As the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic descended upon the U.S. in mid-March, the head of the nation’s most powerful oil and gas industry group wrote to President Trump. The American Petroleum Institute CEO, Michael Sommers, asked for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to exempt his industry from so-called routine reporting and monitoring requirements, a set of rules that form the backbone of federal environmental law.

Six days later, Sommers’ wish came true: The EPA announced a temporary enforcement policy stating that facilities — like coal plants, refineries, and wastewater processing plants — that weren’t able to monitor and report emissions of toxic pollutants during the pandemic would be excused. The agency “[did] not expect to” pursue fines when these facilities failed to fulfill their obligation to report the quantities of various cancer-causing chemicals they were releasing into the air and water.

In the following weeks, environmental groups and a coalition of nine states filed three separate lawsuits, arguing that the policy was too broad and essentially allowed polluters to decide whether or not they wanted to comply with environmental laws. Ultimately, despite the threat of COVID-19 showing few signs of slowing, the EPA phased out its policy at the end of August. But for 172 days, in the middle of a global pandemic, the nation’s top environmental cop looked to many like it was essentially off the beat.

“EPA’s COVID-19 enforcement policy was just ill-conceived from the beginning,” said Joel Mintz, a professor of law emeritus at Nova Southeastern University in Florida and former EPA enforcement attorney. “Whether intentionally or not, it sent a signal to regulated companies and to states that EPA was basically suspending enforcement during the pandemic. That was how it was perceived.”

Six months after the agency announced its temporary enforcement policy, a picture of its effects is slowly beginning to emerge. Self-reported data from industrial polluters collected by the EPA shows that these facilities conducted 40 percent fewer emission tests at smokestacks in March and April this year compared to the same period last year. Also, while only 325 facilities notified the EPA that they would be unable to submit water quality reports as required during those two months, more than 16,500 facilities simply did not submit them — that’s the fourth-highest amount of noncompliance in the last 20 years, according to an analysis of the agency’s own data.

In addition, reporters with the Associated Press calculated that state environmental agencies following the EPA’s lead granted more than 3,000 waivers exempting companies from having to comply with state-level environmental rules. The dearth of emission and water quality reports makes it difficult for both regulators and public watchdogs to determine exactly how much the facilities have polluted since March. For those who live near these facilities, it complicates efforts to hold polluters accountable.

Separately, a study by researchers at American University in Washington, D.C., found that counties with six or more facilities required to report toxic emissions to the EPA saw a 14 percent increase in particulate matter pollution after the EPA announced its enforcement policy. The study, which has undergone one round of peer review but not yet been published, also links the additional pollution to an increase in deaths from the novel coronavirus in these counties. On average, these counties saw a 53 percent increase in cases and a 10 percent increase in deaths after the rollback, compared to those with fewer polluting facilities. The study, which has received little attention, is the first to document what its authors say is a causal relationship between the EPA’s policy shift and an increase in both COVID-19 cases — air pollution weakens the immune system — and deaths.

Many of these findings complement Grist’s own reporting, which has found that the Texas state environmental agency pursued 40 percent fewer violations during the pandemic compared to the same period last year and that Pennsylvania’s state regulator conducted 37 percent fewer inspections following its coronavirus shutdown in mid-March. Many states also continued to permit oil and gas drilling at a normal pace even as they scaled back inspections and other enforcement activity.

EPA’s policy “opened the door to the wholesale waivers that many states granted, even to recidivist polluters in a number of cases, which was particularly disturbing,” Mintz said. Still, even as researchers and journalists piece together the effects of the EPA’s enforcement policy across the country with the limited data available, the true extent of the damage may never be known, he said.

“There’s no way to really know exactly what happened,” he said. “The government is not aware if there’s no self-monitoring of the incidences and volume of waste that are going out through leaks, and the companies very likely don’t know if they’re not monitoring.”

Disentangling the data

For most of her career, Claudia Persico has been interested in the effects that pollution has on public health, from causing kids to perform worse on academic tests to damaging the health of unborn children. A professor of applied public policy at American University in Washington, D.C., she has become intimately familiar with two EPA data sets: the Toxic Release Inventory and the Air Quality System. The former provides an accounting of the toxic pollutants that industrial facilities release and the latter contains information about air quality collected by thousands of air monitors across the country.

