In the 1920s, teachers protested child labor. It was in Naugatuck, Connecticut, that educators saw students showing signs of tiredness in class and were unprepared for the lessons of the day. These educators focused on stopping the use of children to pull wagons of “homework.”

This was work, e.g. putting together safety pins, brought home from factories to add value, especially by women and children. The protests of these teachers, combined with the growing union movement of the depression years, stopped this onerous activity.

Tenure, imbuing certain job guarantees after a probationary period, has played an important role in protecting educators when participating in their workplaces and communities. Its roots go back to the even earlier nineteen hundreds. I learned about it quite by accident.

The year was 1973. I was among a group of young people attending presentations at the Community Church of Boston. First up was a man who had a deeply wrinkled, weathered face topped by a full stock of grey hair. From our perch on the world, he looked 100 years old. Abbie Hoffman, a youth leader, had told us to go home and kill our parents. Anyone over the age of thirty was to be mistrusted. Why should we listen to this guy?

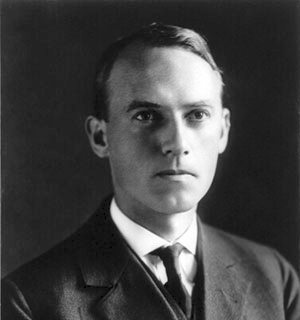

We were to find out, foursquare, that there were plenty of reasons to listen attentively. Before us was none other than Scott Nearing, defender of socialism, environmentalist, pacifist, and educator. This guru of the back to the earth movement of the 1970s, ardently anti-imperialist, and opposed to the then-U.S. War in Vietnam, was already an iconic figure of the 20th century.

As an educator he made a contribution that keeps on giving. Nearing went to college at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He became a professor of economics there. He followed data wherever it led. One place it led him was to investigate child labor in the shops and mines of Pennsylvania and beyond. Two million children were wage laborers in 1910. What this physical and mental fatigue was doing to children appalled him and others.

Nearing went to work. With the exactness of a scientist, he compiled data and drew an obvious conclusion to him. Child labor was an abomination that must be ended. But how do you go about such an undertaking? He certainly knew that children workers were generating enormous wealth for the one-percenters of the time.

Nearing was born into the coal and logging camp of Morris Run, Pennsylvania, in 1883. He had the good fortune to have engineers on both sides of his family and lived without want. His Mother home-schooled him until the age of thirteen. A poem, The Fence and the Ambulance that he read early in life had an outsized influence on him. Here’s the way he described its impact in his instructive autobiography, The Making Of A Radical (1972).

The theme was of a dangerous cliff from which people fell and were killed or badly injured. Kindhearted citizens subscribed to buy and maintain an ambulance at the foot of that cliff to take care of the victims. Others, however, demanded that a fence be built along the cliff so that people would no longer fall over. Social workers were those who operated the ambulance after accidents occurred. Radicals insisted on a fence. For years I subscribed, figuratively and literally, to the ambulance fund. Gradually I turned my thoughts and energies to fence building.

Eventually, combined with the bread and roses labor movement of 1912, this effort bore fruit in strict child labor laws. There were repercussions for Nearing. On the board of the University of Pennsylvania were representatives of the factory owners exploiting child labor. They had connections with the state legislature where a bill appropriating one million dollars for the university was pending. A manufacturer and prominent Republican contacted the University making it known that if they wanted to see the money, Nearing had to go. In spite of a mass movement in his defense, he was fired without cause after working at the University for nine productive years.

Scott Nearing was able to teach again at the University of Toledo, Ohio. When he opposed the U.S. entry into WWI in 1917, he was, once again, fired from his position. Members of the regional Labor Council on the board of the University stuck by him but to no avail. War fever was sweeping the country. His case is still sited in teacher tenure law.

June of 2015 marked the 100th year of Scott Nearing’s dismissal for defending children. He eventually joined the Socialist and Communist Parties. Eugene Debs called him the most outstanding teacher in the United States. The best way to commemorate this staunch protector of children is to defend teacher tenure, public education, the environment, and peace. Nearing would say, “There’s work to be done.”

Photo: Scott Nearing. | Wikipedia (CC)