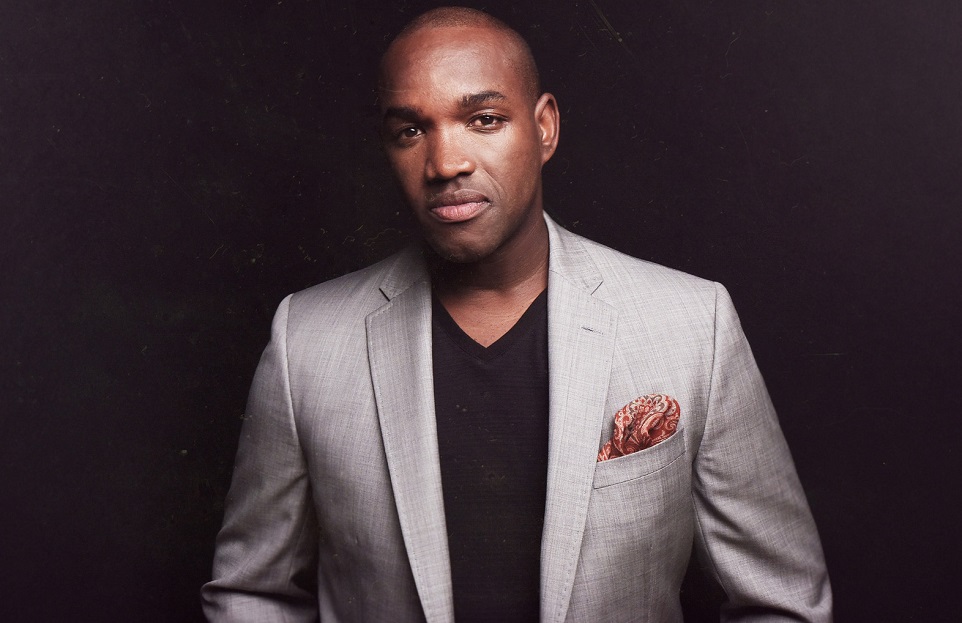

Internationally heralded tenor Lawrence Brownlee specializes in bel canto and coloratura roles. This season he appeared in Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte at the Metropolitan Opera. But for his new CD he has shifted gears. “These past years have been a trial,” he says, “both for humanity as a whole, and the African-American population here in the United States. But through all these many challenges we have faced, I have also seen moments of strength, inspiration, hope, and great beauty. It is those themes of uplift, elevation, and rebirth that we have tried to focus on with this new project Rising, taking poems from the giants of the Harlem Renaissance, and working with some of today’s most talented African-American composers, to create something that speaks not just to our struggles, but to our triumphs.”

Brownlee includes three rarely performed song cycles by two revered 20th-century African-American composers, Robert Owens (1925-2017) with his Desire and Silver Rain, and Margaret Bonds (1913-1972) with her Songs of the Seasons. The texts to all these songs are by Langston Hughes. It’s a joyful event to rediscover these works.

But Brownlee has extended his reach, commissioning five up-and-coming African-American composers to set poetry from the Harlem Renaissance (mostly the 1920s and ’30s) that evoke themes of empowerment, faith, and love in the face of profound societal challenge. Additionally, Jeremiah Evans has three songs on the CD.

Brownlee is accompanied throughout by pianist and collaborator Kevin J. Miller, who also appeared with the singer on a nine-city pre-release concert tour of Rising, which included stops in Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and New York City.

Let’s briefly talk about the Bonds and Owens songs before moving on to the new work. Bonds starts with autumn and moves through the four seasons, ending with summer. In “Winter Moon” Bonds introduces some audible homage to “Oriental” music, perhaps summoning the fascination many Asian cultures exhibit with lunar contemplation. “Young Love in Spring” bathes in the joy that “spring has come once more,” and it’s all you’d ever want a sprouting spring song to express. In the forceful “Summer Storm,” which sounds like the poet’s sweet romantic memory, we hear the rumble of a sudden July thunder echoing the thunder “in my heart”: “The wonder of love, thunder, wonder in our eyes:/the wonder of being in love./We two, the wonder of being in love with you.”

In Desire’s four short poems with the titles “Desire,” “Dream,” “Juliet” and “Man,” Owens interprets Hughes’s short, enigmatic ruminations on love. It’s in the last one that Hughes leaves his youthful infatuations behind as he comes of age. Its complete text reads:

I was a boy then I did not understand I thought that friendship

lay in the grip of hand to hand

I thought that love must be her body close to mine

I thought that drunkenness was real in wine.

But I was a boy then, I didn’t understand the things

a young lad learns so soon, when he’s a man, a man, a man.

And in Silver Rain, its seven short songs touching on nature and times of the day, love and song, “Carolina Cabin,” referencing “hanging moss” and “tall straight pine” and musically capturing the harmonies of the Old South, also hints at Jim Crow oppression and the succor provided by love and the simplicity of home. Its last two lines read: “Outside the world is gloomy, the winds of winter cold, as down the road a wandering poet must roam./But here there’s peace and laughter and love’s old story told where two people make a home,” followed by a luscious humming that could mean a tender hour or two of lovemaking. I’m drawn to this interpretation because the sixth song, called “Songs,” reads, “I sat there singing her songs in the dark./She said, I do not understand the words./I said, There are no words.” And the last song, “Sleep,” clinches the meaning: “When the lips and the body are done she seeks your hand, touches it, and sleep comes without wonder and without dreams.”

Audiences should hear more from Margaret Bonds and Robert Owens!

