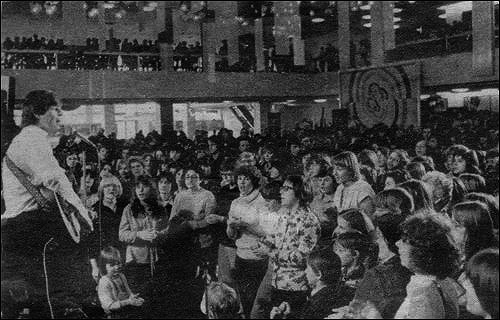

BERLIN—A crowd gathered at the Babylon Theater here Saturday for an annual memorial for Dean Reed, the American “rebel,” rock star, and filmmaker who famously defected to “East Germany” (the German Democratic Republic, or GDR) in 1972. Those in attendance were among Reed’s most ardent fans, of whom he had many thousands in the GDR when he died in 1986.

People who were around 20 years-old when the Berlin Wall fell—those who lived in and were educated in the socialist GDR—have spent the more than quarter-century since the demise of that country living under capitalism in a different Germany. Being old enough to remember what life was like in the GDR, they are perfectly situated to make comparisons of the two different social systems. At the Reed memorial, I had the opportunity to speak with a number of them.

These former GDR citizens, referred to these days as “Ossies,” a short for the German word “ost,” meaning east, said some things that were not surprising, but also others that were completely unexpected.

“I wasn’t political at all”

Heike Zastrow, who was exactly 20 when the Wall crumbled in 1989, was slicing cake to be served during intermission when I spoke with her.

“I wasn’t political at all and I didn’t like the steady talk of politics coming from the leaders,” she said. “I also hated that I couldn’t travel, I couldn’t go where I wanted to go.” Once the border around West Berlin, which was in the middle of the GDR, was closed in the early 1960s, most GDR citizens under retirement age could not travel freely to the West. Permission was granted for various reasons, but it was not the rule.

“But I have to say,” Zastrow said, “that I had a very good life in the GDR and that I had a very good education there.” I asked her to elaborate.

“We never worried about not having a place to live or a job, or about being evicted. There were no worries or fears about our livelihoods and there was so much in the way of culture and recreation that was available most of the time at little or no cost.”

She said that “attempts were always made not only that you had a job but that it was the best job you could do and whenever possible a job you really liked.”

Zastrow explained that she disliked the technical aspects of her schooling, despite the fact that they were providing her with skills that were quite useable. “I love animals,” she said, “and really wanted to have a career working with them.” She described how “there were needs for everything in the GDR, for people who could do all kinds of things and they worked to get me a job that I loved, a job on a large agricultural dairy collective where I had such good times working with more than 300 cows!”

Sadly, she said, the economy was restructured when the GDR was absorbed into West Germany and many industrial and agricultural concerns in the GDR were dismantled. She was able to find a job as a quality control inspector in now-capitalist Germany at a brown coal power plant. “While I would much rather work with animals the way I did in the GDR,” she said, “I was able to get a good new job because of the solid education and training that I had received in the GDR.”

“I never, ever wanted to get rid of socialism”

Another GDR citizen I interviewed had quite a different story. She came to the GDR as a three-month-old child and has been a German ever since. “I know no other country,” she said.

She also had praise for the free education system in the GDR, saying it had prepared her well for her chosen field of printing and publishing. At an early age, she started and remained at Neues Deutchland, a major GDR newspaper, doing typography and design.

She had complaints, however, about aspects of life in the GDR. One was that she felt the schools, equipped as well as they were to build knowledge and skills, were not adequately equipped to deal with children with special problems.

She had behavioral problems as a child, and in her schools the emphasis, when it came to behavior problems, was on conformity rather than searching for solutions. “I made it through though even though it would have been better if there had been more help from the schools,” she said.

The other complaint she had was that “there was often too much bureaucracy, too much complication of matters that could have been simpler. And I didn’t like many of the functionaries; some of them were incompetent and others were corrupt.”

None of her misgivings, however, seemed to have soured her on the idea of socialism.

“I want to emphasize that while many of us wanted some of these small things to change, I never, ever wanted to get rid of socialism. I wanted some changes but not what eventually happened, no not that.”

She was asked to explain further.

“You see I am not fair complexioned or blond looking like many Germans,” she said. “I know you find a**holes under any system. There were people with racist feelings in the GDR. But expressions of racism were illegal there. You had to hide it if you were a racist. You couldn’t go out and attack someone for their race or color or beliefs.”

She explained further, “In Kreuzberg, [a neighborhood in Berlin that was in the West when the city was divided] my 12-year-old son was harassed and attacked by Nazis, young people expressing and acting on Nazi ideas they get from their parents. He was okay physically, but this does psychological damage to a child. That could never happen in the GDR.”

She said she was at the Reed memorial because she was a great fan of his in the GDR. “He went around the world pushing for rebellion against injustice and for peace. I wanted to be here today to sing a song of struggle from Latin America, a place where Reed spent some years of his life.”

