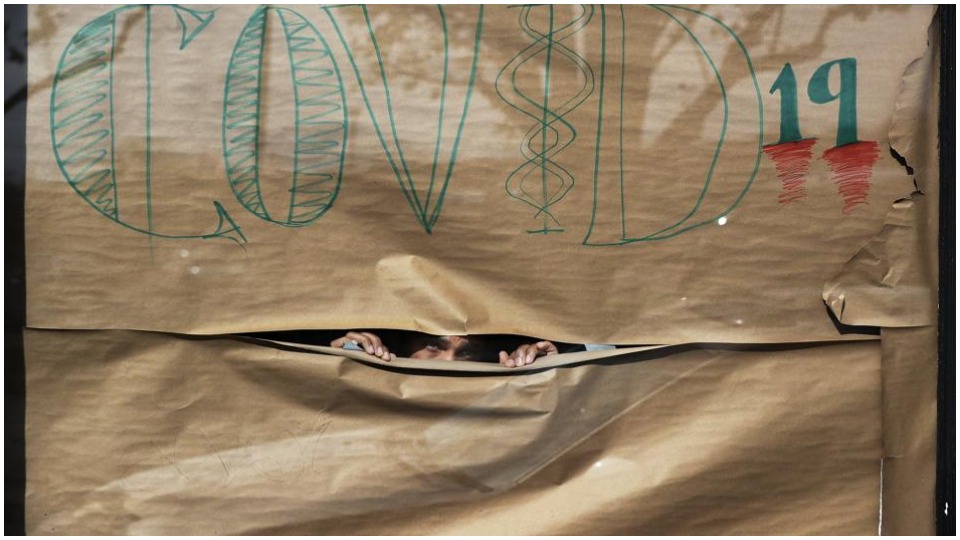

In terms of health, the coronavirus is undoubtedly one of the greatest challenges in recent history. But it may also turn our economic system upside-down completely. It is already clear that in future we will look back on 2020 as a turning point, the beginning of a new era.

COVID-19 is an unusually aggressive virus, the most serious seen in a respiratory virus since the “Spanish Flu” of 1918 when at least 20 million people died. We do not yet know how long this pandemic will last. For weeks, months, or longer? Will it reappear after summer?

The prestigious Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota states that we will have to maintain measures of “social distancing” for 18 months, or until a vaccine is available. Experts from Britain and the World Health Organization confirm this. The development of such a vaccine is likely to take between a year and 18 months.

The coronary shock on a weakened body

The containment of the pandemic will thoroughly disrupt economic life. Entire branches of the economy are being shut down: all human-contact industries, sectors such as the automobile industry, large parts of the service sector, and so on. In addition, the economic engine is slowing down due to the decreased purchasing power of the population as a result of the sharp increase in unemployment.

As we know, in most cases a healthy and strong body is more immune to the coronavirus. COVID-19 becomes especially dangerous and deadly for the weakened or the diseased. The same goes for the economy. In principle, a healthy economy might be able to cope with the corona shock. But that precisely is the problem.

Productivity growth (the amount of wealth a worker produces per hour) is a good indicator of the health of the economy. Over the last 20 years, it is precisely productivity growth that has almost come to a standstill. Companies invest less and less in expanding and renewing their production capacity. Instead, they use their profits to buy up their own shares, and they pay dividends more than before.

Profit rates (percentage of profit on invested capital) are also a good indicator. Here, too, we have seen a steady decline since the 1970s.

Another indicator is debt. In 2018, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) warned of the vulnerability of the world economy because of the high global debt burden. Worldwide, the total mountain of debt has reached a record amount of $253 trillion. That is 322% of world GDP.

The cause of the 2008 crisis was the overuse of “subprime mortgages.” Now it is high-risk loans to private companies—and this involves much larger sums of money. For Asia alone, the payout of as much as $32 trillion of debt is at risk. That amount is about the same as one-and-a-half times the total GDP of Europe.

COVID-19 will deal our economies a heavy blow. But it is not to be blamed for everything. Sooner or later a serious blow was imminent. The coronavirus is too much of a shock to the already weakened economy.

The best possible scenario

The decline of stock markets and the collapse of oil prices may be a taste of what’s in store.

In China, the country that was first hit, but which also took sweeping containment measures very quickly, the lost output is expected to be 5% this year. For the U.S., an annual contraction of 7.5% is to be expected if the crisis lasts three months. For Europe, a 10% fall in GDP is already taken into account. The eurozone jobless rate could rise from 7.4 to 12% by the end of June. Some U.S. predictions go as high as a 30% unemployment rate, surpassing Great Depression levels.

Everything depends on how long the health crisis will last. If that is two or three months, then we are dealing with a temporary suspension of production. That will hurt, but with sufficient support measures, such a period can be bridged.

In the best case—without any financial complications—it is possible to restart production as before and recover the costs in the usual way, i.e., on the backs of the working population. This would be a scenario comparable to that of the period after 2008.

As a reminder, the 2008 crisis had devastating effects. More than 20 million people lost their jobs and 64 million people worldwide were pushed into extreme poverty. The crisis hit government budgets and cost eurozone countries 20% of their GDP.

Other possible scenarios

Another very real possibility is that the health crisis will last longer in some of the countries with the biggest economies. The Financial Times assumes that the impact will be “severe and prolonged” and that “the world might not return to pre-crisis behavior until well into 2021.” In that case, many companies will not survive the crisis and go bankrupt.

Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, former and current chairpersons of the U.S. Federal Reserve, warn that in such a scenario the economic fabric will be severely damaged and the recovery will take a very long time. There will not only be a temporary suspension of production but a rearrangement of the entire system.

That realignment will come on top of the shifts caused by Brexit and the U.S.-China trade war.

But there’s more. Reuters news agency points to the fragile situation of the financial markets and states that, in such a scenario, the entire financial sector threatens to be dragged down into the mire. If that were to happen, the consequences would be catastrophic. In 1980, the total value of financial markets was about the same as the real economy. Now it is four times larger.

In addition, there are hardly any barriers between the various sectors of the financial world. If one part is affected, the crisis spreads like a virus over the whole. Such a financial tsunami could cause large parts of the system to collapse.

Beyond financial doping

In order to absorb an immediate shock, monetary measures such as bridging loans, loan guarantees, forbearance, spread of payment, etc. are needed first and foremost.

But in order to keep the markets stable, a lot of money is being pumped into the financial markets today (so-called “quantitative easing” or QE). That in itself shows how shaky and absurd our economic household has become.

QE can actually be seen as a kind of doping, a temporary boost for the patient, but one that only makes them sicker in the long term. QE, along with very low interest rates, has led to a massive financial bubble and to today’s many “zombie” banks and companies.

Our financial system is completely diseased. No fewer than 147 individual national banking crises occurred between 1970 and 2011, according to the IMF.

It’s time to put the banking system in government hands and to dismantle casino capitalism. In this way, we can save ourselves perverse financial crashes and invest our savings in a social and sustainable way.

Never waste a good crisis

In order to maintain purchasing power and to prevent companies from going bankrupt, fiscal measures are urgently needed: direct support for families or companies.

This could be in the form of providing cash to families, canceling energy bills, supplementing unemployment benefits, bridging funds for businesses, temporarily canceling taxes, and similar measures.

In Singapore, all adults receive a monthly sum of money. In Hong Kong, the majority of residents receive $1,280. In the U.S., Bernie Sanders wants to pay $2,000 a month to all families until the end of the crisis. In Canada, the government of Justin Trudeau is doing just that for those put out of work by the pandemic.

Once the emergency measures have been relaxed, fiscal measures can also take the form of big government projects and assignments. They can offset lost economic growth and absorb increased unemployment. There is no shortage of potential candidates for such projects.

For example, this crisis has revealed that healthcare in many countries could use a serious investment. The same goes for a lot of other sectors. And of course, there is global warming. The coronavirus crisis is the perfect time to launch a Green New Deal (GND). We are talking about a real GND, ambitious enough to save the planet and not just safeguard the profits of the big companies.

If the crisis continues for a long time, a thorough realignment of the entire economy will be imposed anyway. For the time being, most countries in Europe want to spend barely 2% of their GDP. In Germany on the other hand, it is 4%, and in the U.S. 5%.

It is assumed that 5% is needed to overcome the crisis. Financial Times chief economist Martin Wolf has clear advice: “In war, governments spend freely. Now, too, they must mobilize their resources to prevent a disaster. Think big. Act now. Together.”

Who is going to pay?

The big question is: Who is going to pay?

It would be unacceptable if the crisis were passed on to ordinary people again. The fiscal measures can be financed in three ways: by taking on debts, by printing ordinary money, or by activating dormant capital.

Taking on new debts, such as in 2008, will result in a new round of austerity. We must vigorously oppose this. Even Rana Foroohar of the Financial Times thinks this is reckless: “If we want capitalism and liberal democracy to survive COVID-19, we cannot afford to repeat the mistaken ‘socialize the losses, privatize the gains’ approach of a decade ago.”

Printing money to stimulate the real economy is an abomination to neoliberals and is even forbidden in Europe. But the coronavirus crisis is an excellent opportunity to break that dogma. According to Paul de Grauwe of the London School of Economics, this measure is even necessary to keep the eurozone together.

The third way is also obvious. Forty years of neoliberal policy means that wealthy individuals and large companies today have so much “surplus of capital” that they don’t know what to do with it.

It is these trillions of dollars that they park on tax havens. It is time for a real coronavirus tax—targeting the super-rich.

We can learn from the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius here. Faced with a pandemic from the year 165 CE onwards, he confiscated capital from the aristocracy. The common people were given money to pay for the funerals of the pandemic victims.

In times of crisis, we must dare to think and act boldly. Milton Friedman, one of the high priests of neoliberalism, already knew it: “When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.”

It is up to us to put forward the good ideas.