LOS ANGELES— The Chinese Wall (Die Chinesische Mauer), written by Swiss playwright Max Frisch (1911-91) in 1946, entered theatre history as the first, or certainly among the first theatre works to address the entirely new issue of the possibility, now in the nuclear age, of global extinction. Coming so soon after the defeat of fascism, it also served to slam all manner of authoritarian rule.

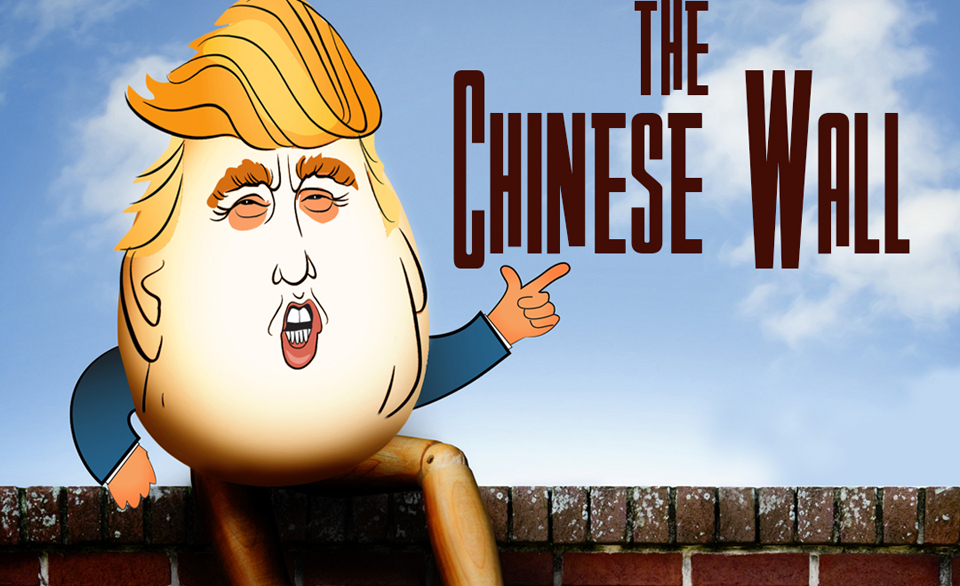

The Group Rep opens their 44th consecutive season with this play, translated by James. L. Rosenberg, and directed by Larry Eisenberg. In equal parts tragedy, comedy, history, and satire, this unpredictable “happening” bears close parallels to today’s headlines, with sharp digs at the Trump administration.

The official Seven Wonders of the Ancient World are all Mediterranean- and Fertile Crescent-situated, so they do not include the Great Wall of China, whose “completion” was celebrated in the year 220 BCE under the first Chinese Emperor Tzhin Zhe Huang Ti, called “The Son of Heaven.” In fact, little of what he built still survives, but the Great Wall has been rebuilt, maintained, and enhanced over various dynasties. Most of what we see today dates from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). It is certainly a marvel of world heritage, visited by millions of visitors to China.

The Great Wall is long enough to reach from New York to Berlin. What sort of emperor would delight in a protective wall preserving the integrity of Chinese culture and keeping Mongols and other “barbarians” out? And knowing something of this wall’s history, it’s apparent that its completion became little short of a national obsession for almost two thousand years!

And yet the very phrase “Chinese wall” has come to signify the futility of building barriers strong and high enough to bar unwanted people and influences. Today it’s just a tourist site.

Walls tend to be like that. Making it easy fodder for contemporary comment. As director Larry Eisenberg says, “On the day Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, The Chinese Wall immediately jumped into my brain. The parallels are obvious: An obsessive, megalomaniacal narcissist pandering to nativist xenophobia, who thinks that shutting out, shutting down and shutting up whole segments of the world’s population is a reasonable method for securing a nation, fits exactly the description of Max Frisch’s Chinese Emperor.…

“[It’s] a very precise lens for magnifying and ridiculing those bozos who currently lead our country. It is also a warning. When you have morons brandishing nuclear buttons and using them to compare dicks, it provides endless entertainment and chuckling around the water cooler, but it is also a warning that [the world] may very well be on the brink of total annihilation.”

So, “what is the play’s message?” asks theatre blogger Don Grigware.

“You can’t solve the problems of the 21st century,” Eisenberg replies, “using methods that became obsolete in the third century AD.”

The Chinese Wall takes place in the Emperor’s court in Nanking, ostensibly in 220 BCE. But Frisch has cast his play with both historical and literary figures from many different eras, such as Cleopatra, Brutus (Caesar’s assassin), Pontius Pilate, Romeo and Juliet, Columbus, Philip II of Spain, Don Juan, and Napoleon. They all have something to say about history and life, empires and emperors of the future. There’s also an academic historian simply called “Contemporary,” who Jimmy Stewart-like both observes the raucous goings-on and inserts himself into the action. The Chinese Emperor is dressed like a buffoonish Donald Trump, and Cleopatra of old morphs into the Melania of new, outfitted with the requisite pout, model’s swagger, and a sexy Central European accent. Ivanka and Jared stand-ins waver in their favor for Trump.

A character named Min Ko never appears but he is the specter that haunts the Emperor’s every waking hour—a man called “The Voice of the People,” whose verses the populace are following with heightened attention as the terror of tyranny mounts in the land. He is, of course, the “enemy of the people,” the “lying press.”

The show (seen Jan. 28) features some 20 performers (alas, too numerous to name individually), some playing multiple roles, and sumptuous costumes for all the historical characters. Video projections fill out the story and supply running commentary. Clips of Marx Brothers movies underscore the absurd humor, and contemporary songs about changing times fill out the soundtrack. The set décor tends toward the funky, with movable, multifunctional units. It runs almost two hours, with one intermission.

The production is, as I’ve tried to indicate, timely and admirably well intentioned. Like the IWW’s Little Red Book of songs, it aims to “fan the flames of discontent” with wit and righteous anger, and move a mute audience toward action. Yet integrating the crazy-quilt of characters into a Julius Caesar-type of story already laden down with obvious and somewhat repetitive satire, was a challenge this version of the play does not fully meet. All these unnaturalistic roles are difficult to imbue with feeling. Much of the humor is forced and heavy, the acting stiff and flat.

A video interview with director Larry Eisenberg and assistant director and cast member Todd Andrew Ball can be viewed here.

The Chinese Wall plays Fri. and Sat. at 8:00 p.m., and Sun. at 2:00 p.m. through March 11. Talk-back Sundays are Feb. 11 and 25 after the performance. The Lonny Chapman Theatre is located at 10900 Burbank Boulevard, North Hollywood 91601. For tickets and information see the website or call (818) 763-5990.

Comments