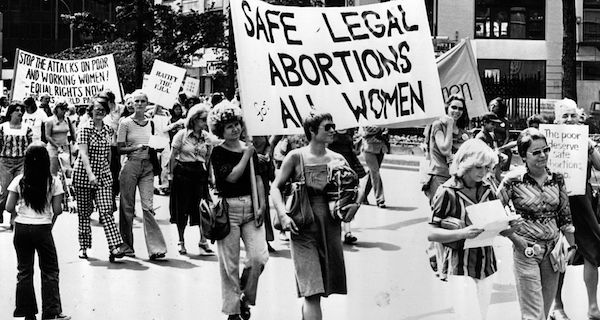

On Nov. 7, Ohioans will vote on Issue 1, which would establish a state constitutional right to “make and carry out one’s own reproductive decisions,” including decisions about abortion, contraception, fertility treatment, miscarriage care, and continuing pregnancy. Free access to birth control, including abortion when necessary, is a fundamental prerequisite to the emancipation of women and, therefore, all working people.

To contextualize this vote within the history of the struggle for reproductive rights, People’s World has collected three previously unpublished personal stories. Each one addresses an individual woman and her experience in obtaining reproductive care, as well as the impact of the prevailing laws at the time on her decisions and treatment.

These stories reflect both the hardship and resilience of working-class women and the social networks that supported their personal resistance to a particular form of persecution endured by women under capitalism—the limitation of reproductive autonomy.

I. Underground abortions

“Mary” was a student at the University of Michigan when she learned she was pregnant in 1968. She provided this account of her abortion in her own words:

The doctor at the health clinic who told me I was pregnant asked if I was considering hurting myself (suicide). If so, she could do something, but otherwise she gave me the name of a person in an underground network of clergy. I contacted him, and he gave me the name of a doctor in Ohio. I can’t remember the town or name.

I then drove to Ohio with Tom, the father. The abortion cost $500. I had $520 in my purse. They took me in and prepped me for the procedure. I then had to wait on the table for about an hour until the doctor came in. When he arrived, he was smoking a cigar. He was curt and demanded the money for the procedure. I told him $520 was in my purse and that he better not take the extra $20. He took the money and then did the procedure.

I was given no anesthetic. It was very painful. When I left I told Tom that I wanted to find a patch of grass so I could lay down and die. Needless to say, he was pretty freaked. We sat on a patch of grass for a while and then drove back to Ann Arbor.

My health center doctor had asked me to come back afterwards so she could make sure that I was ok, which I did. I was a lucky one—no complications, good pre- and post-medical care, a boyfriend who was willing to pay for the abortion and go with me as well. The $500 would now be the equivalent of about $4,000.

My outcome was good, but I know that most women didn’t have that kind of support. I realized later that the doctor left the extra $20 in my purse, and I was surprised that he didn’t take it.

Many women seeking illegal abortions pre-Roe obtained them from a secret unsanctioned group. The most successful of these networks, the “Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation,” was created in 1969, and became known as The Jane Collective.

It was comprised of volunteers who helped women understand abortion procedures and obtain safe abortions. It eventually published a flyer describing the procedures and provided approximately 12,000 abortions in the United States before the procedure was legalized in 1973.

The primary concern of the Jane Collective was ensuring safe abortions. Shortly before the Jane Collective was formed, a Connecticut woman had died at the age of 28 when she tried to self-induce an abortion following guidelines in a textbook. Many other women also suffered “botched abortions,” that were incomplete, damaged internal organs, or led to infections or hemorrhaging.

In 1972, the Jane Collective was “busted,” and seven of its members were imprisoned. During the resultant public attention and outrage, the United States Supreme Court decided Roe, and their charges were dropped.

II. Overseas abortions

When Cara suspected that she might be pregnant, she was a junior in high school living with her parents. Cara’s doctor was a family friend she had known since she was a toddler and a person whom she felt she could trust.

During the office visit, the doctor conducted a pregnancy test and confirmed that she was pregnant. Cara strongly believed she was incapable of raising a baby while in high school. After she explained this to her doctor, he told her about a clinic in England, where abortion was legal.

Cara confided in her mother, but they both decided to keep her pregnancy secret from her father, even though he was close friends with her doctor. Cara’s mother gathered sufficient funds for Cara and Dan (the father) to fly to London, obtain an abortion, and stay in a hotel the night before and following her procedure. Cara now describes the experience and procedure as brief and without complications. Her primary feeling was relief.

Abortion had been legalized in the United Kingdom by the Abortion Act, which was enacted on April 27, 1968. The Act allowed abortions up to the 28th week of gestation if the pregnancy presented a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or a risk of grave permanent injury to her physical or mental health.

The Act also permitted abortions when there was a substantial risk that, if the child were born, he or she would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped. Most abortions—98%—were conducted because of a risk to a woman’s mental health.

The number of abortions declined significantly in the United Kingdom after abortion was legalized in New York and later upheld in Roe v. Wade. In the United States in the 1970s, agencies were created prior to the Roe decision that offered four-day trips to England for American women seeking legal abortions. These agencies met the women at the London airport, paid for their hotel and meals, and performed the abortions at a private clinic.

This, of course, was a service only available to a small number of women relative to those who needed access to reproductive health care.

III. New York abortions

This is a summary of “Angie’s” experience with abortion in 1970.