Persico thought of the two datasets in March when the EPA announced that it would be lenient when assessing fines for noncompliance with reporting requirements. Would the data show that the policy resulted in more pollution — and more COVID-19 deaths? After all, COVID-19 is a respiratory disease, and decades of research show that air pollution worsens asthma and other lung diseases. It also inhibits the body’s defense system, making people more susceptible to infectious diseases. A study published earlier this year by Harvard’s school of public health found that people who lived in counties with poor air quality were more likely to die from COVID-19. Even one microgram of additional particulate matter pollution per cubic meter of air could increase death rates by 8 percent, they found. A new study published last week in Environmental Research Letters, an academic journal, also found that counties with higher levels of certain hazardous air pollutants had a 9 percent higher death rate from COVID-19 than those with lower levels.

But Persico faced several challenges when she assessed the EPA’s data. For one, the toxics database only contains pollution information from factories that use certain chemicals considered especially dangerous by the EPA. Nitrogen oxide emissions, for instance, aren’t reported in the database even though they can cause asthma attacks and difficulty breathing. As for the air quality data, monitors are few and far between. Some counties do not have any monitors, and research has shown that monitors are often strategically placed by local regulators in areas with good air quality.

Then there’s the question of causality: How would the researchers know if facilities started polluting more because of the new lack of consequences or because of some other pandemic-related reason? It was a crucial question because companies were making the argument that key employees working on environmental and safety compliance might catch the virus, leaving them short-staffed and therefore unable to prevent pollution.

The findings, however, indicated that the date of the rollback was a turning point in the 2020 data. When the researchers looked at air quality data in 2017, 2018, and 2019, comparing counties with six or more facilities that reported emissions to the EPA to those with one to five such facilities over the month of March, they didn’t find any major differences in the amount of pollution. But when they ran the same analysis for 2020, they found that counties with six or more facilities had 14 percent more particulate matter and 5 percent more ozone after the March 26 enforcement rollback.

When the researchers then looked at COVID-19 cases and deaths, they found that counties with six or more polluting facilities also had a 10 percent increase in their daily death rate after the rollback. According to the researchers, deaths began increasing “substantially” six days after the rollback announcement, suggesting that “pollution affected deaths, at least in the short term, by causing existing COVID-19 cases to worsen.”

“In the absence of this rollback, there would’ve been fewer cases and deaths,” said Persico.

Persico found even more evidence that the increase in pollution was tied to the rollback when she looked at the polluting facilities’ compliance history. Counties where pollution increased after the rollback had more facilities that the EPA had previously tagged as “high priority violators” than those whose pollution remained relatively constant.

“When you minimize penalties and signal that you’re unlikely to fine [polluting companies], it might induce more facilities to emit more pollution, irrespective of whether or not the pandemic is making it hard on them,” said Persico.

The first version of Persico’s study was rejected by a journal after peer reviewers raised questions about the causality she attributed to the rollback. It was possible, they said, that legitimate challenges to maintaining compliance — such as sick workers — could have caused the increased pollution, rather than companies taking advantage of the rollback. In order to address that concern, Persico eliminated counties that had reported COVID-19 cases prior to the rollback from her study. That way, the increase in pollution wouldn’t likely be explained by workers contracting the virus in significant numbers. Even after controlling the data in this way, the results showed similar levels of increased pollution after the rollback, suggesting her original conclusions about causality were sound. She has since resubmitted the working paper to another economics journal for publication.

Mintz, the emeritus professor at Nova Southeastern University, said there’s “no reason to doubt the results” given that the researchers are “respected” and “their methodology seems to be sound.” He said the findings were “significant” but that he wasn’t surprised by them.

Seth Shonkoff, executive director of the nonprofit Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers for Healthy Energy and a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, said the study had a “relatively strong design” and that the authors “did a good job of controlling for other factors which could have gotten in the way.” Shonkoff pointed out that the study’s use of air monitors, which are designed to pick up on pollutants at the regional level, could have missed localized effects and actually underestimated the effects of pollution on COVID-19 cases and deaths.

“They used the best available data that they could have had access to,” he said.

Persico’s work complements research by data analysts at the Environmental Data Governance Initiative, a network formed after the 2016 election out of fear that crucial environmental data collected by the federal government might be deleted or altered. An analysis conducted by geography and geospatial sciences professors and data engineers, which was published by the network last month, also found that compliance with federal reporting requirements under the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act decreased after the rollback, with thousands of facilities failing to submit reports specifying the quantity of chemicals being released into the air and water.

Of the facilities that didn’t report smokestack emissions to the EPA after the rollback, 20 percent were noncompliant with the Clean Air Act for all of the last three years, and a third had been noncompliant for at least half that time. Kelsey Breseman, a data engineer with the network and a co-author of the report, said that the pattern of noncompliance suggests that serial polluters took advantage of the rollback.

