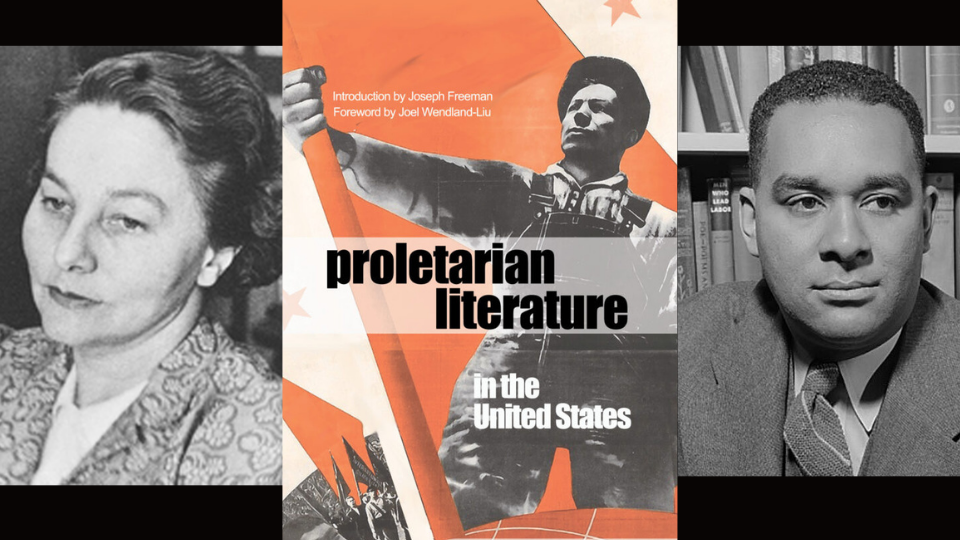

Within the electric pages of Proletarian Literature in the United States, Taggard’s “Interior” and Wright’s “Between the World and Me” engage in a profound dialogue. Both explore the individual’s stance toward social conflict—Taggard’s woman insulated in her “middle class fortress,” choosing to ignore society’s problems, and Wright’s vivid depiction of a lynching’s aftermath, refusing to be ignored. Together, they challenge the reader to confront systems of oppression, arguing that neutrality in injustice is impossible.

The lyrical poem, “Interior,” which appeared only in Proletarian Literature in the United States, is a sonnet. Lyrical poetry tends to emphasize emotional states through imagery and meter without focusing on telling a story. In this sonnet, somewhat disguised by refusal to adhere to the rhyme scheme of the traditional format, along with the false fifteen lines created by the exaggerated line after the poem’s long fourth sentence, “the story” is that the subject of the poem refuses to engage with social conflict and instead hides in their posh home. But this story isn’t a linear developing plot; it is an impression created by images. Further, sonnets, depending on style, contain what poets call a “turn.” Shakespeare typically used the final two lines of the poem to resolve or comment on the subject matter. Another style, known as Petrarchan, placed this “turn” in the ninth line. A famous modern example of this style is “If We Must Die,” by Claude McKay.

We often associate the sonnet form with a rigid style of old-timey English writers like Shakespeare and Milton. But in the early 1900s, modernist poets, among whom Taggard was closely associated for the previous 15 years, had returned to the sonnet. There are at least two other examples in the poetry section of PLUS, one by Alfred Kreymborg called “American Jeremiad,” and another by Joseph Freeman titled “To the Old World.” Taggard’s use of the sonnet also reflected its more common appearance in the modernist movement at the time. T.S. Eliot had tucked a sonnet into his modernist epic The Wasteland, and others closer to Taggard’s world, such as Lola Ridge and Edna St. Vincent Millay, were including many in their collections. The classic anthology of poems protesting the state murder of Sacco and Vanzetti, titled America Arraigned! included many.

Taggard had grown up in a missionary family in Hawai’i before World War I. She went to New York City in 1920, taking a job as an editor with the publishing company B.W. Heubsch. She was tasked with promoting a new book of poems called Sun-up and Other Poems, by Lola Ridge, a rising star in modernist poetry whose revolutionary verse and organizational skills put her at the forefront of the left wing of the modernist movement. Taggard’s own poems soon after began to appear in The Liberator, The Nation, Century, Dial, Poetry, and a host of other smaller publications.

Striking out on her own, Taggard published May Days in 1925, a spectacular anthology of about 300 radical poems from the radical journals The Masses and The Liberator. By 1922 or 1923, The Liberator was staffed almost exclusively by Communist Party members. Financial difficulties caused it to fold in 1924. It was replaced by Workers Monthly in 1925, which also served as the official organ of the Workers Party of America, the legal front for the banned Communist Party. In her introduction to May Days, Taggard praised Workers Monthly’s cultural significance. In 1926, the cultural staff of Workers Monthly separated and formed the New Masses, while the political section remained to transform Workers Monthly into the policy- and theory-based The Communist in 1927. Taggard became a contributor to the New Masses in 1926, the same year her poetry collection Words for the Chisel was published. Later, she became a college English literature professor and wrote an excellent, if non-political biography of Emily Dickinson, a subject to which her poem “Interior” may hint.

