LOS ANGELES—Two sudden, unexpected events bracket Stephen Adly Guirgis’s Between Riverside and Crazy now enjoying its riveting Los Angeles premiere production. One event, a race-based shooting, takes place eight years before we meet this colorful cast of characters. The acts of grace take place in the final scenes. We don’t want to give away too much of the plot, but we couldn’t help thinking of Marvin Gaye’s song “Sexual Healing.”

Almost without exception in my experience, we can count on the excellent judgment of the Fountain Theatre for presenting Really Important Plays that do not Rest In Peace but Rise In Power. Between Riverside and Crazy, which shuttles between quicksilver emotions of pathos, rage, love, memory, irony and revenge, needs to be seen.

Former New York City beat cop and recent widower Walter “Pops” Washington (Montae Russell) inhabits a sprawling, rent-controlled New York City apartment on Riverside Drive. Lonely without his late wife Delores, he has filled his living space with his newly paroled son, Junior (Matthew Hancock), Junior’s spitfire girlfriend Lulu (Marisol Miranda), and a young Puerto Rican houseguest, Oswaldo (Victor Anthony), who’d seemingly otherwise be on the street and has “adopted” Pops as his own.

Pops has an outstanding lawsuit with the city, because the guy who shot him six times eight years ago was a fellow cop. All this time Pops and his legal team have been stubbornly holding out for a bigger settlement, but with the passing of years, the public has largely forgotten the case and a sizable payoff seems less and less in the cards. Now the NYPD, represented by Pops’s former partner on the beat, Det. Audrey O’Connor (Lesley Fera), and her careerist fiancé Lt. Dave Caro (Joshua Bitton), is demanding his signature on a final deal which gives him a few laughably intangible perks (like museum openings and benefit dinners) and an extremely paltry wallet.

If Pops has “justice” on his side (even though he has bent the facts of the case somewhat), the NYPD and the city also have weapons: They can make life rough for Junior, who has not entirely reformed himself, they can sic the landlord on him for violations of his lease and threaten him with eviction, which would be a serious change of life as that apartment would now fetch up to ten times its current rent. On top of which he’s got a neighborhood Church Lady (Liza Fernandez), a Brazilian seer trying to give him a kind of voodoo candomblé communion for his sins. Pops drowns his troubles in booze and pie. In short, he’s a guy living “between Riverside and crazy.”

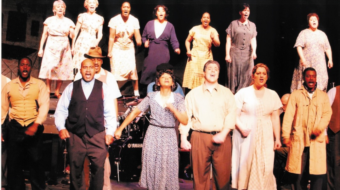

Guillermo Cienfuegos, an always welcome name as director of anything he puts his signature on, puts these seven characters through their paces, sometimes hilarious, sometimes agonizing, in a seamless, breathtaking ensemble. He brings out the sorrow of contemporary urban life, police crimes and corruption, while simultaneously pointing to life-sustaining hope, faith and the people these characters call family. Almost incredibly, everyone in the play ends up in a different place from where they began.

Speaking of which, although he’s not a character in the play, Rudy Giuliani—in his pre-presidential lawyer life—is referenced in one comic scene that still rings true five years after the play was written.

According to an interview with Guirgis in New York’s Newsday, the play was partly inspired by his own childhood. “My father had a very working class existence,” he said. “He worked on his feet, there was no pension. He didn’t really have anything when he died, no money, no nothing. He didn’t have anything to give his children other than his rent-controlled apartment. Me and my sister grew up with all these different people that we never knew who were staying over. A lot of them were family, sometimes they weren’t.”

The playwright’s work includes such titles as Our Lady of 121st Street, Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train, In Arabia We’d All Be Kings, The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, The Little Flower of East Orange, and for his Broadway debut, The Motherfucker with the Hat. A theme of religion in modern life threads through his oeuvre.

“The play explores important issues of race, policing and gentrification—but in the end, it’s all about family, forgiveness and redemption,” says Cienfuegos. Guirgis uses a hip, earthy vernacular in a paroxysm of hyper-realism to clothe his ultimately sublime philosophical approach to life.

The 2015 Pulitzer Prize committee called Between Riverside and Crazy “a nuanced, beautifully written play about a retired police officer faced with eviction that uses dark comedy to confront questions of life and death.”

The role of Pops fits Montae Russell as though it were written for him. He bears his suffering like a lead character in an August Wilson play—and indeed he is a noted Wilsonian, having performed in the entire cycle of his ten plays about African-American life decade-by-decade throughout the 20th century. His suffering has sharpened Pops’s character. What he cannot squeeze out of the city in a final payoff he will secure by any means necessary, in a form of “reparations” for the white man’s mistreatment of him and his family. He also pays back the grace he receives in an entirely unexpected way that will have students of the drama debating and discussing for decades to come.

If Black Lives Matter, then Blue Lives Matter, too, and in this play the two parts of Pops’s consciousness are fused into one. “I think that our white hats have dirt on them, and the black hats are gray, you know?” Guirgis told Kilian Melloy in Edge. “In life sometimes things are just black and white—sometimes—but on stage and in literature, what’s the purpose? What’s interesting is gray. I try to make everybody a little dirty, and a little clean.”

In the world of New York City cops, as Pops, Audrey and Dave all agree, sometimes it’s required to “do the wrong thing to do the right thing.”

The production’s creative team includes scenic designer David Maurer, who takes a modest-sized stage in an under-99-seat house and gives us the illusion of a spacious kitchen, living room, bedroom, foyer and rooftop. Lighting designer Matt Richter, sound designer Christopher Moscatiello, costume designer Christine Cover Ferro and prop master Shen Heckel all do fine work.

Between Riverside and Crazy runs through Jan. 26, with performances on Fri., Sat., and Mon. at 8 p.m, and Sat. and Sun. at 2 p.m. Pay-What-You-Want seating is available every Mon. night in addition to regular seating (subject to availability). The Fountain Theatre is located at 5060 Fountain Ave. (at Normandie) in Los Angeles 90029. Secure, on-site stacked parking is available for $5. Allow extra time for street parking. For reservations and information, call (323) 663-1525 or go to www.FountainTheatre.com.