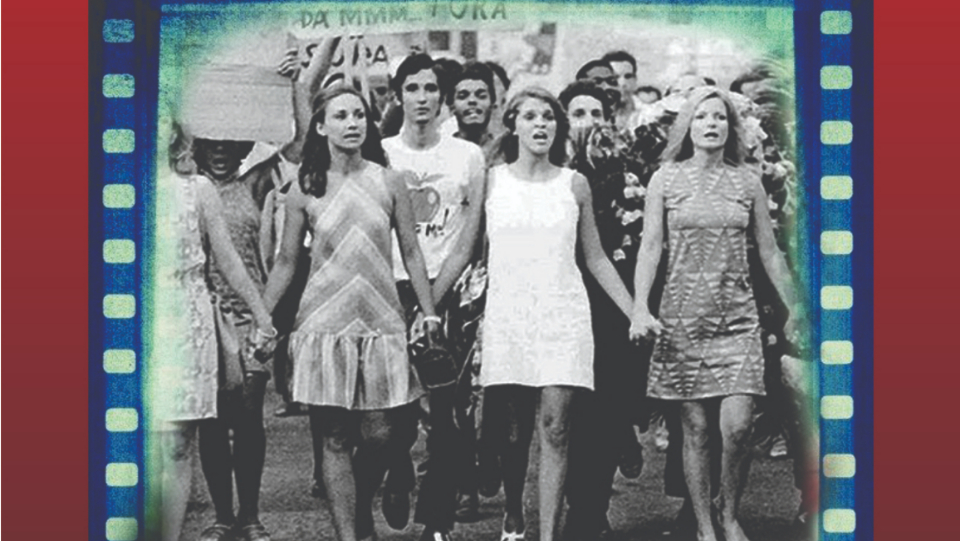

People’s World readers are invited to sit back and enjoy the exuberant writing in “Open Your Window,” a chapter from the recently published novel Never-Ending Youth, about the young student generation in its resistance against the Brazilian military régime in the early 1970s, introduced here by the translator Peter Lownds. He begins his introduction with an evocative 1962 poem by renowned poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade, which he translated for this article.

Finishing Touch

The prodigal son returns

to his father’s house

and his father is dead since Adam.

Where there were clocks

and rocking chairs

cows fertilize the surface.

The prodigal feels his way along

whistles intuits summons up

the eighteen reasons he fled

and nothing else stirs

not a sob.

There are no reproaches or pardons,

no one opens a door.

What happened no longer matters

in the absence of faithfulness

and betrayal.

Thrown on a green dung heap

the gramophone’s needle

sweeps from opera to empty.

The ex-prodigal son

loses his reason to be

and spits

in the totally dry air.

Urariano Mota, the author of Never-Ending Youth, is a novelist and journalist who was born and raised in Água Fria (Cold Water), a hard-scrabble suburb of Recife, Pernambuco. The son of a distant, longshoreman father who spoke fluent English and a loving white mother who died when he was five, Urariano was spellbound by poetry as a youth. Carlos Drummond, one of whose poems appears above, was a major influence. Native sons Manuel Bandeira and João Cabral de Melo Neto were others. Cabral’s Morte e Vida Severina (Death and Life of a Severino) won international recognition for the poet in 1966 when singer/composer Chico Buarque brought it to the stage and in 1977 when a film version was released. Urariano acknowledges these poetic forebears as important as his Marxist-Leninist roots. The young revolutionaries whose lives he follows in Never-Ending Youth struggle to make and maintain ties with the common people. They see themselves as some of “the many Severinos/all with the very same life” that Cabral describes in his epic. Urariano Mota’s novel is filled with poets and poetry because he believes, as does Cabral, that a poet’s richness “can only originate in reality.” The reality of Never-Ending Youth is dark and uproarious. It is also directly linked to what is going on today in a country with triple the population of the Brazil that Uraniano and I remember from the late 1960s and early 1970s.

That is why I cite and translate Carlos Drummond’s poem Remate (pron. heh-mah-chee), or “Finishing Touch.” On October 2, 2022—three short months from now—Brazilians will go to the polls to decide not only the fate of their country but the fate of the planet. If incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro is reelected, or stages a violent coup as his acknowledged mentor Donald Trump attempted, we will all be “prodigal sons” and daughters watching as—for the sake of hamburgers über alles—“cows fertilize the surface” of what used to be the Amazonian rain forest. Drummond’s words, written sixty years ago, are haunting: “What happened no longer matters/in the absence of faithfulness and betrayal.” Bolsonaro’s betrayal of the treaties that guaranteed the sanctity of the Indigenous Territories as a sanctuary for the million autochthones who survived his heartless, murderous weaponization of COVID and throwing open the gates of the trans-Amazon and the Xingu Reserves to the property deed-forgers, miners, fishers, hunters, cattle-ranchers, deforesters, and the transnational Mafia that supports them, means that all of us have been “Thrown on a [formerly] green dung heap.”

Support art! Support culture! Support People’s World and International Publishers! Support literature in translation! In the following sample chapter of Never-Ending Youth, I have removed four expository footnotes, which I’ve marked only by placing the references in italics.

__________________

Open Your Window

How do you listen to Ella Fitzgerald without a record player? I know that question will recur often in this story of recuperation. I wonder why? I do not know the answer, but I search for it. I look for it as I looked for my friend the terrorist’s face on a poster in 1970. Ironically, although I have no phonograph, the Party owns a mimeograph for which I am responsible, a far more expensive and dangerous piece of machinery. Do Carmo, it has been decided, will share the humble room where I am apparently sentenced to serve out all the days of my youth. You will hear about the mimeograph presently, but first I need to describe my previous abode, the May 13th Pension on Princess Isabel Street. Even a novelist would not think to link the anguish of the military dictatorship with Princess Isabel and May 13th. But reading history can be more ironic than recreating it. God, what miseries I have endured! Those were my thoughts when I revisited the building, recently. The bedroom was suffocating. I imagine prison cells are similar. What the greedy landlady called “a house” was tinier than a garret. Its location at the top of a steep flight of stairs was ideal for a hideout. However, it was literally a rattrap. I shared it with a sizable colony of rodents whose constant turmoil I witnessed through a trellis illuminated by the sole electrical fixture, an incandescent 40-watt lamp. My only advantage derived from the steep slope of the roof which provided some headroom at its vertex. The dimensions of this hovel were barely enough for a bed and the tiny living room I shared with the watchful rats. I needed a meter to open the door and flop on the straw-filled mattress. The roof looked as if it were about to cave in. As for my clothes, some stayed in a suitcase, while others were spread out on the floor or hung from a meter of frayed cord I found on the street. These details are painful to recount but true.

Because it prevails, shame must be talked about. I tried to make a poem of it—“heat hell cell low anguish hellish”—but this word string could not convey the extent of my misery in that abode. Inside the “room,” I perspire constantly because there are no windows for ventilation or from which I could view the Capibaribe River across the street. My rodent roommates multiply when the Capibaribe floods its banks, as it does often in wet winters. Only a shard of a mirror reminds me that we are of different genera. When I look in the mirror, I do not like what I see—a furious expression on a permanently agonized face that melds ugliness with anguish—the consequence of my struggle to dig myself out of this hole. One night, suffering from an intestinal crisis with no strength to descend to the communal bathroom, I cut the cord that served as a clothesline because it inspired suicidal thoughts. With that bit of rope, there was no way I could act on them even though I felt driven to do so. Lacking all other options, I wrote a horrible tale I called “The Pendulum,” a half-assed homage to Poe, in which I imagined my pendant body rotting. Shame restrains me, momentarily, from admitting I slept naked in the intense heat as I could not afford an electric fan. Spit it out! What was left? Only the family jewels, scrotum and testicles. I wanted to protect my sexual future. From what, for God’s sake? From the rats, who watched me intently. I imagined them voraciously feeding on my patrimony. So, even in the intense heat, I slept with the sheet wound round my genitals. Let them come, let them scamper over my body, they would not end my lineage!

The cuts I would have played first on my Ella album were “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” and “Open Your Window.” Open your window, young man! She was blind to my present dilemma, but I knew she cared. “I Wonder Why” was my anthem. I needed to know the reason for my dismal state. Conflict is caused by what we most desire for the simple reason that we do not have it. Anguish about my lack of options grew with every wretched day that passed. Unresolvable situations magnify dissatisfaction. “Open your window!” Ella would sing if I had a victrola. The liner notes describe it as “a song of absolute antagonism.” I resolve for once and for all to end this misery and, moments later, Luiz do Carmo knocks, enters my lilliputian surroundings and says:

“Selene wants to meet with you.”

“When? Where?”

“Right now, at the bar next door.”

I go downstairs. The sun drops as it does in these climes, like a curtain. The bar next door is part of a decaying restaurant, a late-night place like a lot of joints near the docks which caters to sailors and stevedores. Women are unwelcome. In 1970, gender apartheid is endemic. Selene, a lioness of transgression, is assumed to be a puta. She provokes the curiosity, vigilance and lust of the clientele who remain nailed to their seats. Besides, she is protected by her escorts, Luiz, Célio, and Alberto, stalwart militants all. Her retinue of reverently attentive young men make her specialness clear. Every time she speaks, the dingy barroom is illumined and her guards blink and gather closer. Her beauty is of a different order. Her spontaneous gestures, whimsical spirit, unbridled affection, inspiring ideas and capacious heart are more memorable than her looks.

Go ahead, describe her face, I dare you. Selene is fair, her eyes light brown, her hair parted in the middle. Sometimes she ties it back with a rubber band or a bit of ribbon as is appropriate for an unselfconscious maid of the proletariat. But to limit your gaze to her face is impossible. The masculine gaze takes in the totality, is concerned with the sum, never the detail. Did Selene have breasts? Naturally, as firm and as succulent as ripe mangoes. But they were never very visible, not even when she wore a blouse. I recall that she rarely if ever wore lowcut tops. But Selene the woman vanquished Selene the warrior. She illustrated her talks with animated gestures. Her arms were tapered with delicate wrists and slender hands. What about her fingernails, did they suffer from neglect, as would be appropriate for a radical? I cannot recall. And her neck, was it smooth? Yes, it must have been. I imagine that a short nose fit well on her face, a malleable nose, but very small. A nose that fit the rest of her body, which was diminutive. Large noses exist on small bodies, like the witches who haunted our childhood dreams. But not Selene. Her face was a preamble, an introduction to her thighs. Selene usually wore very short skirts so her thighs were always colorful because they were constantly exposed to the sun and, just below her knees, there was a filigree of scarification that, nowadays, would be the basis for a unique tattoo. She had been burned by sulfuric acid thrown on her in a São Paulo street skirmish in 1968. Selene referred to them when she told the story of that ugly incident. She pointed them out with the verve of a practiced storyteller and the grace of a ballerina. The miniskirt was meant to divert our attention from her scars. Her narrative grace killed two birds with one stone. While Selene spoke of her bravery, her thighs caught the eyes of her audience which was mostly male. We venerated her.

I had never met Selene, until that night. Luiz do Carmo introduced her to me as the “Leader of the Union of Brazilian Secondary Students.” If he had said “This is the recording artist, Ella Fitzgerald” it would have had the same impact.

I will learn later that, even in hiding, she does not use a code name. She is simply Selene. That is how she introduces herself and what I call her from that moment on. She asks if I have a cigarette. I put my pack of Continentals on the table. I observe the deftness with which she extracts and lights one and the suction of her first drag. I want to tell her to keep the pack. But I am ashamed and lower my head. Selene smokes, nods her thanks and gets down to business. “Comrade, we are having serious difficulties surviving. We need a place to crash, money, food, everything.”

“I understand,” I say and feel ashamed to gripe about the hellhole where I live. I have a little attic room, they have nothing. I also have a shitty, unbearable job where I feel like an alien, but it keeps me fed and dry.

Selene continues, “But what stands in the way of victorious socialism, comrade?”

“Speak softly, companion,” Célio whispers through clenched teeth, behind us. Selene regards him, seems about to put him in his place, thinks better of it and turns back to me, voice lowered, “What are our difficulties compared to those of the Viet Cong?” As a petty bourgeois wage earner, I am instantly conquered by her passionate preaching of the revolutionary gospel. I ask only, “What can I do?” Selene looks at me and answers quickly, “Buy me a bowl of soup.” I order and pay for one. “And another beer for us.” When the waiter approaches, Célio asks if he can have a bowl of soup instead. “Of course,” I say, thinking, there goes Saturday at the movies. The soup arrives thick with meat and noodles, Selene claps her hands. The waiter smiles at the hungry little girl. She smiles back. Then, as her spoon returns to the bowl at ever shorter intervals, she declares, eyes sparkling, “There is no revolution without soup.”

We all agree. Célio grunts his affirmation, hand and jaw occupied by vital business. The soup is so hot it scalds his tongue and the roof of his mouth and he cries out. The beer-drinkers at the next table observe this display of human nature with interest. Célio and Selene reveal what revolutionary ardor looks like when it is momentarily abandoned for animal concerns. When Célio finishes, he lifts his smiling face, green eyes wide, and tells me, “That was great!” In his plate there is no trace of noodles or fat, no crumb of the bread that came with the soup. He sucks his teeth. His fingers still grip the spoon inside the bowl. I tremble with foreboding, expecting him to ask for another bowl in exchange for the cigarettes he will bum from me tomorrow. But Célio is disciplined and only repeats, “That was good.” I do not ask, as I was taught, if he “would care for another bowl?” I am conquered but not yet crazy. Selene continues to speak, as she nibbles her soup-sopped bread, “We must eat, comrade. We have to be strong to face the enemy.” We say nothing, because of the spectacle and out of respect for her leadership. When she finishes, she asks for an espresso. “Me too,” Célio says. A faithful follower, he accompanies her request for a cigarette.

“May I?”

“Of course. The cigarettes are ours.” Both of them smoke. But what a difference. Célio inhales and swallows the smoke in silence. Selene is loquacious, eloquent, and emotional between puffs.

Incredible, what we remember in 2021 about 1970. Selene was just 18 and spoke sagely about national politics, Marxist theory and bibliography. How could she be so precocious? How could she be so convincing, even to older militants like me? Yes, I was an experienced elder of 20 by then. Now it seems to me that we were all precocious. Our duties and promises were larger than we were. We wanted to vanquish the Brazilian armed forces, without arms. As socialist militants, we represented only a fraction of the nation’s youth. And, since we were alienated, far from the beaten path, we had to grow up fast, despite our youth and inexperience. We were destined, all of us, for a “high speed” maturity, impelled by the force of the dictatorship, which shook us like a series of seismic tremors. Selene was a motivator, capable of reigniting our passion for the struggle, when necessary, with an astute appraisal of what was at stake. She emboldened us. It pains me to admit it, but we had little time or aptitude for reflection. Here is why.

After I wrote “here is why,” I was immobilized for more than an hour. The searchlights of contradiction cross and recross this page. Their stark white glare is a decomposition of the luminous beams of a prism. The truth is, we experienced a phenomenon to which we thought only religious fanatics, simple country folks following leaders they beatify, were susceptible. The story of the fervent disciples of Anthony the Counselor and his New Jerusalem at Canudos lingered. As young, would-be intellectuals, we belittled them as superstitious people in a barbaric and backward part of the country. Yet we clung to a similar dream. Just like the counselor’s followers, we were carried away in a floodtide of feverish actions, meetings, and words. Far from the rustic confines of Canudos, we were going to transform this dream into the greatest accomplishment of our lives. Starting here in Recife, we would, one day, subvert the world. The difference was that, for the Counselor’s followers, the future was unearthly and had little connection to the daily drudgery of their lives. Whereas for us, the future had been present in some part of the planet since the Bolsheviks overthrew the Tsar and was currently sustained by Mao, the Tet offensive and the heroic struggles of the Viet Cong. This was our dream’s great advantage. We read about other struggles in other lands. We had friends who had studied in Cuba. Our fixation, like that of the unlettered hicks in the Brazilian outback, was faith-based. We were enthralled. These were the primary colors of the light rays that traveled through the prism and illuminated our beliefs. But there were other colors and tones.

Wreathed in and protected by this light, Selene was spellbinding. Strangely, she did not possess a beauty that was captured in 3×4-inch snapshots. On the contrary, she looked like a little girl with freckles, you could almost swear she was covered with them. Other remembered physical characteristics did not fit her either. Not long ago, I asked someone who claimed to know her well, “what color were Selene’s eyes?” No one knew for certain though common consensus deemed them blue. They were wrong, betrayed by her fair skin and light brown hair. Her profile remains uncertain, detained by uncertain memories which require that she stand still long enough for the mind’s eye to focus and recall. Selene’s enchantment was enhanced by her constant motion. Because of our apparent inability to pay attention to her clothes, her shoes, her makeup, what remains is her face and thighs. As I am not a fashion maven, I can only attest to the fact that she wore clothes. I remember there was something greenish about her favorite miniskirt. Resolute investigators would determine her 1970s apparel by examining her social class and revolutionary predilections. But, like pasting clothes on a paper doll, this is an artificial approach. Let us stay focused on Selene’s face and thighs as a step in the right direction. I refuse to be fettered by false modesty and fear of scandal. Selene was her thighs. The hell with my concern that some militant from those years, or Selene herself, would say, “But this is macho reductionism, comrade! Simplistic, self-serving and outrageous!”