The speaker in “Interior” depicts a middle-class woman (“race” unspecified) whose life is sheer boredom, a life she has grown to hate. The traditional purpose of the form was to elevate or praise a worthy subject: a patron, a lover, a sublime scene, a beautiful idea. For the modernists, the intent was more internal or individual but equally groundbreaking, such as a newly discovered revolutionary intent. In this poem, however, the idea that is elevated is one of waste. The speaker appears to be speaking urgently, if indirectly, to the woman, telling her what seems obvious to both: that the emptiness and uselessness of her existence have a remedy. She could reclaim meaningfulness by joining the rising tide of proletarian struggle in the streets. But, speaking for the subject, the speaker, in the closing two lines, observes her unfortunate continued silence.

In American discourse, it was—and remains—common practice to specify markers of diversity only when the holder of those identities varies from the perceived dominant norm. In other words, if the poet intended us to imagine the woman as a Black woman, images of the subject would be made to render this element perceptible in the poem, even if subtly. Taggard may imagine the raceless woman in “Interior” to represent a de-ethnicized class type of person who experiences viscerally experienced forms of gender oppression—clearly signaled in the poem—but whose love for the security of wealth in a “middle class fortress” and idleness enables her capitulation to the subjugation of patriarchy.

The mood and message of “Interior” sharply contrast with the intense horror of Richard Wright’s “Between the World and Me,” which appears a few pages later. Both poems, however, explore a theme of the speaker’s or subject’s relationship to social conflict. If the subject in “Interior” has no desire to get involved with the “outside people” who “work and sweat” and are “cheated,” Wright’s speaker initially views the pile of human remains from a recent lynching only with “cold pity.” But in “Between the World and Me,” the stance of the distant onlooker quickly shifts.

At the time of publication, Wright, who later became famous for his best-selling novel Native Son, his groundbreaking collection of short stories, Uncle Tom’s Children, and the photodocumentary collaboration with Edwin Rosskam titled 12 Million Black Voices, had only been devoted to the profession of writing for about three years. Laid off from his job as a postal clerk during the early years of the Great Depression, Wright joined one of the Chicago-area John Reed Clubs, Communist Party groups that supported writers, in 1932. Along with other soon-to-be prominent Black writers like Theodore Ward, Arna Bontemps, Margaret Walker, Edward Bland, and Frank Marshall Davis, Wright, still in his early twenties, formed the South Side Writers Group the following year. “Between the World and Me,” a poem that echoes the naturalist setting, long anaphoric lines, and repetitive, cataloging language use in Walt Whitman’s work, was published nearly simultaneously in the John Reed Clubs-affiliated journal Partisan Review.

Walt Whitman, best known for his Civil War poems that document the fight to end slavery, rejected the false idea that art exists separate from social conflict or struggle. Left-wing poets have long admired him. In one of his earliest published essays, “Towards Proletarian Art,” Michael Gold called his generation of radical writers “Walt Whitman’s Spawn.” The John Reed Clubs took Whitman’s advocacy further, announcing “Art is a weapon in the class struggle.”

The title, “Between the World and Me,” comments on the first line of chapter one in W.E.B. Du Bois’s major book, The Souls of Black Folk, which states: “Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: …How does it feel to be a problem?” Du Bois’s point in 1903 was that the white pretense was that Black people caused social conflict in the U.S., when anti-Black racism came from Euro-Americans who insisted on maintaining a system of white supremacy. The violence of lynching was the all-too-common, peak expression of that system.

This is the scene upon which the speaker “stumbles.” Horrific images: “a design of white bones,” a burnt tree “pointing a blunt finger accusingly at the sky,” remnants of clothing, a pile of ashes of human remains, the eerie presence of a staring human skull, and other evidence of a crowd of participants and onlookers: “cigars and cigarettes, peanut shells, a drained gin-flask, and a whore’s lipstick.” Evidence “of tar, restless arrays of feathers” and an odor of gas attests to the torture, still recent enough to linger in the air, that set the stage for the killing.

The scene freezes the speaker into “cold pity for the life that was gone.” This existential posture of unmoving stasis mirrors the silence effect in “Interior,” when we discern that the middle-class, house-bound woman chooses silence when asked to figuratively speak up on behalf of the people struggling to survive. The speaker, who is explicitly identified as Black only in the final stanza (“my black wet body”), may want to share in the idle privilege of ignoring the social conflict that is represented in the scene with which he is confronted. Perhaps, other than “cold pity,” he would like to retreat to the security of a “middle-class fortress” where such scenes can be rendered abstract and disassociated.

