The history of the Communist Party USA is a contested history consisting of two main camps—the “orthodox” and the “revisionists.” Where the “orthodox” historians see in the CPUSA nothing more than an appendage of the Soviet Union, the “revisionists” paint a more complex and nuanced picture; they often highlight the work of Communists at the grassroots fighting for workers’ rights, African-American equality, peace, and socialism.

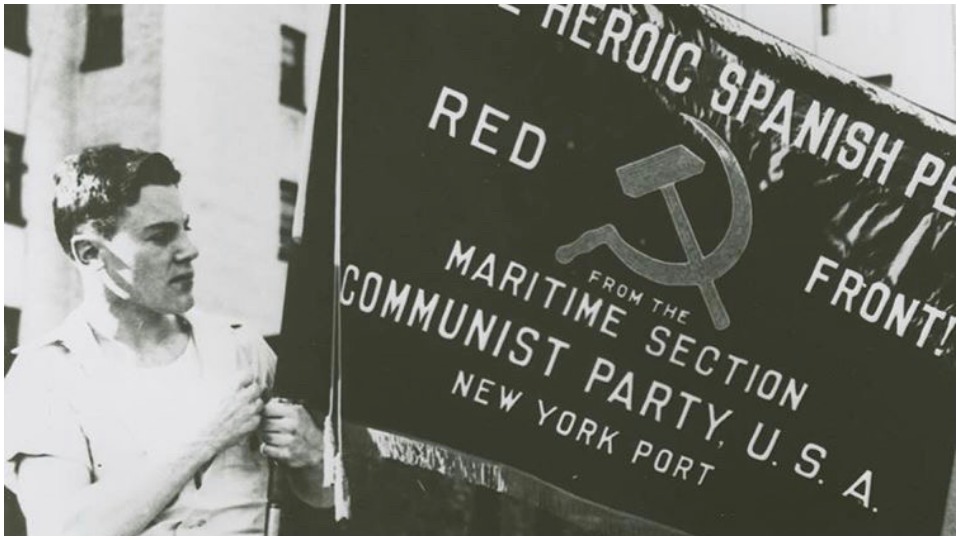

The role of the CPUSA in the formation of the U.S. labor movement is a contested history as well. The organizing of the East and West Coast waterfront unions is a part of this contested history.

Vernon L. Pedersen’s The Communist Party on the American Waterfront: Revolution, Reform, and the Quest for Power aims at resurrecting some of this contested and forgotten history. Unfortunately, though, Pedersen’s “orthodox” biases steer what would otherwise be a useful and informative theme into the murky waters of anti-communism. He even notes in the Introduction, “This study validates much of the orthodox argument.”

Pedersen’s research reflects his biases, as every attempt by the Communists to organize waterfront workers becomes a nefarious plot, a power grab, a Moscow-directed and -funded effort.

To him, George Mink, the leader of the Communist-initiated Marine Workers Industrial Union (MWIU), “was failing at only part of his job, the part requiring him to create a mass-based union. The other part, providing information to the Comintern [Communist International] and the [Soviet] intelligence services, was a smashing success.…”

In Pedersen’s narrative, we are taken far from the American waterfront. The Soviet Union, Germany, and Spain factor heavily into his story, which revolves around secret dispatches, secret funding, and secret meetings—“clandestine work” as it were.

Intrigue and murder are also part of Pedersen’s narrative. As he notes, Mink may supposedly have been responsible for multiple murders. The first, a killing in Germany of a sailor suspected of betraying a Soviet espionage apparatus, is linked to Mink, though Pedersen adds the qualifier a few sentences later, “The killing, if it happened at all.…” Additionally, Mink was said to have “personally orchestrated the assassination” of an Italian anarchist, and was rumored to have “been an enforcer for the secret police” in Spain, where Communists and broad left forces were fighting to defend democracy against the fascist Francisco Franco.

Even if Pedersen’s evidence regarding the murders weren’t rumor and hearsay, which they are, what do they have to do with U.S. Communists trying to organize waterfront workers? Other than to illustrate his anti-communist, “orthodox” biases?

While Pedersen does provide some useful information on Communist initiatives to organize waterfront workers, his history is marred. Of particular interest to this reader is Pedersen’s brief review of the Interclubs, a housing, restaurant, and recreational network set up by Communist cadres in port cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Norfolk, New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco that served as organizing centers for waterfront workers and seamen—and often acted as the genesis for nascent unions. To Pedersen, the understaffed and underfunded Interclubs, which were attacked by conservative unions, police, and shipping companies, failed to achieve many of their goals due to Communist ineptitude, misuse, and abuse of funds, not political repression.

Additionally, peppered into Pedersen’s narrative are comments that paint only a partial picture—a picture devoid of context, a picture designed to reinforce his “orthodox” view. For example, we learn that the charismatic, soon-to-be leader of the International Longshore and Warehouseman’s Union (ILWU), Harry Bridges, “secretly joined the Communist Party.” While Bridges’ membership in the CPUSA is contested (he undoubtedly kept close contact with CPUSA leaders well into the 1960s), Pedersen does not illuminate us as to why Bridges may have wanted to keep his membership secret. Did it have anything to do with Red Squads? Was it because the shipping companies would have used it against him? Was he more effective as a trade union leader with his CPUSA membership left ambiguous? These are questions Pedersen fails to ask. Perhaps, they just don’t fit into his narrative.

During a discussion of the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike, Pedersen pulls on the anti-communist thread, even more, writing: “One of the cornerstones of his [CPUSA leader Sam Darcy’s] campaign to control the San Francisco ILA [International Longshoremen’s Association] was soft peddling the extent of Communist influence, beginning with the sleight of hand over funding and editorial control of the Waterfront Worker and including Harry Bridges’s concealment of his Party membership. Even championing the presence of Party members at rallies and meetings was a deception. The comrades at the rallies appeared as members of the staff of the Western Worker or under the camouflage of their particular organization: none were introduced as Communist Party members.”

Unfortunately, for students of history, Pedersen confuses more than he clarifies. Let’s briefly dissect the paragraph above: First, how the funding and editorial line of this or that publication becomes a “campaign to control” is altogether laughable. In effect, this line of argumentation boils down to: Workers are dupes, too stupid to analyze and assess information on their own. More importantly, did the workers themselves ask about the editorial line or funding of the Waterfront Worker? Did they care?

Is this in the historical record? Or did they instead welcome support wherever they could find it? Documenting how longshoremen felt about the publication would have been much more illuminating than Pedersen’s claim of a Communist “campaign to control” the union and the strike.

Second, Bridges was already an emerging and recognized leader of waterfront workers. His contested CPUSA membership is beside the point; he was loved and admired by the workers themselves and was chosen as their leader. Are the political affiliations of all union leaders up for public debate and scrutiny?

What about religious or community affiliations? Or are these personal matters protected by the Constitution? At best, this line of thinking leads to political registration (like those envisioned by Taft-Hartley and the Smith Act, for example) of people who hold unpopular political beliefs; at worst, they lead to detention camps.

Third, of course, organizations—political parties, grassroots groups, churches, etc.—want their members to appear at rallies and meetings, to help shape and mold an agenda. All political organizations have an agenda. That their leaders wear different hats at different times isn’t “deception.” It’s Politics 101.

Pedersen’s political naiveté is embarrassing.

The book concludes with a discussion of the birth of the East Coast National Maritime Union and the alliance between CPUSA leader Ferdinand Smith and the more conservative Joseph Curran, who would by the late 1940s/early 1950s betray Smith and the Communists.

Unfortunately, in The Communist Party on the American Waterfront, too often anti-communism, rumor, and hearsay pass as history. The anti-communist historian John Earl Haynes notes that Pedersen’s book “will be the definitive study of the subject.” While there are useful tidbits of information in Pedersen’s book, I couldn’t disagree with Haynes more.

The Communist Party on the American Waterfront: Revolution, Reform, and the Quest for Power

By Vernon L. Pedersen

Lexington Books, 2020, 205 pp.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

Afghanistan’s socialist years: The promising future killed off by U.S. imperialism

Communist Karol Cariola elected president of Chile’s legislature

Comments