I speculated out loud to some moderate Milwaukee voters of my acquaintance (at least more moderate than I am) that Paul Ryan might simply resign. I got that “You are crazed with wishful thinking” look and was roundly mocked for my lack of political acumen.

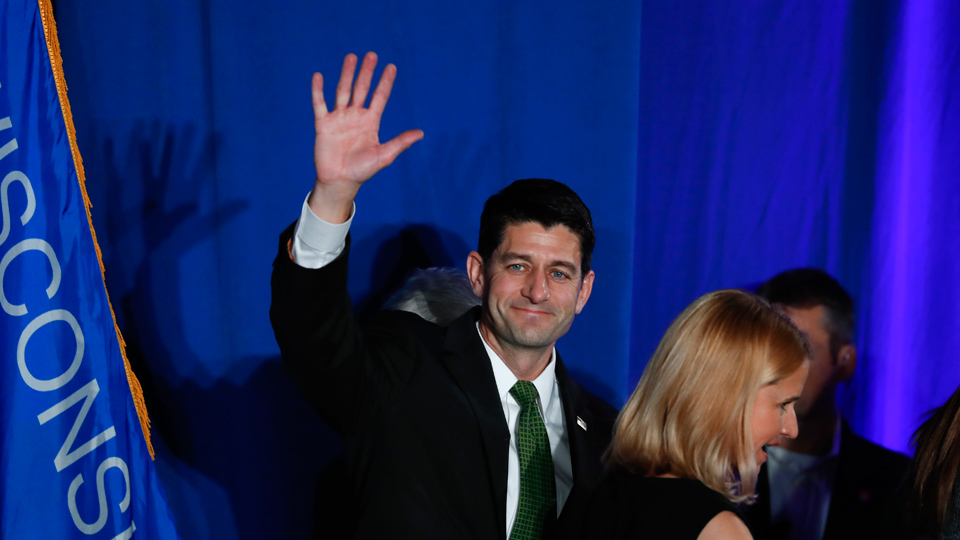

Yet sure enough, on April 11, he did just that. And going further than many of his Republican colleagues expected, he announced that at term’s end he was not only resigning the Speaker of the House position he took so reluctantly in 2015, but also not running again as representative for Wisconsin’s 1st District, where he has served since 1999.

In Wisconsin, the conclusion was simple: He was running in fear of the Democratic wave—even though the district had been gerrymandered Republican, even though he had far more money, and even though he was leading in the polls. But people in Wisconsin at least had more undercurrents for their beliefs than D.C. Republicans, who did not expect the double whammy exit, despite what they say now. Resigning as Speaker—second in line for the presidency—and also from Congress?

Yet the logic behind his decision was self-evident, and it goes beyond getting far way from Trump.

To begin with, there is a good chance the speakership will revert to the Democrats, who look poised to regain power; and in any event, Ryan has performed so poorly as speaker, unable to control his members who are either for or against the president, that he would have been forced aside. He just beat his caucus to the punch. (Many are already pushing for gun survivor Steve Scalise.)

There’s also a D.C. echo of what has upset many Wisconsinites. Elevated because he was the budget hatchet man, Ryan dropped the hatchet again and again rather than confront his own party—and the state’s conservative GOP took notice. As did his former close allies. “This Congress and this administration likely will go down as one of the most fiscally irresponsible we’ve had,” said departing Republican Sen. Bob Corker.

Moreover, Ryan has traded on his Catholic reputation in a state that credits religious beliefs. His backing away from commenting on Trump’s proclivities and tweets and his saying he really hasn’t paid attention to the Stormy Daniels imbroglio let home voters see something less than the moral center he once touted. He simply doesn’t seem a moral figure in action, either at home or in D.C.

Only that big tax cut program, which has as many haters as admirers, stands in his mind as an accomplishment. His one achievement is something of a farce, as historians like to point out that the last effective tax bill any House Speaker could take credit for was the one 32 years ago from Democrat Tip O’Neill.

His image is predicated largely on his baby blues and young buff looks, hard to maintain at age 48. But it also came about because in 2010 the president had to deal with Republicans on that year’s budget and elevated Ryan (thanks, Obama!) for being one of the few Republicans willing to talk issues. OK, even Obama can be wrong.

That, and a clumsy stint as Mitt Romney’s running mate in 2012, explained his prominence—except in Wisconsin, where he was always treated as a favorite son. Gov. Scott Walker tried to turn himself into that sort of national figure, but Ryan was the only real favored son—a position he can no longer trade upon.

In terms of his economic platform, slashing Medicare and a number of programs he called entitlements, it was unpopular with many Republicans. Even Romney avoided talking about Ryan’s economic insanity. Today, his GOP subordinates are split between those who thought the recent tax bill went too far and those who thought it didn’t go far enough.