No such choice exists. Immediately, the natural setting shifts, and the quiet air changes. The human remains, the vegetation, even the ground itself, reach out to the man and trap him. The human remains seem to melt into his body, and “a thousand faces” eager for another lynching surround him, beginning to torture him. Wright’s speaker experiences the same violence. The poem shows how lynching is not just a one-time extremist act but part of a recurring pattern of collective punishment that targets Black people randomly and broadly, pretending they are America’s unresolved problem.

For Taggard, the woman’s decision to ignore social conflict and submit to patriarchy is based on privileges granted by class. This privilege directly relies on the systematic exploitation of the “cheated people” who are now demanding power and freedom. Wright offers a clear counterpoint: “class” cannot be separated from race—to put the conundrum simply—as long as “the thing” exists “between me and the world.” Racism is a form of unavoidable collective punishment for Black people, but white supremacy also creates an inescapable reality for Euro-Americans. As long as white supremacy supports capitalist growth and the class power of the capitalists—with eager participation of the “thousand faces” or the dreaded abstention of the woman in “Interior”—its violence will continue, implicating the complicity of those who cling to whiteness.

The contrast between Taggard’s and Wright’s poems reveals a core tension in U.S. social life. “Interior” and “Between the World and Me” show two sides of systemic oppression: one depicting internalized surrender to a meaningless life, the other showing brutal punishment for those denied protection. Taggard critiques the privilege that enables disengagement, while Wright exposes the violence that forces engagement for survival. Together, they powerfully indict racial capitalism, linking social violence with passive complicity. By placing these perspectives side-by-side, the collection argues that liberation must confront both active terror and silent acceptance that sustain injustice.

Interior

By Genevieve Taggard

A middle class fortress in which to hide!

Draw down the curtain as if saying No,

While noon’s ablaze, ablaze outside.

And outside people work and sweat

And the day clings by and the hard day ends.

And after you doze brush out your hair

And walk like a marmoset to and fro

And look in the mirror at middle-age

And sit and regard yourself stare and stare

And hate your life and your tiresome friends

And last night’s bridge where you went in debt;

While all around you gathers the rage

Of cheated people.

Will we hear your fret

In the rising noise of the streets? Oh no!

Between me and the world

By Richard Wright

And one morning while in the woods I stumbled

suddenly upon the thing,

Stumbled upon it in a grassy clearing guarded by scaly

oaks and elms

And the sooty details of the scene rose, thrusting

themselves between the world and me….

There was a design of white bones slumbering forgottenly

upon a cushion of ashes.

There was a charred stump of a sapling pointing a blunt

finger accusingly at the sky.

There were torn tree limbs, tiny veins of burnt leaves, and

a scorched coil of greasy hemp;

A vacant shoe, an empty tie, a ripped shirt, a lonely hat,

and a pair of trousers stiff with black blood.

And upon the trampled grass were buttons, dead matches,

butt-ends of cigars and cigarettes, peanut shells, a

drained gin-flask, and a whore’s lipstick;

Scattered traces of tar, restless arrays of feathers, and the

lingering smell of gasoline.

And through the morning air the sun poured yellow

surprise into the eye sockets of the stony skull….

And while I stood my mind was frozen within cold pity

for the life that was gone.

The ground gripped my feet and my heart was circled by

icy walls of fear–

The sun died in the sky; a night wind muttered in the

grass and fumbled the leaves in the trees; the woods

poured forth the hungry yelping of hounds; the

darkness screamed with thirsty voices; and the witnesses rose and lived:

The dry bones stirred, rattled, lifted, melting themselves

into my bones.

The grey ashes formed flesh firm and black, entering into

my flesh.

The gin-flask passed from mouth to mouth, cigars and

cigarettes glowed, the whore smeared lipstick red

upon her lips,

And a thousand faces swirled around me, clamoring that

my life be burned….

And then they had me, stripped me, battering my teeth

into my throat till I swallowed my own blood.

My voice was drowned in the roar of their voices, and my

black wet body slipped and rolled in their hands as

they bound me to the sapling.

And my skin clung to the bubbling hot tar, falling from

me in limp patches.

And the down and quills of the white feathers sank into

my raw flesh, and I moaned in my agony.

Then my blood was cooled mercifully, cooled by a

baptism of gasoline.

And in a blaze of red I leaped to the sky as pain rose like water, boiling my limbs

Panting, begging I clutched childlike, clutched to the hot

sides of death.

Now I am dry bones and my face a stony skull staring in

yellow surprise at the sun….

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!