On the elections happening in Germany, like so many Germans she was shy about proclaiming who it is that has her support. She said she wasn’t sure yet how she would vote. “It will be for someone committed to socialism, however, I will tell you that much,” she said. “I dream about a truly democratic socialism,” she said. “I just know it. I just feel it is possible. We had an imperfect socialism but I believe we can do it better next time.”

From capitalism to socialism to capitalism

One of the speakers at the memorial, a man who knew Reed personally, was Victor Grossman, known to People’s World readers as a frequent writer and reporter on European affairs.

Grossman was a young factory worker in Buffalo, N.Y. when he was drafted during the Korean War. He was stationed in Germany, where he learned that as a left activist he was about to be arrested and jailed in a McCarthyite campaign in the military that was running parallel to the hysteria back in the U.S.

The jail term would be five years and the fine $10,000 for having failed to list allegedly subversive organizations to which he had belonged. The story is complicated, but he fled the army base and ended up, like Reed, living in the GDR and has remained in Germany ever since.

Grossman’s experience is quite unique. He lived the first 20 years of his life under capitalism in the U.S., the next 40 under socialism in the GDR, and the last 27 under capitalism in a united Germany.

In this particular interview, we stuck mostly with Grossman’s practical life comparisons between the two systems. “In the Buffalo factories with 1,300 workers,” he said, “We didn’t have washrooms or lockers, and we didn’t have a lunchroom either. We had all those things in the GDR factory and we got a hot meal for lunch which is the main meal of the day in Germany.”

The biggest difference, according to Grossman, was in the area of job security. “In Buffalo, it was out of the blue that Fedders laid 200 of us off. That’s it, we were out of work, livelihood gone. In the GDR, you never, ever had to be afraid that you would be kicked out onto the street. Even if a job was phased out, the system was fully in gear to get you the next job without you ever suffering loss of pay or pension benefits or anything else. You can’t imagine how good it is to be free of that economic anxiety,” he said.

For some brief but shining years, the GDR was achieving more and more of the aims of socialism. The powers-that-be today are afraid of this. They don’t want people to know that there was an actual world in which fear of joblessness was gone, poverty was eliminated, women had equality, racism was illegal, and no child went hungry.

In Grossman’s U.S. school days, tuition was a lot lower than it is now. Nevertheless, he said that schools, including higher education in the GDR were not only top-notch, but free. “You didn’t have to work a job to help pay the bills, you could devote full time to your studies.”

Grossman did just that, having graduated from Karl Marx Stadt University as a trained journalist. He went on from there to teach and write several books in the GDR.

Grossman’s biggest accolades were reserved for what the GDR did regarding housing and elimination of poverty. “Everyone had a home,” he said. “Rents were very low and you could never be evicted. It was unheard of, and the GDR was really the first place to ever completely eradicate poverty.”

Socialism had its problems, too

None of this means there were no problems, Grossman said, and he had some of the sharpest criticisms voiced in the interviews on Saturday night.

“They never were able to take well any public criticism of the leadership,” he said. “You could criticize your boss on the job, the way things were set up there, you could criticize delays or bureaucratic glitches. Of course in America, you can criticize the political leaders but watch out if you criticize your boss or the people who run your company.”

He admitted too that there was the ever-present Stasi, the state security agency thought of in the West as all-pervasive and fearsome. “In my building, there were two Stasi agents,” Grossman said. “Everybody knew who they were, but nobody really gave a damn. If you didn’t complain about Honecker (then the GDR’s head of state), you never heard from them or saw them. They were not a part of the life of the majority of the people, but we always knew they were there.”

Grossman had nothing kind to say about the official newspapers, “They were bad,” he said, “dull and uninteresting—put you to sleep, and since they rarely discussed real problems, people didn’t believe them even when they were often telling the truth.”

And, of course, Grossman said, “There was corruption as there is in any system.” He said in the last months of the GDR he had written to and gone to see the head of the Berlin organization of the ruling party (Socialist Unity Party). He urged the party to initiate a campaign to explain to people why the stepped-up capitalist propaganda was problematic and how important it was to find good young speakers to talk about the gains of socialism that, as Grossman put it, “had to be preserved.”

Grossman said his concerns that the party leadership was not fighting hard enough to address the crisis were brushed off, and that when the Wall came down, “The Berlin party leader himself went over to the other side. He was a traitor.”

Yet today, more than a quarter-century after the demise of the GDR, there is a persistent campaign here and all over the West against that country. Every official tour of Berlin is sure to include some anti-GDR points of information.

“Why do you think that is?” I asked Grossman. Why continue to vilify a country and a government that disappeared decades ago?

“It’s simple,” he said. “For some brief but shining years, the GDR was achieving more and more of the aims of socialism. It had eradicated poverty. Socialism was the only system ever to have done that anywhere. The powers-that-be are afraid of this. They don’t want new people and young people to see this. They don’t want people to know that there was an actual world in which fear of joblessness was gone, poverty was eliminated, women had equality, racism was illegal, and no child went hungry. And most of all they fear the return of a society that drew a line, a line that Krupp and Siemens and Deutsche Bank could not cross, a line where their power was stopped.”