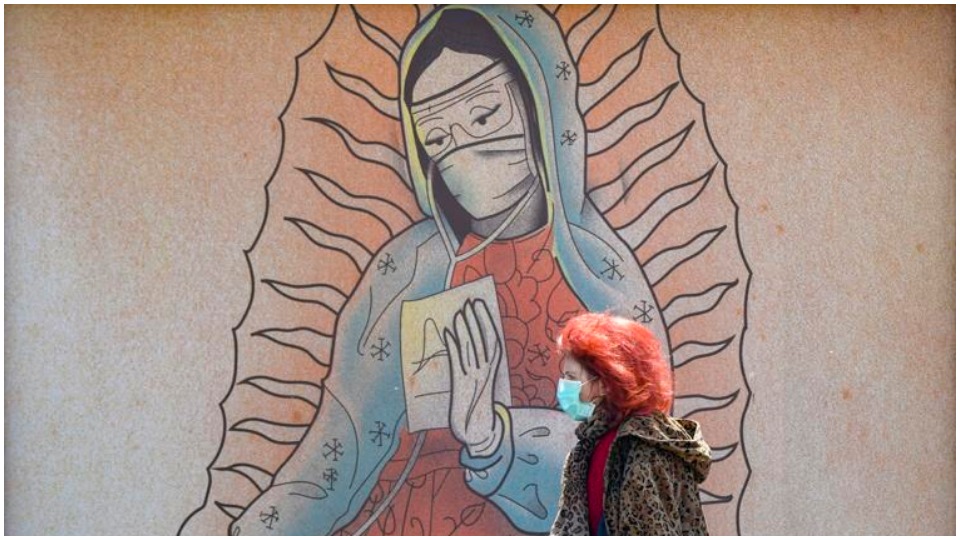

The current coronavirus pandemic, in its scope and potential harm, demands that everyone, including members of religious groups, adhere to what best serves the common good. It might seem to be almost a truism, a given fact, that people everywhere would welcome, without question or dissent, measures to mitigate or slow the spread of a deadly virus.

Yet one need not look far afield to find vehement protests and disregard. Does the opposition to physical distancing in churches and other religious communities lie in religious belief—that is, in creed or theology, in the need for communion—or is an underlying ideology at work opposing the better interests of society as a whole? What part does religion play overall in the disturbing trends seen in the angry anti-shutdown protests? Has religion in general, or just a segment of it, been co-opted and perverted to serve right-wing interests?

Religion thrives on human gathering. Beyond individual beliefs, it is itself a strongly communal experience. Above all else, it is its social aspect that provides a sense of identity and belonging. On the surface, to set limits on the gathering of the faithful runs deeply contrary to what many believe and hold dear and what they have been taught to cherish and protect. Sacred texts encourage and set a tone of obligation concerning the gatherings of the faithful: “Where two are more are gathered I am present in their midst,” and “Forsake not gathering together, as is the practice of some,” read passages of the New Testament. Hebrew scripture also instructs to “Gather the people… that they hear, that they may learn… that they may do all the words of the law.”

The very names by which we refer to places of worship, such as church (biblically, ecclesia) and synagogue hearken to gathering; both words literally mean “call together” or “bring together.” The Jewish tradition mandates a minimum of ten—a minyan—to hold religious services, and in the more Orthodox communities, these had to be adult males. At the same time, although the sacred texts call upon believers to assemble with one another, there are equally strong prohibitions concerning religion for show: “Be careful not to practice your religion to be seen by others.”

Nevertheless, while others practice prudence and rational caution for public health—concerns that are moral and ethical as much as they are medical—many of those who are in positions of religious leadership rush in haste to assemble their congregations as if faith would disappear from the face of the Earth if they did not. Ironically, gathering during a contagious pandemic speaks more to a specific lack of faith and wisdom, or perhaps more to a particular political and economic agenda. Even in the event that physical distancing precautions are required in such gatherings, wisdom is altogether absent in resuming religious gatherings now as cases of COVID-19 and resulting deaths reach all-time highs.

Recent actions around the country have brought to light numerous examples of religious leaders staunchly defying state and municipal mandates on COVID-19. One of the most visible has been Pastor Tony Spell of Life Tabernacle Church in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Even after the death of a congregant due to coronavirus illness, Spell has reportedly continued to demand his divine right to gather the congregation for Sunday worship. Is this obstinacy and resistance merely a narrow, literal-minded approach to sacred texts and practice, or is it the result of confusing right-wing values with religion?

More than having to do with personal belief—such as belief in supernatural protection from harm or illness—the enthusiasm to get things back to business as soon as possible points to the commodification of religion and to forms of it having been turned into an expression of the capitalist ideology of the right-wing state. While not every variety of public religion may be said to have come under the influence of ruling-class domination and ideas, one must still recognize that such influence is pervasive. Religion may be said to have done a poor job of protecting itself from influences that conflate extreme nationalism with faith. To be clear, it is not just religious people who stand in opposition to physical distancing and are part of the rush to re-open business and society, but one must still wonder about the degree to which right-wing values fostered by fundamentalist religious expressions play a role.

Karl Marx famously called religion the opium of the people. He saw that the religious experience of his time provided illusory happiness by directing the focus of the people away from the task of building a better world in the here and now. He saw religion as shifting that gaze to a hope in something beyond, which even the most credulous of people must admit has little impact on life in the present.

In our time religion may no longer fulfill the exact same “opiate” role as it once did, although it does still tend to provide a sense of misplaced solace in a world that continues to exploit and oppress the vast majority while avoiding actual amelioration of conditions. If anything, the burden is now upon religion to address the world’s suffering as part of a positive, progressive, societal effort rather than to bolster systems of oppression or shift attention away from the numerous real and serious issues and threats that demand immediate action by all people. In some circles, this new attention has been called “liberation theology.”

In our times, consumerism has arisen to take the place of the opiate quality once held by religion. Consumerism conditions humanity to believe in the possibility of existential happiness by means of attaining material wealth. It makes promises that it seldom keeps while placating needs minimally and temporarily. In place of religion, we are bombarded with advertising in every medium to the end of finding our true human fulfillment in the power to purchase goods. We are conditioned to desire consumable products in such a way that we have come to believe that avarice is part of our human nature. It is not uncommon to hear the argument that socialism stands to fail because it goes against who we are as humans. The truth is that so-called “human nature” is not something easily identifiable, if it exists at all in that sense. What we mistake for human nature is, in fact, more a behavioral conditioning that has come about through the efforts of the capitalist class. In it, we are alienated from our true human potential.

In keeping with Marxist analysis, the products we consume are commodities, i.e., they have exchange value, and religion in the 21st century has become yet another commodity among many. For religion to be successful it must be marketable; at least this has become the dominant view. Religion as a commodity stands as one of many products we may purchase in order to gain happiness, a happiness that is an illusory freedom while the underlying truth of our captivity continues.

In the world of fundamentalist and evangelical megachurches, there is often little to distinguish them from cleverly designed pyramid schemes: The success of such organizations depends upon convincing their adherents to assemble in person in order to provide a concrete marketplace where spiritual goods are exchanged for monetary investment. A notable modification of this model is seen in televised religion, which now in the pandemic is experiencing a revival through the use of social media platforms such as Facebook and Zoom. But at least as far back as the 1980s, and before then on radio, networks such as Pat Robertson’s CBN have flourished as venues to promote right-wing politics and presumed traditional values along with the prosperity gospel message—the religious blessing of wealth.

The more successful televangelist pastors typically deploy vast exploitable private properties. Such properties exist across America, and when coupled with televangelism they become lucrative investments with numerous opportunities for additional profit through merchandising. Kenneth Copeland, a Texas-based televangelist, has a reported net worth of $760 million. Fundamentalist leaders have a great deal in common with those who side with big business and the financial market. They favor the capitalist system in a way that rivals the sacred. The image of Jesus chasing the merchants and moneylenders away from the temple is not one you would likely encounter in this environment.

For some time, the right wing has been busy befriending evangelical and fundamentalist religion as well as finding allies among conservatives in mainline denominations and Catholic integralists, especially among certain members of the hierarchy and with a particularly vocal ultra-right internet following. Fundamentalist expressions of religion have historically in the U.S. been given license to manipulate their followers to see dominionist ideas around such themes as nation, race, flag, militarism, governance, and even the office of the president, as being part of one’s faithfulness. In what amounts to idolatry, nationalism has become synonymous with having faith.

The idea of divine favor and punishment motivates followers to gather and to invest monetarily in that which will afford them a share of both temporal and eternal happiness. Prosperity has come to mean that one has found divine favor, and the leaders of religion-as-commodity stand to gain a great deal. Poverty, to the contrary, stands as a sign of the curse of sin, as does illness in a newly revived punishment concept of disease and disability. America suffers now at the hands of an unseen virus because its populace has not completely bought into the correct brand of fundamentalist religion, or so they would have us believe.

For fundamentalists, the curtailing of religious gatherings amounts to a threat to the system in which members hold religious conviction concerning their happiness. However, the current situation need not be an indictment against religion on the whole. Expressions of religion exist in which the basis of its teachings lies in liberating all people from the stranglehold of the false belief in acquiring goods and monetary wealth. Religious expressions exist in which spirituality lies not in the selling and market trade of yet another commodity, but in freeing the masses from illusory claims and false hopes of wealth and property. Such progressive religious trends find themselves more and more among the minority with each passing day. They have been “tainted” by their historical association with capitalistic religion.

It also needs to be noted that especially younger people have become so offended by the perversion of religion into a pillar of support for personal and societal oppression that they have left the houses of worship in their rear-view mirror. The numbers of the “nones,” those professing affiliation to no religion at all, or who may be instinctive humanists at core, continue to grow exponentially.

I recently received a church communication offering enthusiasm at the prospects of being able to gather again soon with other believers. This prospect has become a reality with the Republican-led state of my residence now lifting its shelter-in-place order. Such enthusiasm flies in the face of good sense and of all the best scientific data and opinions. There are places in the U.S. where death reigns wholesale due to the pandemic, and people of true belief—the potential liberators of our world—need a strong reminder not to be misled by the false prophets of capitalism. Every individual life has value in itself on which no one may ascribe a dollar amount. The role of true religious believers is to proclaim freedom from the oppression of slavery in whatever form it takes. Forsaking in-person gatherings at this time may threaten the purveyors of false hope, but for those who believe in a better tomorrow, it is a necessity that comes to each of us in the form of a dutiful obligation.

The May 2020 issue of Church & State magazine contains a number of articles relevant to this topic. To access it see here.