Each Richard Wright novel in one way or another bears the imprint of his formative affiliation with the communist movement. His newly published The Man Who Lived Underground, a work that subverts capitalism by exposing its cruel distortions of humanity, is no exception.

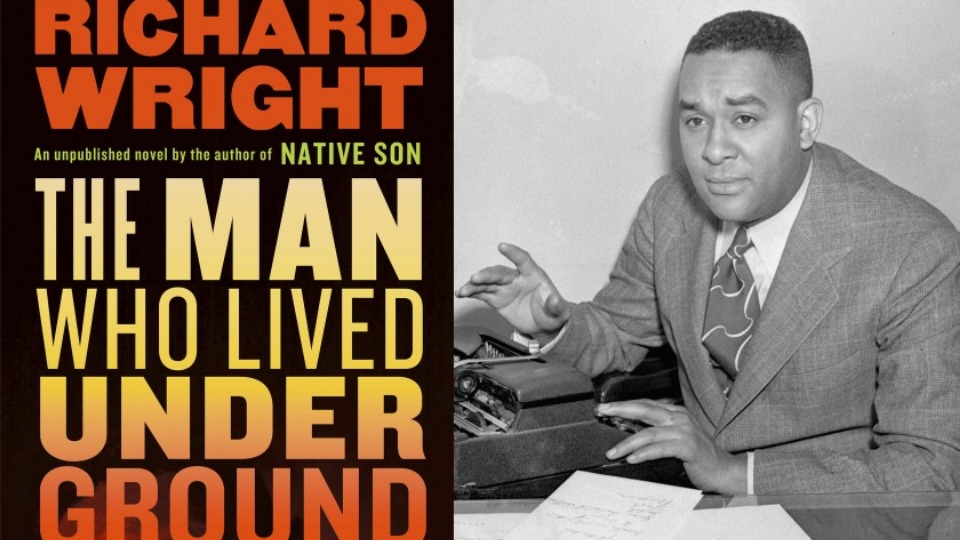

Wright completed The Man Who Lived Underground in December 1941. The first copies of the novel reached bookstores a month ago. The story behind the eighty-year publication delay is revealing.

In 1940, with Native Son still on the bestseller lists, Wright’s editors at Harper & Brothers saw a chance to leverage his success. They had a hunch that an uplifting tale with Wright’s name on it would be a hit and pressured the celebrity author for a new book under the upbeat title Black Hope.

Wright agreed to the idea and began a narrative about female domestic workers. But the Black Hope project languished. In 1941 he immersed himself in 12 Million Black Voices, crafting a nonfiction narrative to accompany a collection of 147 photos depicting stark realities of Depression-era Black life.

Wright was deeply affected by the book’s images of grinding poverty in the industrial North and “slavery by another name” in the Jim Crow South. Each of the faces in the photos—including lynching victims and chain gang convicts—could easily have been his face.

He dropped Black Hope to instead produce a novel about a crime more terrifying than the murder of Mary Dalton in Native Son but precisely equal in horror to the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

The disappointed editors and manuscript readers at Harper found The Man Who Lived Underground unsettling; one of them described the novel’s first fifty pages, in which three white policemen torture an innocent black man, as “unbearable.”

The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected in early 1942. There is evidence that the publishers feared the story would be too shocking for whites who did not wish to be reminded of their country’s history of racial violence. The editors likely sensed as well that, in the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor, readers might tolerate a message of Black Hope but not one of Black Lives Matter. In order to get an abridged version of the narrative published as a short story in 1944, Wright had to cut the police encounter entirely.

The new Library of America edition of The Man Who Lived Underground, lays bare the cultural nightmare of race-based police brutality. Officially published on April 20, the exact date of the verdict in the Derek Chauvin trial, the novel is already being called the most relevant book of 2021.

Part One takes place on a sweltering Saturday evening in an unnamed city. Fred Daniels has just received his weekly pay of seventeen dollars in exchange for odd jobs and lawn mowing at the home of the Wootens, an elderly white couple. “Tired and happy,” Daniels puts his money in his pocket and sets off on a homeward walk. He looks forward to an evening with his pregnant wife, services the next day at the White Rock Baptist Church, and returning to work “renewed” on Monday.

When Daniels notices three policemen observing him closely from a patrol car, he feels no fear. He knows he has done nothing wrong and that the Wootens and his church minister will vouch for him.

What follows is an atrocity of a type only now being publicized by bystander cellphones.

“Come here, boy.”

“Yes, sir,” he breathed automatically.

Quickly the door of the car swings open and three white policemen—Lawson, Johnson, and Murphy—step out and advance to confront him. “What you doing out here?…What’s your name?…Ever been in trouble before?…Where you think you’re going now?…Where you live?…Who you live with?”