She had just returned to college as a sophomore that fall after staying with her parents during the summer. She lived in a dormitory with two other women with whom she spent most of her time.

Angie had recently started dating Andy, who was also a sophomore at the college. Because of the dormitory’s strict curfews, Angie and Andy’s dating activities were limited. They typically dined out before attending a movie and then would go “parking.”

Andy lived off campus in an apartment. One night, when his roommate was gone, Andy invited Angie over for dinner and they had sex for the first time. A few weeks later, during a late-night conversation with her roommates, Angie shared that her period was late, and she feared she might be pregnant, even though she thought that she and Andy had had “safe sex.”

Angie and her roommates decided that she should have a pregnancy test if she didn’t start her period in a few days. Angie felt increasingly frightened because her family were staunch Baptists, and sex before marriage was strictly forbidden. She also was upset because she learned that Andy had slept with another woman after he attended a party with friends.

Angie was shaken when her pregnancy test was positive; she felt shocked and panicky. She did not want to have a baby until she was married, and her relationship with Andy was collapsing. If she took time off from school, had the baby, and gave it up for adoption, an option about which she was deeply conflicted, she would have to tell her parents, who would be livid and severely disappointed in her.

Her roommates wanted to help. One of them called an older sister living in New York City, where abortion had just become legal, and she arranged for Angie to have an abortion there. Angie’s roommate accompanied her on the flight to New York, where they stayed with her roommate’s sister, and she had an abortion the next day.

Abortions were legalized up to the 24th week of pregnancy in New York in 1970. New York was the second state, after Hawaii, to legalize abortion, but unlike Hawaii, New York did not have a residency requirement. Not surprisingly, New York became one of the prime locations for women to have an abortion during the 1970s. Approximately 100,000 women traveled to the state in 1972 alone to obtain an abortion, with most of them traveling more than 500 miles to get there.

In addition, New York provided Medicaid funds for low-income women to pay for their abortions, which cost about $175 in the late 1960s. When the Hyde Amendment was passed by Congress in 1976, states were prohibited from using federal funds for abortions except in cases of rape or incest. This amendment prevented many low-income women, and especially women of color, from obtaining abortions. However, New York became one of the few states to offset this law by using state funds to pay for abortions.

IV. The impact of “the pill” on abortion

Like Angie, “Valarie” suspected that she might be pregnant the month before she was to return to her sophomore year in college. Valarie became so anxious about the possibility that she finally confided in her mother, who was surprisingly sympathetic and understanding.

Although her mother suggested they see a physician to test whether she was pregnant, Valarie decided she would go to the health clinic at her school because she didn’t want her father to know. Meanwhile, Valarie’s mother told her that she herself had attempted to induce a menstrual period or a miscarriage many years earlier and believed she had succeeded by “jumping up and down.”

Valarie and her mother jumped up and down every night hoping this would either start her period or end the pregnancy. A few weeks later, Valarie returned to college and had a pregnancy test at the health center, which showed that she was not pregnant. The doctor prescribed the birth control pill for Valarie; it had just become available on American campuses in 1970.

In the 1900s, the United States was the only Western nation that outlawed birth control. Congress passed the Comstock Act in 1873, which outlawed the dissemination of contraceptives as obscene material. When Margaret Sanger was indicted under the Comstock law for using the term “birth control” in a magazine, she fled to England.

The charges were later dropped, but she was arrested again when the first birth control clinic in America—which she created—was raided and shut down. The latter charges against Sanger resulted in the Crane decision in 1918, which was the first American legal ruling to allow birth control for therapeutic purposes.

But it was another 30 years before a new form of birth control was announced in 1955 and approved by the FDA in 1960: “the pill.” By 1963, 2.3 million American married women were using the pill despite laws prohibiting the sale of contraceptives in some states.

In 1965, the fight went to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled by a vote of 7-2 that state prohibitions against birth control violated couples’ right to privacy. However, the use of the birth control pill by single women was not legally protected until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on the issue in 1972.

The impact of the birth control pill on American women was revolutionary: It meant that women had control over their potential pregnancies and did not have to only rely on a partner to use contraception. Women acquired more control over their personal life goals, including education, employment, careers, and lifestyle.

Despite the availability of the pill, many women continued to have underground abortions. It was not until the United States Supreme Court ruling in Roe v. Wade in 1973 that state laws banning abortion early in pregnancy were deemed unconstitutional.

When Norma McCorvey, referred to as “Jane Roe” to protect her privacy, became pregnant with her third child in 1969, she was unable to obtain an abortion in Texas. After the district court ruled in her favor, the local district attorney appealed the decision to the United States Supreme Court. Its ruling in favor of McCorvey meant that every woman in the United States had the right to an abortion within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Vote yes on Issue 1

Ohio voters will soon decide whether women have a constitutional right to make their own reproductive decisions, a right that was protected under Roe in 1973 but taken away by the right-wing Supreme Court last summer.

The proposed constitutional language in Ohio’s Issue 1 referendum protects women who seek to terminate a pregnancy from potentially catastrophic experiences like those of the women exemplars presented here.

A vote of “no” would return the state to a time when a woman who sought to terminate her pregnancy would need to seek illegal underground abortions, travel to another state, or risk her life by attempting to self-abort.

The adverse consequences of outlawing abortions place particular hardships on women who lack sufficient resources to travel to have an abortion.

For all these reasons, it is imperative that Ohioans vote “yes” on Nov. 7.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments