In the summer of 1981, Canada’s economy was in a recession, which by mid-1982 had deepened into one of the worst in the post-WW2 era. Unemployment reached 10.8%, and the city of Hamilton, Ontario—at that time the heaviest concentration of basic industry and manufacturing in Canada—was particularly hard hit. There were several thousand workers on layoff and hundreds whose jobs had disappeared altogether from permanent plant closures.

In order to develop some fightback, the Communist Party had a Canada-wide policy promoting the organization of unemployed workers. The Hamilton and District Labour Council (HDLC) had a left-center executive which included two members of the Communist Party and Harry Greenwood from the Steelworkers as president. A number of experienced union activists were unemployed at the time and available for assignment.

You might say the ducks were all in a row.

The mainstream labor movement campaigned for government funding for workers’ help centers, retraining, and extension of unemployment benefits. This was all well and good, but it still left the volunteers at these help centers under the scrutiny of the government, so it was risky to get too political when the government could pull the funds.

The HDLC executive tackled this problem and decided to go in two directions. They would accept the government funding in order to establish a help center, but they would also support an independent organizing drive to establish an activist union of the unemployed. The left and center on the HDLC executive had made a pretty good compromise that benefited all, and there was no opposition when it was presented to the delegates.

The groundwork had been laid for the Hamilton Unemployed Union (HUU)

Prior to this development, in late 1981 and into 1982, there was a small group of workers called the Jobs Coalition, which was led by a young Steelworker named Mike Groom. Their main focus had been to picket a temp worker company called the “Jobs Mart” (also known as the Slave Mart). The coalition was very effective, and the Jobs Mart, which took a percentage of temp workers’ pay, finally had to close its operations in Hamilton. When HUU was in its planning stages preparing for operations, the coalition agreed to bring in their supporters.

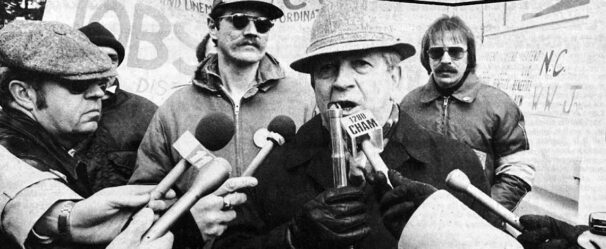

The HDLC executive assigned one of its members, Sam Hammond, to work with Terry Fraser, a seasoned veteran of many struggles. (Hammond and Fraser are the authors of this article.) Fraser was a member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 105 and had initiated and led many campaigns and a groundbreaking strike that had made Local 105 the frontrunner in the building trades.

Steve Jefferies, HDLC delegate from United Electrical Workers (UE), was assigned to work on setting up the help center. He recruited Kerry Wilson, another young activist on layoff from the giant steel company Stelco. Although they both belonged to and supported HUU, their main focus was on the center.

Other notable activists were Joanne Santucci, who is still active as Executive Director of Hamilton Food Share; Terry Tew, a laid-off Teamster from Freightways Transport; and Mike Skinner, a laid-off Steelworker from National Steel Car. Skinner eventually became a staff rep for the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), and Wilson became the president of the Bricklayers and Allied Craft Union of Canada (BACU). Following a merger between UE and the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW), Jefferies became president of CAW Local 528.

In the late summer of 1982, an ad-hoc organizing committee for HUU existed, and there was a general agreement to have proper elections early in 1983. The main pivot person was Fraser, with Hammond as the link to the HDLC executive. The help center established a storefront operation on Main Street near the city center, and HUU opened its storefront headquarters on Barton Street East in the more industrialized area.

The Hamilton Unemployed Union was a stand-alone organization—it never received direct funding from the HDLC, raising its money instead from direct donations by local unions and through fundraising events.

The HUU agenda developed through the needs of workers at that time, and there were usually many campaigns going on at the same time. Hamilton Mayor Bob Morrow (“Mayor Bob”) was a Tory (Conservative Party), but very sympathetic; he had an open door to the HUU and was very helpful behind the scenes in giving advice. Another ally was Sister Helen, a Catholic nun assigned by the Hamilton Diocese to work on housing and social justice issues.

Right from its inception, the HUU made housing a priority. At first, it was an advocate in the fight against evictions and this soon developed into a campaign for low-cost, affordable housing. The most successful eviction struggle was at a rundown property at the corner of Main and Sherman in Hamilton where about 80 tenants were being evicted. The building was scheduled for demolition, so the evictions were for all tenants.

Working with tenants, HUU was able to negotiate reimbursement of the relocation costs, the first and last rental fees, disconnection and reconnection fees, as well as moving expenses. There were many more eviction struggles, ranging from legal advice to physical presence.

Federal and provincial funds were available in the 1970s and 80s for low-cost, non-profit housing, but they could not be accessed by a municipality without the existence of a municipal non-profit housing corporation. Amazingly, due to the political clout of developers and private housing interests, the City of Hamilton failed to take advantage of these funds.

The HUU campaigned publicly and lobbied intensely until Hamilton City Council agreed to form a non-profit housing corporation to access the available federal and provincial funds. The first non-profit units were built on Upper Paradise Road, and these townhouses are still occupied today.

Another successful campaign was for half-price bus fares for unemployed workers, which was expanded to include half-price fares for seniors.

These campaigns took up a lot of time, and they also required financing. The cost of transportation, rental, and utility costs for the storefront on Barton Street East and small amenities like food for campaigners had to be raised, and this was a constant fundraising drive.

The support of the labor movement was vital, and the endorsement of HDLC was key to getting donations from their affiliates. The Teamsters Union, which had the largest hall, donated their facility at Parkdale and Rennie Streets for a fundraiser. The HUU ran a hard-times dance and social for a “buck.” (“A buck to get in, a buck a beer, and a buck for food.”) The 800-person hall was packed to capacity, and the event raised a lot of money. HUU received generous support from many local unions, but the Teamsters, United Steelworkers (USWA) Local 1005, and the United Electrical Workers deserve special mention.

In the summer of 1983, the HUU held an unemployed picnic at Confederation Park in Hamilton. The city had given private concessions control of all food in the park, so it was not possible to organize food through donations. This meant the picnic was held under great difficulty, so in 1984, the HUU was forced to look for other accommodations. It chose Prudhommes Landing on the shores of Lake Ontario between Grimsby and St. Catharines.

The transportation problem was solved when Hamilton City Council was persuaded to donate the cost of shuttle buses if they were rented from the Hamilton Street Railway. The significant rental fees for the park were raised, and local businesses donated abundant food—mostly hot dogs, corn on the cob, and soft drinks. There was so much food that organizers begged the thousand people in attendance to take some home. Gord Wilson, then vice president of the Ontario Federation of Labour, addressed the crowd. The picnic was a great success, but it marked the slow decline of the Hamilton Unemployed Union as the economy recovered slightly and activists went back to work.

Why is this brief history important today?

In this time of looming economic crisis, when the global imperialist system with its rivalries and built-in threats of economic, environmental, and nuclear disaster threatens the existence of our species, it is important for the working class to organize and to resist. Resistance develops from millions of small engagements.

There have been generations of working-class engagements with capital, ranging from national, anti-colonial liberation movements to socialist revolutions. The experience of the HUU is a tiny part of this, but nevertheless, it proves that workers—unemployed, precariously employed, or fully employed—can be organized if there is a will to do so. With proper resources and enough commitment, the labor and social justice movements can organize all strata of the working class.

There is no other option. This is a necessity.

Comments