As the CD ends, so it begins, with the first of Brownlee’s commissions. Here too, in Damien Sneed’s (b. 1979) “Beauty That Is Never Old,” the poet James Weldon Johnson of “Life Every Voice and Sing” renown, contrasts “the bitter tears of life oppressed” with “no sweeter heaven than your breast.” Sneed’s three-song contribution is all set to Johnson’s lyrics. In “The Gift to Sing” Johnson expands on his contrast between “blackening clouds” and “gloom” on the one hand and the theme of the song:

I brood not over the broken past,

Nor dread whatever time may bring;

No nights are dark, no days are long,

While in my heart, there swells a song,

And I can sing.

And in the last of the James Weldon Johnson group, the poet issues a challenge “To America,” with lyrics powerful enough that the CD booklet, which contains all the lyrics to all the songs, recapitulates these verses on its back cover. Though Johnson represented his own African-American people, today we can read his particular rebuke as the cry of every group universally being held down by patriarchy and offering the nation a better, unfettered future:

How would you have us, as we are?

Or sinking ’neath the load we bear?

Our eyes fixed forward on a star?

Or gazing empty at despair?

Rising or falling? Men or things?

With dragging pace or footsteps fleet?

Strong, willing sinews in your wings?

Or tightening chains about your feet?

Jeremiah Evans (b. 1978) contributes three numbers, “April Song” (about rain, lyrics by Langston Hughes), “Lost Illusions” (about “the veils of my far away youth…that hung low o’er the blaze of the truth,” lyrics by Georgia Douglas Johnson), and “Southern Mansion” (lyrics by Arna Bontemps), whose reference to poplar trees inevitably recalls the Lewis Allan song “Strange Fruit”:

Poplars are standing there still as death

And ghosts of dead men

Meet their ladies walking two by two beneath the shade

And standing on the marble steps.

There is a sound of music echoing

Through the open door

And in the fields there is another sound tinkling in the cotton:

Chains of bondmen dragging on the ground.

The years go by with an iron clank,

A hand is on the gate,

A dry leaf trembles on the wall.

Ghosts are walking.

They have broken roses down

And poplars stand there still as death.

The song ends with a piano coda of jazz-inflected invention.

Brandon Spencer (b. 1992) is up next, with two songs, with lyrics by Claude McKay and Countee Cullen, whose “Dance of Love” recaps a night of ecstatic lovemaking, followed by blessed sleep.

Joel Thompson (b. 1988) selects three poets for his songs—Joseph Seamon Cotter, Jr. for “Supplication,” Paul Lawrence Dunbar for “Compensation,” and Langston Hughes for “My People,” which is one of the high points of the CD, a catalog of the types of individuals encountered among his beloved African-American community. Most of all, amongst the singers and dancers and storytellers, he celebrates the laughers, yes, the “loud-mouthed laughers in the hands of Fate—My People!” Thompson’s score sets cascades of “hahahas” to music that flatters Brownlee’s coloratura capabilities.

Jasmine Barnes (b. 1992) also relies on Georgia Douglas Johnson for her first song, “Peace,” with its updated Beethoven’s 9th sentiment:

Peace, on a thousand hills and dales.

Peace, Peace in the hearts of men

While kindliness reclaims the soil,

Where bitterness, where bitterness has been.…

Forth from the shadow, swift we come

Wrought in the flame together.

All men as one beneath the sun

In brotherhood forever

(ooh) Peace (ooh)

Which gives the singer once again ample opportunity to display his detailed vocalism. The inclusion of wordless sounds in this and other songs on the CD is not especially remarkable in and of itself—it’s hardly uncommon in music—but here would seem, at least some of the time, to recall the keening associated with African-American sorrow.

In her second song, “Invocation,” to another Claude McKay poem, she addresses her Ancestral Spirit from ancient, pre-Biblical Ethiopia “before the white God said: Let there be light!” “Lift me to thee out of this alien place,” the lyric reads, the singer sings, “So I may be thine exiled counterpart,/The worthy singer of my world and race.” Barnes infuses this pan-African song with “Eastern” music tonality, even maybe a little Jewish.

Shawn E. Okpebholo (b. 1981) also goes to Claude McKay for “Romance,” again with deliciously voiced “ah…ooo…ah…ooo..mmm…” The poet apostrophizes an anonymous “you” with “Love words, mad words, dream words, sweet, sweet oh, sweet words, senseless words,” ending with almost a literal invitation to some future composer: “The poem with this music is complete.”

McKay (1889-1948) never “came out” in the modern sense but was known to be bisexual. The poem “Romance” gives no hint as to the gender of the writer’s object of passion. He traveled to pre-USSR Soviet Russia in 1922 to address the Third International with a “Report on the Negro Question” at a time when what we would call LGBTQ liberation was official policy there. His 1933 novel Romance in Marseille, too radical for its time but posthumously published only as late as 2020, is the fictional story of a Nigerian man who, once he receives reparations from a shipping company for his forced imprisonment at sea, moves to a land where he can live in a society that views homosexuality and heterosexuality equally.

Rising is a rich, juicy, evocative collection of songs performed to perfection. As a final observation, I would only comment that we seem to have passed the era when Black composers felt they had to, or were expected to, “compose Black.” They can choose any idiom or esthetic they prefer, which may or may not reference the rhythms, riffs, and blue notes of African-American culture. Many—but to be sure, not all—of this CD’s songs exemplify the contemporary state of art song composition almost in a purposeful manner not to be pigeonholed as “Black” music. Still, there is a goldmine here of Black influence, both musical and literary, that is inextricably part of the larger American culture.

For further information on Lawrence Brownlee see his website.

Rising

Lawrence Brownlee, tenor

Kevin J. Miller, piano

Warner Classics 5054197563713

Timing: 65:45; released June 2, 2023.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments