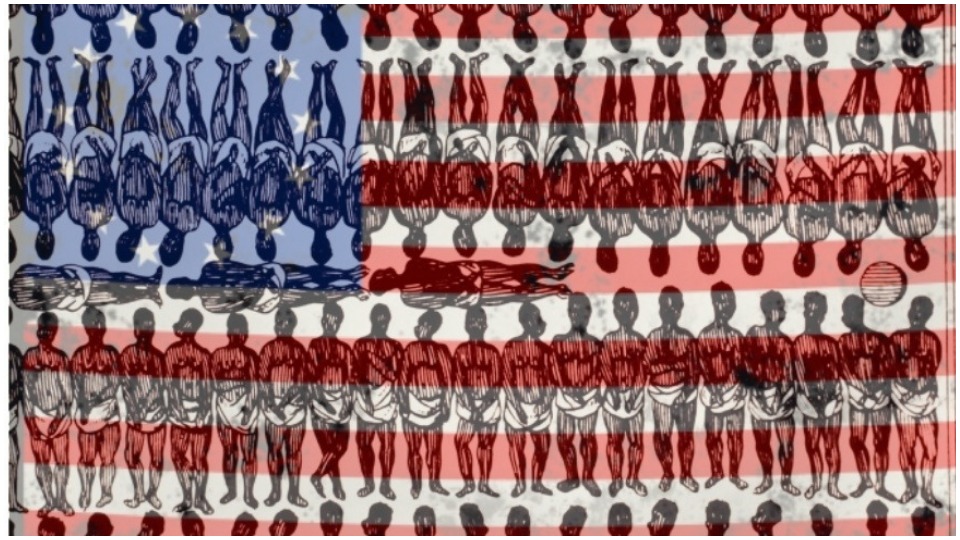

For generations, American schoolchildren have been taught tales of the heroic revolutionaries of 1776. The “Founding Fathers,” motivated by the ideals of freedom and independence, stood up to British colonialism and established a system premised on the principle that “all men are created equal.” The 1619 Project, initiated by the New York Times Magazine last August, is challenging this traditional origin story.

Instead of 1776, the project’s contributors argue we must look to 1619 to really understand the history of the United States. That’s the year 20 African slaves were brought ashore in Virginia, initiating centuries of forced labor, oppression, and racism for Black people on this continent.

The project, which was launched and anchored by Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones, upends the longstanding narrative that has portrayed slavery and the socioeconomic oppression and exploitation of Black people as merely regrettable episodes in an otherwise positive story of progress.

It consists of a series of essays, articles, and podcasts on a range of topics—from the myths surrounding U.S. independence and the slave plantation roots of modern American capitalism to theories about pseudo-scientific racial “differences” that still infect medical practice today and how the legacy of segregation continues to clog the streets of our cities with traffic jams, and more.

The common thread running through the contributions, which by design are written mostly by African Americans, is that they each place the Black experience—particularly of slavery—as the core around which the story of the United States really unfolded. As the project’s introduction states, “No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed.”

Since its launch in August, the project has set off a tidal wave of public discussion and debate, forcing millions to reconsider what they thought they knew about American history. With educational materials based on the essays of the 1619 Project being prepared and distributed to schools for use in their K-12 curricula, there is the potential that it could radically transform the way that the past—and present—is taught and understood in this country. Washington, D.C., Chicago, Newark, N.J., Brooklyn, and Buffalo, N.Y., are among the districts that have already signed on.

Many educators, journalists, and public figures have praised the project and its authors for prompting a mass re-thinking of not just the events of old, but the racial injustices of today, such as mass incarceration, unequal prosecution rates, poverty, health discrimination, and the still widening wealth and wage gap.

But the 1619 Project has not been without its detractors. From conservative quarters came charges that Hannah-Jones and others were out to “delegitimize America,” as argued by Benjamin Weingarten of The Federalist magazine. The Wall Street Journal published an essay by conservative Black commentator Robert Woodson that claimed the Times series actually hurt Blacks because it “wallows in victimhood and ignores success.” A group of five white historians wrote a joint letter to the Times complaining about what they portrayed as an attempt to “offer a new version of American history in which slavery and white supremacy become the dominant organizing themes.”

The latter have been joined and supported by writers at an outfit that calls itself the World Socialist Web Site, an ultra-left page that has long peddled in sectarianism and proclaims itself the organ of the Trotskyist “International Committee of the Fourth International.” The WSWS, employing a crude, pseudo-Marxist lens, argues that the 1619 Project is a “racialist morality tale” that “leaves out the history of the working class.”

From this class reductionist viewpoint, to place the experience of slavery at the center of U.S. history amounts to “toxic identity politics,” an unwitting advocacy of race war, and a distraction from the “struggle of wage labor against capital.” Minimized to the point of non-existence are any notions of multiple layers and forms of exploitation beyond (and in conjunction with) the labor-capital relation. No attention is given to the concept of super-exploitation that has been pioneered by other, less dogmatic, Marxists.

Cynically, the whole project is denounced as “one component of a deliberate effort” by the Democratic Party “to inject racial politics into the heart of the 2020 elections and foment divisions among the working class.” In this shallow and absurd analysis, the viewpoints of 1619 Project contributors are even said to bear “a disturbing resemblance to the race-based world view of the Nazis.”

Conservative ideologues, establishment historians, and ultra-left sectarians—it seems criticism of the 1619 Project has made for some strange bedfellows. They’ve coalesced to trash the project as a whole, but one statement by reporter Hannah-Jones seemed to galvanize all of them. In the introductory Times essay, she wrote:

“Conveniently left out of our founding mythology is the fact that one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”

For all the critics, challenging the accepted notion of why the American Revolution happened—and to argue that preserving slavery was a key factor for the establishment of the United States—was too much.

But one radical historian saw it coming. Dr. Gerald Horne says he was unsurprised that “the Wall Street Journal, certain Ivy League scholars, and certain ultra-leftists seemingly burst a blood vessel in their brains when the 1619 Project was unveiled.” Horne is the Moores Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston.

He says the re-examination of the American Revolution is part of a trend of second looks being given to past social transformations, starting with the Russian Revolution of just over a century ago.

“It was inevitable,” Horne says, “that the sharp reappraisals of revolutionary processes, most notably in the USA and focusing particularly on October 1917, would lead to a reappraisal of 1776.”

With a marked increase in the oppression of a range of peoples of color in the Western Hemisphere in the aftermath of the U.S.’ break from Britain, Horne says it’s difficult not to question the motivations of the founders of the new country. “The dispossession of indigenes and the enslavement of Africans increased after the formation of the USA,” he points out. Indeed, as an example, Horne draws attention to the fact that “as early as the 1790s the U.S. had replaced Spain as the major carrier of enslaved labor to Cuba.” Within 50 years, it was “ditto for the largest market [for slave labor] of all: Brazil.”

In fact, Horne has for some time been advocating a re-appraisal of the American Revolution not too dissimilar from that now being pursued by the 1619 Project. In one of his books published a few years ago, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America, Horne makes the argument that in the years before the Declaration of Independence America’s founders feared the clock was already ticking for slavery. Talk of abolition was advancing rapidly among policymakers in London, the imperial capital, but the even greater threat to the slaveholding colonial ruling elite was the danger of slave rebellion. It had already happened elsewhere in North America and the Caribbean.

Horne says that the widely feared possibility of a revolt by African slaves, coupled with external invasion, was the primary motivation for the colonial desire to break from Britain. Thus, in his viewpoint, 1776 amounted to a counter-revolution to preserve the right to enslave others.

If we want to understand how that conservative impulse to save slavery affects U.S. society today, Horne convincingly argues that we only need look at the legacy of white supremacy and anti-Black racism that still persists—on the job, in the courts, in the jails, in the schools, at the cashier’s desk, on the streets, and everywhere else.

The debate over the nature of 1776 is thus not simply a matter of historians squabbling over what motivated George Washington or Thomas Jefferson to start a new country. It is a struggle to comprehend—and change—the present by understanding how our society today is a product of those events and struggles of the past.

The 1619 Project is not just a story of how slavery shaped America; it is also the story of how the resistance and fights for liberation by Black Americans helped push the whole of U.S. society down freedom road. Reconstruction; fighting for desegregation in the armed forces, schools, businesses, and trade unions of the nation; the victories of the Civil Rights Movement, the protection of voting rights—just a few moments among many.

“The truth is,” Hannah-Jones wrote, “that as much democracy as this nation has today, it has been borne on the backs of Black resistance.” The Founding Fathers “may not have actually believed in the ideals they espoused,” she says, “but Black people did.”

This key takeaway from the 1619 Project—that the Black freedom struggle has been a driving force for the expansion of U.S. democracy—is the one that its critics cannot accept. The reaction of the conservative guardians of the status quo is predictable. Any suggestion that there is something illegitimate about the prevailing capitalist and racist power structures is beyond the pale for them.

The attacks of the ultra-left writers of the “World Socialist Web Site,” formulated on the grounds of a faulty and narrow version of Marxism, are perhaps more regrettable—especially because they distort an analytical approach that holds the potential for better understanding and changing the world in which we live. The legacy of Black advocates of socialism whose work was characterized by an understanding of how the dynamics of race oppression were central to the functioning of capitalism—figures like W.E.B. DuBois, Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, William L. Patterson, Angela Davis, and many more—is lost or twisted in these sectarian screeds.

It’s indeed true that the 1619 Project is not a fully formed socialist analysis of U.S. history or the political economy of chattel slavery. The project’s value is found in the way it has forcefully reminded millions of Americans of (or, more likely, introduced many of us to) the reality that the past we share is not necessarily what we thought it was.

“It is time to stop hiding from our sins and confront them,” Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote. “And then in confronting them, it is time to make them right.” The new understanding of our story as a country being pushed along by the Times series will now become a shaper of future struggles and of the history that is yet to be written.