In November 1998, I published my first article in the People’s Weekly World, the print forerunner of the People’s World. Entitled “Time to disavow 175-year-old Monroe Doctrine,” the piece outlined the history of this seminal foreign policy, the centerpiece for two centuries of U.S. relations with our neighbors to the south.

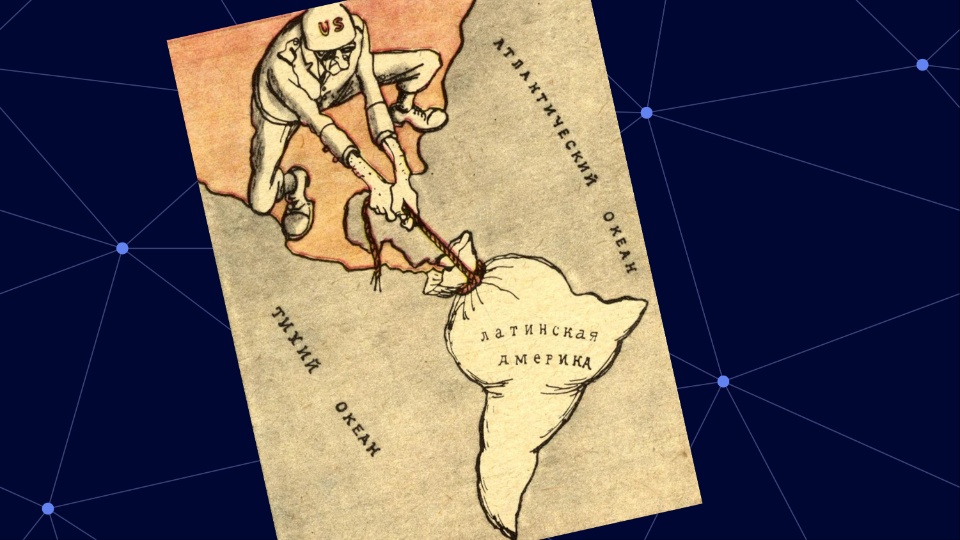

Drafted in 1823 by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and included in President James Monroe’s annual message to Congress, the Monroe Doctrine has led to military interventions throughout the region, subversion of national governments, support for the richest and most despotic classes, the oppression of millions of Indigenous peoples as well as those of African descent, and the propping up of numerous dictatorial regimes.

Yet, even with the vast changes that took place in the world during the intervening years, between 1823 and 1998, as I pointed out a quarter of a century ago, the Monroe Doctrine still lives.

(For an extensive list of U.S. military interventions and other activities in Latin America between 1846—the beginning of the Mexican-American War—and 1996, see Mark Rosenfelder’s survey here.)

What was true of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, 1846, or 1998 remains true in 2023, its 200th anniversary.

This is no more evident than in the ongoing criminal economic blockade of Cuba. For over 60 years, the United States has tried every trick in the book to overthrow the Cuban Revolution. The steadfast resistance of the Cuban people and government led by the Communist Party shows that our neighbor only 90 miles from our shores will never surrender.

Even though President Barack Obama re-established diplomatic relations and made a few small steps to normalize economic activities, his two successors have gone backward toward a more adversarial stance.

And at the same time, the United States not only maintains but intensifies sanctions against Cuba, as well as Nicaragua and Venezuela.

But much has changed both in Latin America and in the wider world in the last 25 years that makes the call for the U.S. government to disavow the Monroe Doctrine as timely as ever.

From Mexico to the Magellan Strait at the tip of South America, people are standing up and demanding that they determine their own destiny, one not determined by the Colossus of the North (or the “Yanquis” as the United States is often called in the region.)

The most prominent changes took place in five countries—Venezuela, Nicaragua, Brazil, Bolivia, and Mexico.

In Venezuela in 1998, Hugo Chávez, a military officer, initiated the Bolivarian Revolution (named for Simón Bolívar, the great South American liberator). “Our voice is an independent one,” Chávez said, “representing dignity, the search for peace, and the reformulation of the international system…to denounce persecution and the aggression of hegemonistic forces on the planet.”

Venezuela is still working to solve the problems of poverty, racism, and a whole litany of ills caused by capitalism. Chávez did not live to see his dreams come to fruition, but today, Venezuela remains resolute to his ideals, even in the face of sanctions and political threats directed from Washington against its revolution.

