and basic healthcare.

It also addresses issues specific to particular groups of students. International graduate students, for instance, are hit with extra expenses from taxes and visa submissions which are not covered by the university, and Master’s students are often not included in the discussion of open teaching positions. The union wants both of these things to change.

It also looks beyond the troubles of the higher education industry: Transgender healthcare, reproductive rights, workload, and harassment and discrimination are also addressed.

Considering widespread state and personal violence against the trans community, the ubiquity of abortion bans, the mental health(care) crisis, and the persistence of workplace power imbalances, the GEO’s bargaining platform reads less like a union’s demands and more like a treatise on human rights. If there is any takeaway from the symptoms the platform addresses, it is that this fight is not just about the problems on a single campus.

Despite this, in most local media coverage of the strike, pay has become almost the sole focus. This is because of how the university is framing the discussion around money.

Under their “Facts of Compensation,” the U of M’s press release and updates on the strike show a clear demarcation between the hourly wage to meet Ann Arbor’s cost of living ($18.67/hour) and what graduate students in the GEO make today ($35/hour). The same graph shows what the university has offered as its counteroffers ($37/hour and $39/hour). When put side-by-side with what the GEO workers have proposed ($55/hour in the first year), it’s no wonder that the demands might come off looking unreasonable.

Despite claiming that they remain “ready and willing” to negotiate, however, the university does not want to address the fact that graduate students tend to only bill 16-20 hours a week, despite working well above the 20-hour mark. The GEO’s demand of $55/hour needs to be understood in the framework of part-time work rather than the university’s implied 40 hours or more.

When calculating a salary of $38,000 down to an hourly wage, graduate students not-so-surprisingly only make $18.27/hour.

What’s next

Although there is a disparity between faculty and students, plenty of faculty have voiced support for the striking students. In fact, when it comes to most workplace demands, it’s important to remember that many students will earn their degrees and move on. The faculty will more than likely remain and be vulnerable to colleagues with histories of harassment, assault, or racism.

Perhaps this shared struggle has not been completely overlooked. Between the recent strikes at Rutgers University and Chicago State University, and the graduate students of the University of Chicago and undergrads at California State University voting to unionize, college campuses are in the spotlight this season.

Although much of the reporting has focused on living wages, there is more to be won in this wave of organizing. Many grad student unions have platforms that include proposals completely unrelated to pay, but the fact that these provisions do not garner attention should not lead one to conclude that they will be accepted or, worse, do not matter.

Not only does the GEO’s bargaining platform at the University of Michigan stand as a model for unions to come, but it also shows how fully politicized both the role of worker and the role of student actually are. The issues graduate workers are up against speak to this political relationship.

Often, universities hesitate to make big policy changes due to legal obligations and liability from federal laws such as Title IX and federal guidance. So it is with bargaining contracts that these workers are able to articulate and even win what is needed to affect larger, institutional changes.

From this perspective, it is important to note not only the victories students may gain regarding a living wage but also what the universities fear giving up: Power.

Comments