GLASGOW—As some world leaders descend on Glasgow (and others stay away), our city will host a summit that has no treaty to agree but which will nevertheless be closely scrutinized to see whether the world, particularly those who run its dominant economies, are showing any signs of facing up to the crisis that is engulfing the planet.

It is a crisis that will be felt most quickly and most acutely in the global South and by the world’s poor. These are the people who do not account for most of the world’s greenhouse emissions but will be on the sharp end of its effects, whether directly through extreme weather events or indirectly if lives are affected through the economic impacts of an unjust transition.

A massive gap still exists between what is being promised by 2050 and the national plans to reach the necessary milestones on that journey by 2030. The reasons for this are political and rather obvious. Pledges made about 2050 targets stretch far beyond the political lifespan of all but the most optimistic politicians.

Hitting 2030 targets requires an intensification of action now.

But there are few politicians anywhere who would prefer action now. There are very few—possibly no—world leaders who were elected or came to power delivering the program of economic and social transformation that is really required to make the change we need. The politicking is deafening, but the plans for action are much less pronounced.

For months now governments, not least our own in Scotland and the U.K., have been gearing up for announcements to shine a rosy light on their record and future plans. This greenwashing is only matched by the corporations who are spending millions on propaganda but have thus far shown themselves to be totally inadequate in face of the challenge.

Brace yourselves for another period of positivity, but watch closely to see what really emerges from a summit which should, both because of the climate emergency and the global pandemic, be tearing up the playbook, but which in reality will be unlikely to make significant progress.

If there is hope, it will manifest outside the steel fences of the official conference zone.

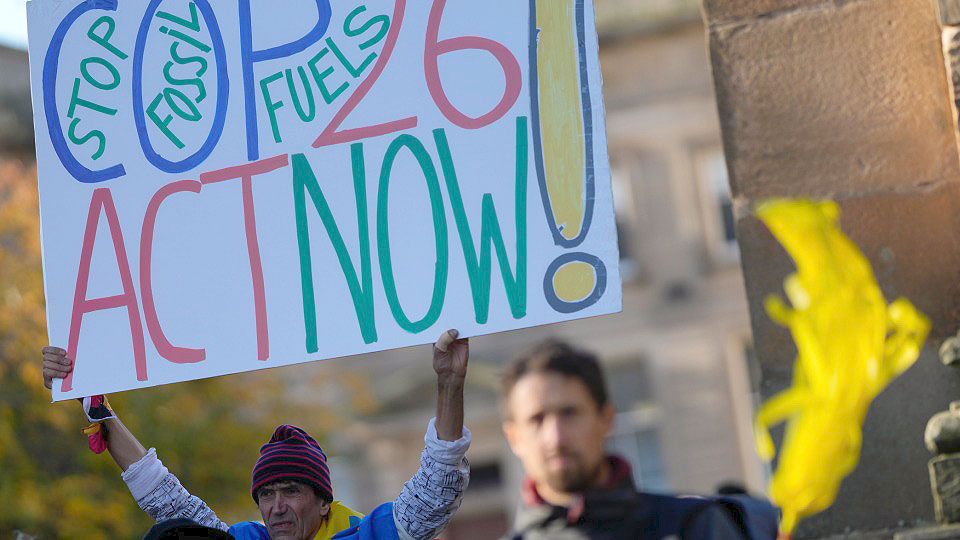

The demonstrations and political events organized by the COP26 Coalition, which includes trade unions, environmentalists, anti-poverty groups, and a whole host of campaigning organizations, are where the important debates will be.

These events may not be as large as at some previous COPs, due to the pandemic, but they will still serve to show that powerful alliances of people continue to be forged. Many of the events will also be digital and beamed around the world.

It would be easy to imagine from the statements of various local and national politicians that the most important thing about COP26 is that it serves as a showcase for Scotland and Glasgow in particular.

Workers and campaigners have been chided not to misbehave and to play their part in projecting a picture of life in Glasgow to wow the visitors and the onlooking world. What seems to matter less is whether the picture is accurate or not.

Glasgow and Scotland are not unique in the world in terms of poverty, wage inequality, cuts to services, and inadequate public transport. But the fact that we are not unique cannot disguise the fact that these are problems we have.

And I just don’t believe ordinary people are buying into the idea that this is primarily a showcase moment—not for Glasgow, not for Scotland, and not for the U.K.

The truth is that most of the world’s leaders see the climate crisis as largely unconnected to their wider economic and social policies and programs. They certainly show little conception of the inevitability of climate change in a neoliberal global world economy, just as they fail to recognize the impact of financialized capitalism on the lives of workers.

The challenge of climate change requires a fundamental rebalancing of power between the asset-wealthy and the wage-poor. It is why the failed model of private ownership in key sectors such as energy and transport must be abandoned and why we need public programs of house-building and deep retrofit.

It is why we require decent public services and dignity and respect for the workers who deliver them. Unions are quite rightly using the leverage provided by the politicians’ obsession with showcasing and spin to push for decent pay. But the importance of building workers’ power goes much deeper than that.

Taking inspiration from the Lucas Plan—a 1976 plan for a just transition written by armaments workers themselves who wanted to produce “socially useful products” rather than weapons—workers have the potential to be the driver of industrial de-carbonization, whether in energy, manufacturing, transport, or public services.

Last week, Scotland’s rail unions launched A Vision for Scotland’s Railways, a plan that could contribute massively to reducing transport emissions. These same rail unions had recently won in a pay dispute with Scotrail after balloting for industrial action.

These two moments are not separate, they are linked.

If cleaning and other local government workers take industrial action during COP26, they will be supported by the figurehead of the environmental movement, Greta Thunberg. When the youth climate strikers take action on November 5, trade unions will be there.

There is a growing recognition that meeting climate targets requires a just transition and that a just transition requires a growth in workplace power and the democratization of industry.

Of all the messages that come out of COP26, this may turn out to be the most important and the most enduring.