What if prisons moved past archaic notions of “punishment” and shifted instead towards rehabilitation models? Stateville Calling explores the possibility of restoring incarcerated people’s lives, highlighting the personal narratives of elderly prisoners. Directed by Ben Kolak and produced by Yana Kunichoff, the hour-long documentary follows the current battle to pass legislation reinstating parole in Illinois, which the state hasn’t had since 1978.

Bill Ryan is an 84-year-old former social worker from Kentucky. After deciding to retire from his field of work, Ryan began to visit prisoners who were serving life sentences. He first drove up to the Pontiac Correctional Center in 1993 and met with a man scheduled to be executed. The brief visit greatly impacted Ryan’s view of the criminal justice system and set him on the path to becoming a prisoner rights activist.

Stateville Calling delves into the friendships that Ryan has developed with incarcerated men and women over the span of several decades. As part of his ongoing efforts campaigning for reinstating parole, he frequents an all-women’s prison in downstate Illinois and helps share the personal stories of prisoners with local legislators. There is an urgent need for advocates, like Ryan, in the criminal justice system because of rampant censorship.

Parole is the practice of releasing inmates before the completion of their maximum, court-appointed sentence. These released individuals—or parolees—would then serve the remainder of their sentence under a period of supervised and conditional release, during which failure to follow certain rules may lead to the revocation of parole.

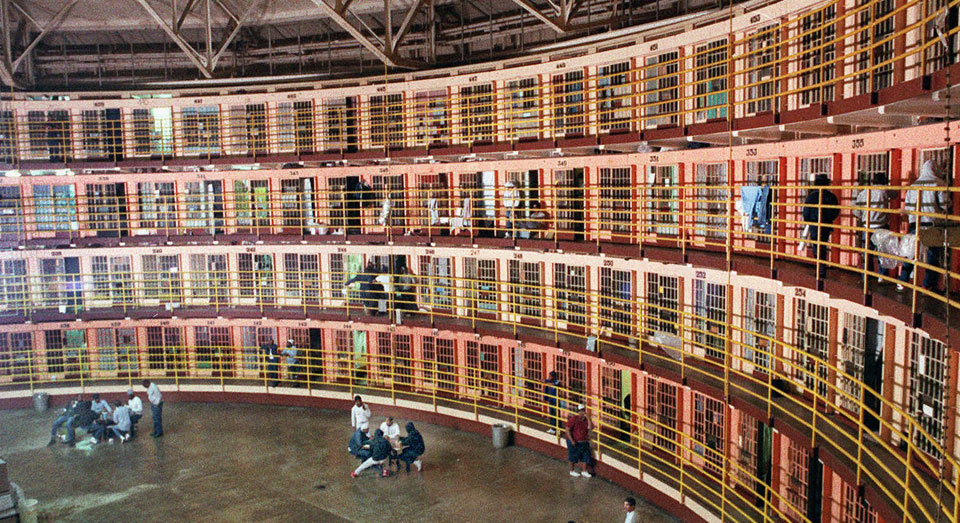

Many of the incarcerated people featured in Stateville Calling are decades removed from their original conviction; a number of them are now either physically disabled or suffering from chronic illnesses. The elderly population in jails across the country is now growing at a higher rate than any other group of prisoners. In Illinois, a state that suffers from massive budget cuts, this has placed a financial burden on a prison system already struggling to provide basic resources for incarcerated people.

According to studies, nearly 20% of the inmates in the Illinois Department of Corrections are considered elderly. This figure has more than doubled since 2010, and is expected to climb past 30% by 2030. For years, criminal justice experts have insisted that releasing elderly prison inmates would not only save Illinois money—but do so without risk of endangering the public.

One of the major barriers that prison advocates currently face is that “tough-on-crime” legislation from the late 1980s and early ’90s has made it nearly impossible for offenders to earn “good time” credit. In the documentary, Uptown People’s Law Center (UPLC) Executive Director, and attorney, Alan Mills, points out that Illinois’ current system doesn’t incentivize good behavior on the part of prisoners. Mills poses a hypothetical where there is a “good” vs. “bad” inmate. Under the current Illinois guidelines, the “model inmate” would not be awarded for following the rules.

Illinois currently has no system of parole for adults whose conviction occurred after 1978. Community organizers are particularly invested in passing legislation that restores parole for people who are 20 or younger when the crime for which they are charged occurred. This would shift the focus from the “punishment” aspects of prisons back to the rehabilitation model that is commonly used in other developed countries.

Moral standings aside, reinstating parole seems to be the practical trajectory to take from a public policy perspective. Illinois prison systems are some of the most overcrowded in the country, which redirects public resources from other things in order to carry the burden of our overly zealous incarceration rates. Today, Illinois remains one of just 16 states (plus the District of Columbia) without any means for incarcerated people to earn parole.

Stateville Calling begs the question: What if rehabilitation was a human right? What if being in prison meant that you had the opportunity to meaningfully reflect upon your actions and re-enter society a changed person? With resources and state support, the incarcerated people of the Illinois prison systems could have a second shot at redemption. In the meantime, advocates like Ryan and the staff at Uptown People’s Law Center continue to raise awareness of the issue.

Comments