Much of the blame is assigned to Ryan’s continuing failure to wrangle the herd he inherited from John Boehner. (Boehner at least had a sense of humor about it, judging from The New Yorker cartoon in his Speaker office.) In contrast, a grim face has been Ryan’s favorite look. His inability to take a convincing position in this turmoil became another reason to leave.

In Wisconsin, he is being challenged as never before by two Democratic opponents—one of whom, Randy Bryce, has become a national figure and raised more than $4.5 million, the other Janesville school figure Cathy Myers, who has just launched her first TV ads.

Wisconsin Democrats have no doubt that Ryan is quitting before being run out by the Democratic enthusiasm led in his district by “Iron Stache” Bryce, whose detailed platform is far more intellectually savvy than many expected from his workingman commercials.

The favoritism toward Ryan’s opponents exists despite his continued edge in polling (from 6 percent to 15 percent, depending on whose poll is being counted), his vast superiority in money (three times his nearest opponent), and from favorable gerrymandering that by itself has almost guaranteed the 1st District stays Republican.

But all that is clearly backfiring. In three of the county slices included in his district, Ryan has been losing. Only Walworth and Waukesha voters have stood on the bridge to turn back the tide, and now many of them are taking to boats.

Champagne is being bought and uncorked all over the state by the Bryce campaign, the Myers campaign, the Working Families Party, Forward Kenosha, and other progressive groups, some of whom have already announced their support of Bryce, as has the DCCC. Even Democratic candidates in historically red districts have jumped to proclaim the time is ripe. (When Ryan told the D.C. press his departure “would have no effect on any race,” he was flat wrong in Wisconsin.)

“It’s the clearest indication yet that Wisconsin voters aren’t buying his plan to cut taxes for the rich at the expense of important programs like Social Security and Medicare,” said one, Julie Henszey, facing a huge hurdle in replacing rabid conservative Leah Vukmir in state senate District 5 as Vukmir tries to knock off both a Republican opponent and U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin.

With clearly enough tasks in front of her, Henszey is using Ryan’s departure as a clarion call, and she is hardly alone among state Democrats.

In D.C., the Republicans are more in a state of shock. Some are eager to accept Ryan’s main reason that he’s leaving: He wants more time to stay home with his wife and family.

That produces pure derision from working mothers in his district. Not that Ryan hasn’t been projecting an image as faithful weekend father, but his three children are all now teenagers. They hardly need daddy around to tell them what to do or how to protest. “If Ryan really cared,” said one mother to me; “he should have been home more when they were going to elementary school—that’s when he would have learned about real fatherhood.”

Even D.C. Republicans aren’t buying another claim from Ryan—the one about his work being mostly done so he can leave with no regrets. He is actually ending a run as one of the most ineffectual Speakers of the House on record, leaving behind ship-sinking debt that deliberately contradicts his economic platform.

His statements about the nobility of his presence have grown more ridiculous to voters in his own district. Land holders in the future home of Foxconn, Mt. Pleasant, complained to him about the state’s use of eminent domain to seize their property because they knew he had twice backed federal legislation to curb the state practice. When this time he said he couldn’t help them, voters took it as another sign of his hypocrisy—and cowardice to stand up to his own party.

However, Ryan can continue to influence his party because of money—some $14 million in combined campaign and PAC money on-hand, having already raised $40 million for the Republican National Committee. His increased fundraising activities in recent works misled many Republicans that he was ready to run again.

Now they are clamoring to learn what he will do with those funds he is sitting on. More help for the RNC? Or more focus on threatened Wisconsin Republicans? These include U.S. Rep. Sean Duffy, fighting off many effective Democratic gnats in District 7, and Rep. Glenn Grothman, facing a strong charge from former Sen. Herb Kohl’s nephew, Dan Kohl, in District 6.

And who will run to replace him? Ryan has already indicated he will not support the racist right-winger announced against him for the primary, Paul Nehlen, but the district is still gerrymandered in Republican favor. So there is speculation that former White House chief of staff and good Ryan friend Reince Priebus would step in. Or maybe Assembly majority leader Robin Vos. Or other state names that have a local GOP following and some concern about running in their districts in November—state Sen. David Craig and state Reps. Tyler August and Amy Loudenbeck.

Wisconsin is pretty well convinced that Ryan quit over fear of Democrats—and there is much truth there. No politician gives up power without a push.

Whether the hostility toward Ryan transfers to any GOP substitute, or if it will diminish now that Ryan is gone—thereby may hang the future of Wisconsin politics.

Comments