“Even if they were to return to ‘normal reporting levels,’ I would have a pretty deep fear for all the communities that are impacted by this,” she said. “You can see serious health impacts years and years down the line, and I fear deeply that the people who are impacted will never be able to prove who caused that problem, and the burden will rest on their shoulders.”

Molly Block, a spokesperson for the EPA, said in a written statement that there is “no support” in Persico’s research to make the claim that the enforcement policy led to an increase in pollution.

As for the Environmental Data Governance Initiative’s report, Block said the work had not been peer-reviewed and claimed that the group has made mistakes when evaluating EPA data in the past. (The group did once acknowledge inadvertently undercounting EPA enforcement actions in an analysis of 2018 data.) She said the agency has initiated more than 100 criminal enforcement cases and 460 civil enforcement cases between mid-March and the end of July.

“EPA has not curtailed its enforcement during this public health emergency,” she told Grist. “Given that companies have had five months to adjust their operations to constraints arising from the pandemic, the agency expects that they have the experience necessary to comply with the regulations.”

“As always, if noncompliance occurs, EPA will be reasonable when deciding what enforcement response is appropriate,” she added.

Suit after suit

When the EPA first announced its relaxed enforcement policy, it said the measure was “temporary” but did not include an end date. After two lawsuits, led by the Natural Resources Defense Council and the state of New York, were filed against it, the agency announced in June that it would phase out the policy. A third lawsuit by the Center for Biological Diversity and other conservation groups was filed in August.

The attorneys general of nine states claimed that the EPA’s pandemic policy forced states to expand their enforcement capacity to fill the void left by the federal agency’s rollback. In New York, for instance, the EPA is responsible for enforcing water quality standards for wastewater discharges into rivers and streams. If the EPA reduced reporting requirements for industrial polluters, the state environmental agency would be forced to step in to conduct their own inspections and pursue violations. Last week, the state voluntarily dismissed its lawsuit after the agency confirmed that it had phased out the policy.

Similarly, a group of environmental nonprofits led by the Natural Resources Defense Council requested that the agency publish an emergency rule requiring companies that took advantage of the enforcement policy to provide written notice that they were doing so. When the EPA did not respond to the request, the groups sued, claiming that the policy created a “serious and immediate risk” and that the agency had delayed responding to their petition for an emergency rule. A federal judge ruled in July that the groups did not have standing because they did not establish the harm caused by EPA’s failure to respond to their petition. An attorney for the group said that they did not plan to appeal the decision.

The third lawsuit, however, will proceed. Last month, the Center for Biological Diversity and two other conservation groups filed a suit arguing that the agency had failed to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service — as the Endangered Species Act requires — to determine the effect the policy may have on vulnerable species. Jared Margolis, an attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, said that the EPA’s responsibility to consult with other agencies is still an issue even though the policy has been rescinded.

“It’s separate and aside from life of policy itself,” he said. “Just because the policy isn’t around doesn’t mean the health effects aren’t. People want to know what has occurred.”

Even though the EPA phased out its pandemic enforcement policy on August 31, the fight to ensure environmental laws are continuously enforced is not over yet. For one, the recent curtailment of enforcement during the pandemic comes at the tail end of decades of dwindling enforcement, according to environmental advocates and researchers. A 2018 report by the Environmental Data Governance Initiative found that civil cases against polluters that year fell to their lowest point since 1994. 2018 was also the second-lowest year on record for criminal cases, and the dollar amount of civil penalties collected dropped to its lowest level since 1987.

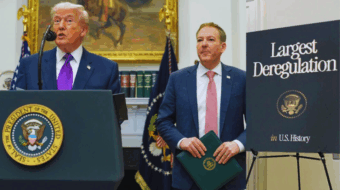

The Trump administration is now seeking new steps to provide regulatory relief to businesses. On August 31 — the day the EPA phased out its enforcement policy — the White House sent a memo to federal agencies directing them to take certain deregulatory steps in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, like dialing back enforcement when companies demonstrate a good-faith effort to comply with laws and increasing the standard of evidence when an agency wants to issue fines. While the exact result of this policy on the EPA is unclear, it could mean the agency’s willingness to hold polluters accountable continues to slide.

Margolis, the Center for Biological Diversity attorney, said that the EPA’s enforcement rollback “set a bad precedent.”

“We need to send a message that those who care about wildlife and public health shouldn’t tolerate this kind of behavior,” he said.

This article was reposted from Grist.org.