Nicaragua, the home of the Sandinista Revolution led by Daniel Ortega in 1979, has also seen an ongoing struggle with American imperialism. After being ousted by right-wing forces in an election in 1990, Ortega was re-elected president in 2006.

After two unsuccessful campaigns for the presidency of Brazil, Luis Inàcio Lula da Silva, known as “Lula,” the leader of the Workers Party, emerged victorious in 2002. Implementing a program of land reform and measures to improve the lives of the urban poor, he won a second term in 2006.

On the international stage, Lula was instrumental in the establishment of BRICS (an international organization dedicated to empowering the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and later South Africa). After he left office, and a series of political twists and turns too numerous to mention here, he was re-elected to a third term in 2022, beating the ultra-rightist Jair Bolsonaro (the Brazilian Trump wannabe).

In Bolivia, Evo Morales, a trade unionist and socialist, was elected president in 2006, the first Indigenous person to gain that office in 500 years of European settlement. Under his leadership, his political party, the Movement for Socialism (MAS), undertook important reforms toward improving health care, alleviating poverty, and controlling the wealth coming from the country’s many mineral resources.

After elections in 2019, Morales was ousted in a legal coup engineered by right-wing forces and exiled. After militant nationwide resistance, the successor government surrendered power, and the MAS returned to power under Luis Arce.

In Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as “AMLO,” and the MORENA movement was elected in 2018. Committed to replacing the neoliberal policies of previous governments, MORENA calls itself a party that supports land reform, fights climate change, approves of same-sex marriage, and opposes any move to privatize the state-owned oil company, PEMEX.

With AMLO barred by the Mexican constitution from running for a second term, MORENA has nominated Claudia Sheinbaum to run in 2024.

A short article cannot go into detail about every progressive government that has won power in Latin America over the last two decades, part of what has been known as the “pink wave,” which has ebbed and flowed at various times.

But among them are (with their current president in parenthesis): Argentina (Alberto Fernández), Chile (Gabriel Boric), and Colombia (Gustavo Petro).

In Ecuador, Rafael Correa was elected to three terms but retired in 2017. His successor has turned the country sharply to the right. In Honduras, Manuel Zelaya was overthrown in a 2009 coup supported by the United States. In elections held in 2022, Xiomara Castro won; she established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China.

In Peru, Pedro Castillo, a teacher, union leader, and reformer, won election in 2021 but was removed in a “legal coup” in 2022. Massive demonstrations across the country, particularly by the Indigenous people, have been unable so far to return him to power.

In the last 20 years, the countries of the region have stepped up efforts at economic cooperation and integration. Foremost among these is CELAC, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States. Consisting of 33 countries, it is a counterpoise to the Organization of American States (OAS), created by the United States.

It works closely with the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA), or CEPAL in Spanish. Among the many areas of common endeavor, both organizations are committed to bolstering the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and demand stronger actions on climate change from the developed countries.

In addition, Latin American countries are playing a larger role on the international scene. As mentioned, in 2006 Brazil was one of the founders of BRICS, established, as one observer noted, to be an “alternative to the U.S.-led international order, with the goal of offering growing countries in the Global South a counterbalance to Western institutions.” Among its major achievements was the establishment of the International Development Bank, dedicated to providing financial assistance to developing countries.

In 2024 Argentina will be one of six new countries to join BRICS. Bolivia, Cuba, Honduras, and Venezuela have applied for membership, but their applications are still pending.

One can see, therefore, that the world has changed dramatically since my first article in 1998. Yet, in many ways, American imperialism has not. Washington sees Latin America as existing within its “sphere of influence,” which means that U.S. intelligence agencies, information services, the Pentagon, and economic assistance programs are always hard at work making sure that no country in the region strays too far from their control.

The U.S.’ role is unsustainable and an impediment to worldwide peace and progress. Instead of constant confrontation, the U.S. government should pivot to a policy of cooperation with all its neighbors in this hemisphere.

My conclusion 25 years ago remains valid today: “What we need is a foreign policy in the Western Hemisphere that is based on equality, mutual respect, and non-interference in the affairs of other nations. This region [and may I add the whole world] would be better for it.”

As with all op-eds published by People’s World, this article reflects the opinions of its author.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!