Less than a minute into the encounter, Daniels has submissively answered these questions. Nevertheless, the terror begins. “We’d better drag ’im in, Johnson,” Lawson says.

At this, “a spasm of outrage” surges in Daniels. He reflexively pulls backward from the police, “hurling himself away,” but “their fingers tightened about his wrists, biting into his flesh; they pushed him toward the car.”

The life of Fred Daniels is now in the hands of the state. Accused of murdering a white couple in the home next door to his place of employment, he is police property. “Well boy, we’re going to keep you…until you tell us what you did.”

In the bloody next stages of the encounter, Daniels is driven to the police precinct, locked into an interrogation chamber, and beaten to unconsciousness. When the DA appears, the Black man’s limp body is tortured back to cognizance so he can sign a confession. He is too weak to hold the pen and the DA directs his hand across the paper.

Eventually, the police drive Daniels to the scene of the murder, then to his home. Among neighbors and even in the presence of his wife, the prisoner realizes that his world is altered. With the bullying officers hovering, he no longer has a place among the free. It dawns on him that living within the rules means nothing; he can have neither autonomy nor full humanity. Possessing every faculty of dignity, he will nevertheless “die a reasonless death.”

When Daniels embraces his wife under police surveillance, the circumstance carries trauma that brings on her labor. In a scene illustrative of state control, the officers lead the Black family to a patrol car and drive them to the hospital.

Momentarily left alone at the hospital waiting room, Daniels escapes out a window. Now a fugitive, he sees a half-open manhole cover and lowers himself, plunging into the darkness of a subterranean world where a second transformation takes place, this time with clear Marxist overtones.

As Part Two begins, Daniels is nearly asphyxiated by a flood of grey filth and a rotten stench of waste. A dead Black infant floats by him, and a blind rat is batted away. In the sewer, Daniels must steal to survive. But this seemingly surreal existence is after all not categorically different from that of Bigger Thomas in Native Son or the lives photographically depicted in 12 Million Black Voices.

The key difference is that the underground perspective allows Daniels furtive glimpses of the aboveground world. Initially, he hears a Black choir singing in “melancholy renunciation” and peers into a sunken basement church. He feels no racial solidarity and is alienated by their surrender, discerning “a defenseless nakedness in their lives that made him disown them.”

Later he observes the office of a real estate firm that collects hundreds of thousands of dollars in rent from poor Blacks. He steals money, then uses glue to subversively paste up hundred dollar bills as wallpaper for his underground hideout.

Foraging beneath the city for three days, Daniels acquires a cache of symbolic objects that he carries magician-like in a kind of bottomless sack. Along with cash, he steals food, a typewriter, a radio, a set of tools, a meat cleaver, a loaded gun, gold watches, jewels, and diamond rings, sensing that these objects carry a message: “They were the toys of the men who lived in the dead world of sunshine and rain he had left, the world that had condemned him.”

Realizing also that aboveground life is “something less than reality,” he defies materialism and demonstrates that defiance by making a heap of diamonds on the floor, then smearing them with the sewer slime oozing from his shoes.

His rebellion is implicitly collectivist: “A strange and new knowledge overwhelmed him; He was all people and they were he; by the identity of their emotions they were one, and he was one with them.”

Suddenly it seems imperative that he surface and share his knowledge. The novel becomes in part a conversion narrative. “He would rise up…walk forth and say something to everybody.”

Richard Wright often acknowledged that The Man Who Lived Underground was his favorite among his novels. An essay included in the new edition suggests that the reason was personal: “I know how it feels to be accused without cause.… It is one of the most agonizing, devastating, blasting, and brutal experiences conceivable. The man who has been accused of a crime he has not committed…is trying to fight for his status as a human being.”

The new edition also includes an afterword by Malcolm Wright, the author’s grandson, who enlarges this personal significance by explaining how the Black body, in general, is still systemically destined to “serve the needs” of law enforcement: “Should they [the white police] need to mock and feel superior, he serves that purpose. Should they need a culprit for a murder, he is there. Should they need to erase evidence of their corrupt behavior toward him, his skin is there to be perforated with bullets.”

The resurrection of Fred Daniels from the underworld, in an attempt to teach the very police who have abused him, ultimately fails. American fascism dictates that the people’s emissary be silenced. At the novel’s close, the policeman Lawson asserts, “You’ve got to shoot his kind. They would wreck things.”

Richard Wright

The Man Who Lived Underground

Library of America, 2021

240pp., $22.95

also available in Kindle and Audio CD

ISBN 10-1598536761

Comments