WASHINGTON — Funded by Congress, contributions, and philanthropists—many of whom are or descend from corporate chieftains—the Smithsonian Institution, that complex of museums in and around the Nation’s Capital, usually doesn’t rock establishment boats.

Which is what makes a recently opened exhibit in the National Portrait Gallery, 1898: U.S. Imperial Visions and Revisions, out of the ordinary. If it doesn’t rock the entire boat, it certainly puts U.S. history through a heavy storm.

The Smithsonian has not tackled the entire history of U.S. imperialism, both on and off the North American continent. The curators admit that. Doing so would take a whole shelf-full of thick books. It also has little about labor’s role and reaction. We’ll get to that.

But within its limits, the Spanish-American War of 1898 and its aftermath, the exhibit presents evidence rarely seen in U.S. history books below the college level. And in red states like Florida, and especially Texas, whose whole-state centrally controlled K-12 textbook market is so large it can dictate what much of the rest of the country reads, imperialism isn’t there at all.

In short, what the exhibit does, it does well and leaves viewers with a lot of history to ponder.

The Spanish-American War, 125 years ago, began in April 1898 and ended with a treaty in December. The exhibit will be on display even longer: From late April to February 25.

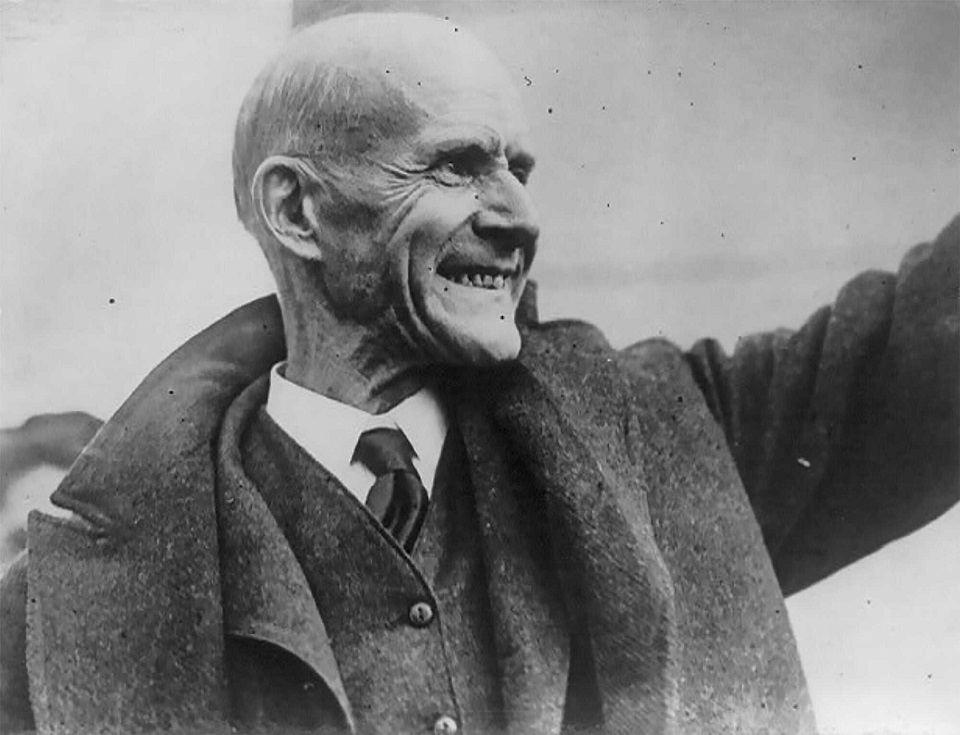

The war “took American labor by surprise” and was over before most leaders could react, H.B. Davis wrote in Science and Society in 1963, the most recent study of labor and the war found on the Internet. There were two exceptions: Eugene V. Debs and the Machinists.

“The American Federation of Labor has for so many years acted as an agent of the State Department and American foreign policy that we are inclined to forget its early anti-imperialism” and concentration solely on domestic affairs, Davis explained.

Debs “denounced the war while it was in progress,” Davis reported. Other union leaders privately agreed but dared not say so in those jingoistic times. The Machinists’ magazine, after it ended, “hinted darkly after the war that ‘the capitalistic system had been responsible.’” That was all.

Indeed, the ties Davis cited 60 years ago did not change until 2005. What was then U.S. Labor Against War convinced the AFL-CIO Convention in Chicago to denounce George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq. It still blasts other U.S. interventions. Some unionists want to end all ties with U.S. diplomacy.

Admit another bias

Smithsonian curators also admit another big bias: The exhibits’ items, drawn from its immense collections, reflect curatorial and indeed national attitudes—led by nativism and jingoism—of that era.

Other themes occasionally surface: The linkage between white nationalism and imperialism, propaganda from the “yellow press,” board games, and caricature of Afro-Cuban Blacks as inferior, for example. The role of unbridled capitalism gets mentions, about Cuba (sugar) and Hawaii (pineapple).