The blatant truth is shamelessly sexist. Selene’s glorious thighs were a diversion because her shanks, from the knee down, bore a multitude of scars. These were war wounds from the battle of Maria Antônia. Like Cervantes losing his hand in Lepanto, they reflected a brave new world where young women put themselves at risk to keep the socialist struggle alive. Her thighs were forbidden fruit for us as it was taboo to date a woman on the directorate. “How undisciplined! More like the spirit of a vulgar pig, a petty bourgeois, a coward” was a mild critique for the offense of lust. We worshipped her thighs even though we knew they were hors du concours. What a hellish contradiction! To agitate for freedom is not to be free. We might die in battle or be imprisoned and tortured at any moment. But the libertine camp was closed to us, a dour reality of which we needed to be reminded when we found ourselves dazzled by a glimpse of our director’s ravishing coxas. We did not ogle them. We never uttered a word about them because we never let our craziness escape our addled ids. We made mental note that they were gorgeous and left it at that. Higher duties awaited us, ones we aspired to and accepted with no irony or cynicism. If we erred, even momentarily, Selene, a cigarette dangling from her lips and arms akimbo, would put us back on track. It was okay to declare yourself subversive. When Célio warned her, “Be careful what you say,” she gave him a scornful glance before confessing,

“I get carried away by the force of argument.”

“I know, but we can speak more softly about these things.”

“Did the companion ask for the bill?”

“The companion” was me. I paid for beer and soup and cigarettes and the group proceeded to May 13th Park where we wandered around, talking. She felt freer among the trees and the amorous couples.

“And the work here, how is it going? No, let’s not talk about difficulties. The struggle is hard everywhere. We must call on the progressive sectors. Organize them.”

It is not just her words. She was a living witness to clandestine struggle, the most eloquent person we know. Now, years later, I am still amazed by the greatness of Selene’s deeds and by her discretion and modesty, much of which was difficult to discern in those awful years. After he was granted amnesty and returned to Brazil, Gregório Bezerra said little about it, I remember. But Gregório was not much of a talker. He was a rock of conviction, made of sterner stuff, like a Viet Cong leader who kept his mouth closed even when death was the consequence. Or Patrice Lumumba, who spat out the paper stuffed in his mouth. But eloquence can also be a proof of passionate struggle. There are those whose words elucidate and transmit their militancy. Selene was one.

In May 13th Park, we follow our queen the better to absorb her strident glamor. She is our latter-day Joan of Arc. When she throws her head back, raises her arms and shouts, “I am subversive! I want to turn this world upside down!” it is visceral. She speaks for us, expressing nascent truths we intuit but cannot voice. “Speak, woman! Tell me what you want from me. You who look like a girl but are no longer a child, speak! I am here to serve the cause. Tell me what to do.”

In Selene I saw, for the first time, a non-musical manifestation of what I would cheer as an audience member at performances of the first generation of singer-composers and interpreters of Brazilian popular music. Listening to Luiz Gonzaga sing “Asa Branca” live at an auditorium near the beach prepared me for my evening with Selene and her companions in downtown Recife. Both Gonzaga and Selene had public personalities. Each spoke to the limitless possibilities of the individuals in their audience which, in Gonzaga’s case, was national. Since Party discipline forbade licentious behavior, Selene seduced us in the name of socialism. As we left the park she informed me, “Comrade Célio has nowhere to sleep.”

“I know,” I say, nodding at the three militant musketeers, Célio, Selene and Luiz do Carmo, standing before me. They return my acknowledgement. I am their savior of choice. I stutter in response, “Look, there—there is only one bed in my room.” Silence. Their eyes still fixed on mine. “And—and it is hot—hot as hell. We sweat buckets.”

Selene does not budge. “It beats sleeping in the street. This companion is clandestine and will be jailed if he’s caught.”

“I know. But how can he sleep there if I only pay for one space?”

I did not understand yet that, in the underground movement, you dribbled and feinted your way around difficulties. The question of whether something was “legal” or “illegal” was a “bourgeois problem,” resolved by any means necessary. That was revolutionary ethics in a nutshell. We preferred the term “expropriation” to “robbery” or “theft.” And if the theft were personal? No matter. Under revolutionary circumstances, theft was unappealable. Militants were pardoned in advance. They required tools for clandestine existence: books, a car, identity papers, clothes, sustenance. All “third person” possessions belonging to people outside the movement were up for grabs. The survival of the militant was paramount. And there I was, claiming only one person could sleep in my little sauna because I had only paid for one space.

“Companheiro, there is no cause for concern.” Selene speaks to me dialectically but tenderly from her wealth of experience as a daughter of the people and a fearless combatant. “Célio will climb the stairs in step with you, like a soldier. If the landlady asks, he is your friend, spending just one night with you. More than likely he will be gone long before she awakes. Does that ease your mind?”

“Okay,” is all I can say.

Syndicated by permission of International Publishers.

Urariano Mota

Never-Ending Youth

translated by Peter Lownds

ISBN: 9780717800063

Order a copy here.

Comments