While the vast majority of the world’s scientists agree that the universe started with the Big Bang, no one has actually seen it, since it happened nearly 14 billion years ago at what most assume to be the beginning of time.

No one has seen it until now, that is.

“In a few years from now,” wrote B.S. Sathyaprakash, of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Cardiff University, on his webpage, “a network of kilometer baseline laser interferometric detectors of gravitational waves will be in operation opening a new window onto the universe.”

These “detectors,” essentially a super-strong telescope, to be constructed nearly half a mile below the earth’s surface and more than a mile in length, may be able to look far out into space, and into the distant past, to see the Big Bang and, possibly, to determine whether any universes existed before our own.

Scientists have long understood that gazing into the night sky is actually a look into the past. While light travels extraordinarily fast – the speed of light – it does take time to cross vast distances. Thus, when looking at a star that is one light year away from the earth – that is, the distance it takes light to travel in a year – the viewer actually sees a star as it was a year ago.

The closest star is more than four light years away. The further away the star viewed, the further into the past the viewer looks.

The new Einstein Telescope is so powerful that it should enable study, instead of light, gravitational waves, inferred to exist by indirect evidence. These waves are thought to ripple through the universe as curves in space and time. The new telescope should be able to pick up the waves from the Big Bang.

In addition, it will likely allow scientists to see, for the first time, black holes and even into neutron stars, the extremely compressed remains of stars that experienced supernovas. Perhaps most exciting to scientists is the possibility of picking up trace waves from theorized previous Big Bangs – which could mean that our universe was not the first.

In addition, the telescope would be able to help scientists better understand the nature of gravity itself.

“These detectors would facilitate to test many predictions of Einstein’s theory of gravitation and would help to understand the formation of black holes and neutron stars,” wrote Sathyaprakash, “late stage evolution and end state of binaries consisting of black holes and/or neutron stars and the nature of the universe at the earliest moments of its creation.”

The project is not the first to attempt to study gravitational waves. However, previous attempts have encountered interference due to objects on and around the earth. The new telescope’s proponents, however, believe that it will encounter far less “noise” because it will be so far under ground. Another attempt, a collaboration between the European Space Agency and NASA, was jeopardized by U.S. budget cuts.

Scientists, under the auspices of the European Gravitation Observatory, will meet in Pisa, Italy, to determine exactly where the new telescope should be built.

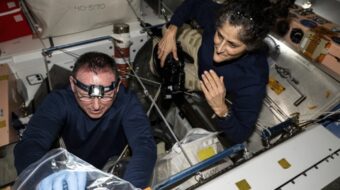

Image via NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.