“Dollar diplomacy,” which occurs later, is unmentioned. “Gunboat diplomacy” is illustrated, with art of destruction of Spanish fleets in Santiago de Cuba and Manila Bay in the Philippines. That painting is jingoistic—and truthful. The U.S. fleet of impressive steel-plated warships parades by in a long straight line. Off to the left are smoking wrecks of the mostly wooden Spanish fleet it destroyed.

That’s the tenor of imperialism.

The 1898 war saw the U.S. “liberate” Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico from Spain. But it also annexed Hawaii that year and later took over Guam. In 1903, the U.S. literally created Panama, which had been a Colombian province, so the U.S. could dig the canal on its terms.

U.S. imperialism was founded on the 1823 Monroe Doctrine. That doctrine, 200 years ago, was passive, but first President Theodore Roosevelt and then the Navy, which he had largely built up, made it active after the war, with later U.S. intervention in Haiti (twice), the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Nicaragua, and Honduras.

Plus U.S. suppression of Puerto Rican and Filipino pro-independence revolts in the early 1900s. Plus fighting in Cuba between the classes. All classes welcomed liberation from Spain. They split over welcoming the U.S. protectorate: Upper classes, jealous of their wealth and trade ties, yes; Everybody else, incensed at the virtual U.S. right to invade anytime, no.

The exhibit deletes most prior U.S. mainland imperialism, though.

What’s out? The Mexican War of 1846-48, forced removals and obliteration of Native Americans—except for a Native American painting of the wipeout of Custer’s cavalry at Little Bighorn–the U.S. settlers’ 1835-36 revolution and 1845 U.S. annexation of the Mexican state of Tejas (Texas), “54-40 or Fight” which yielded the Pacific Northwest and the Idaho panhandle. And that’s a partial list.

It also omits recent and/or current evidence of past imperialism, such as the U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, originally a Navy coaling station. Hawaii and Guam were stations, too. Or the statement by Sen. S.I. Hayakawa, R-Calif., opposing the 1979 Panama Canal treaty, which returned the Canal and its zone to Panama: “We should keep it. After all, we stole it fair and square.”

Imperialism and condescension

A classic exhibit example of both imperialism and condescension: A Harper’s Weekly cover of a classroom where the only adult—the teacher—is Uncle Sam. He wields a birch switch over cowering kids: “Puerto Rico” “Cuba” “Hawaii” and “Guam.” Uncle Sam is supposedly tutoring them in self-government. A teenager in the corner wearing a dunce cap is labeled “Aguinaldo,” for Emilio Aguinaldo, leader of the long post-1898 Philippine independence revolt against U.S. rule.

The portraits and memorabilia, whose captions are used to detail history as well as individuals’ roles in it, range from Presidents William McKinley and especially Theodore Roosevelt to leading foes of imperialist adventures, including Mark Twain, W.E.B. DuBois, and Jane Addams, the founder of Chicago’s Hull House resettlement center for immigrants. But not Debs.

“I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons into any other lands,” Twain said. The destruction of the Wobblies (the Industrial Workers of the World) came later when they opposed U.S. entry into World War I.

There are also portraits and histories of resisters in the victims’ lands. Among them: Aguinaldo and Jose Marti, the Cuban independence leader killed in an 1895 battle in the third of three anti-Spanish revolts.

There’s also Roosevelt’s justifying the war as the U.S. imperialistic contest with Europe.

“If we will not fight for the blowing up of the MAINE…we are no longer fit to hold up our heads among the nations of the earth,” Roosevelt wrote after the battleship’s blast, which triggered the war. The nations Roosevelt was thinking of: European imperial powers Britain, France, and Germany.

Roosevelt also equated imperialism abroad to imperialism against Native Americans. “If white people were morally bound to abandon the Philippines, we are also morally bound to abandon Arizona to the Apaches,” TR declared during the 1900 election campaign.

Jingoist journalism gets its due: “SPAIN GUILTY!” one New York paper screams after the Maine blew up in Havana harbor. Investigations later showed bituminous coal, which could ignite spontaneously, was the culprit.

Foes of imperialism get one gallery of their own in the exhibit. It shows politics made strange bedfellows: Committed pacifists and anti-imperialists such as Twain and Addams led one wing. Sen. “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, D-S.C., led the other, white nationalists. Tillman argued conquest of Spanish-speaking lands would lead to the “degradation of the superior civilization.” One guess who he meant.

One odd omission, though, from the anti-imperialist pantheon: William Jennings Bryan. The “Great Commoner’s” second presidential campaign in 1900 was explicitly anti-imperialist, challenging the jingoism and nationalism of Republican McKinley and his opportunist running mate, Roosevelt. McKinley won, by 52%-46%, a smaller-than-expected margin over Democrat Bryan.

Oh well, you can’t include everything. Otherwise, this wouldn’t be an exhibit. It’d be a book—a big book. Details about the exhibit are here.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!